Pre-war Croydon Childhood 1928-1939

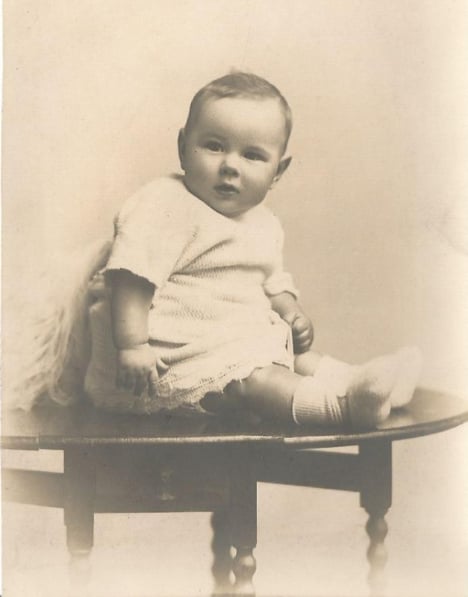

Perhaps this was taken next door at Mr Lay's photographic studio.

In 1988-90, Geoffrey wrote down what he could remember of his early life in a series of little stories. We begin at the beginning, with his early childhood in pre-war Croydon, then go through his life on the other pages, in pictures, recollections and documents.

Geoff, as he was known then, was the youngest son of Master Builder. They were a solid working class family. His brother and sister were much older, so he was brought up as an only child.

He later went to grammar school, to university and became a psychologist; catapulated into in a middle class world far removed from his own upbringing. He always considered himself to be working class, different from middle class people, even when living a very middle class lifestyle. You can take the boy out of Croydon, but you can't take Croydon out of the boy, sort of thing.

The family lived first at 13 Northcote Road, then moved to number 25, where various combinations of the family remained for over 50 years.

His own words are in itallics...

Northcote Road

Number 13 was in the middle of a terrace. Number 25 was at the end of a terrace, which was better for my father's building business. We moved when I was two and a half years old. I went along while it was being prepared - the kitchen range taken out and a tiled surround put in. There was a lot of mess. Dad did a lot of that kind of conversion before the war. Foresight would have been a great thing. We could have started out own reclamation business with all the ranges and fireplaces taken out, though we couldn't have stored them during the war, as they would have gone the way of the railings.

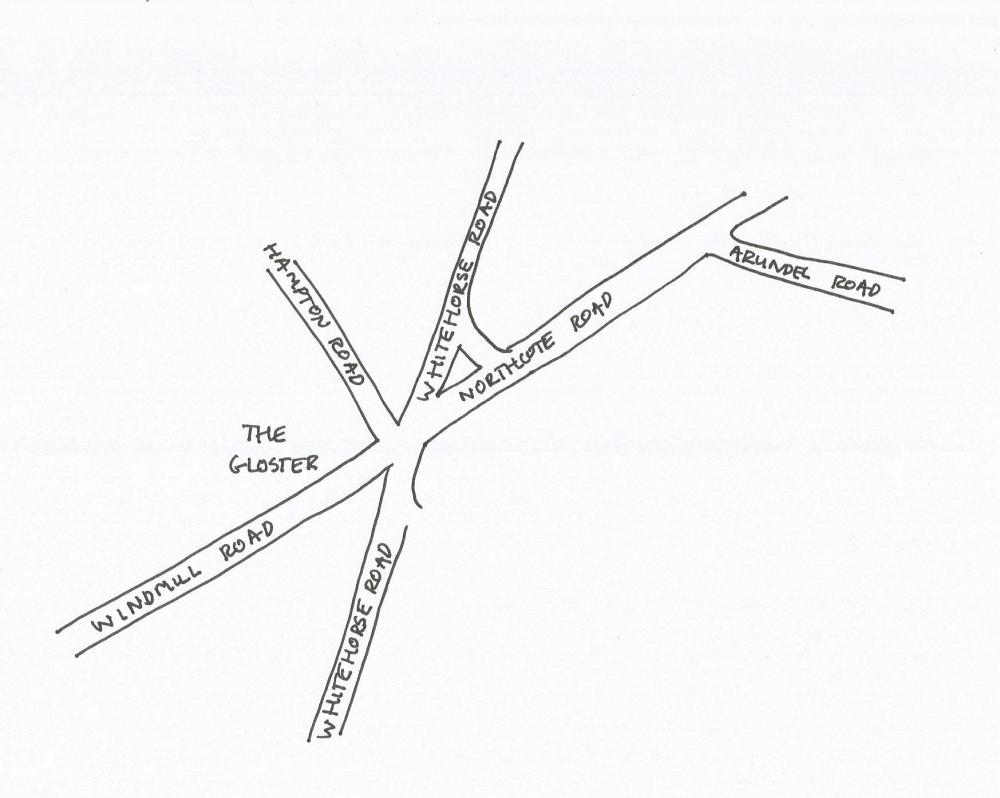

Northcote Road met Whitehorse Road at a narrow angle. The junction was known as The Gloster after the pub on the opposite corner. The triangle between Whitehorse Road and Northcote Roads was taken up by gardens for the first fifty yards, after which it was wide enough for the triangular plot which held the Isted's house and garden, down the dip.

It was a long time before I realised that the Isted's name was spelt like that. I thought we were leaving the H out of Histed. Access to this plot was through a twelve foot gap in the terrace. Number 25 adjoined the passage, opposite Number 23.

Tugela Road

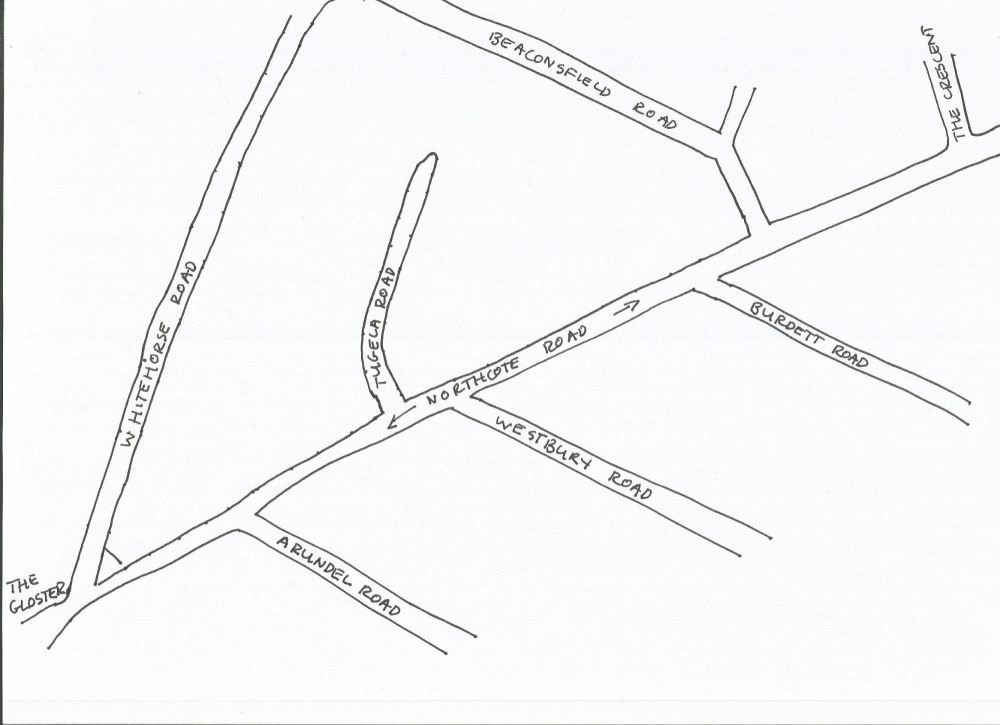

Another 25 yards up the road there was a side turning, Tugela Road, which didn't run all the way across the triangle, but bent round parallel to Whitehorse and abbutted the builders yard in Whitehorse Road. The roofing contractor's yard in Tugela Road, Adlards, occupied the remaining bit of the triangle, adjoining the Isteds'. I don't know why the Isteds were down a dip. The yard wasn't so there was a high wall and fence between them.

The wall ran right round the Isteds, and on our side of it ran the path to the backs of the gardens. The other gardens had back gates onto the path, but we didn't, as we had access to the Passage at the side of the house.

Next door, across the passage, lived Mr Lay. He was a photographer, and had a studio in his back garden, and a doorway on to the passage. He was not young, and retired at some time during my childhood. There was activity earlier. He was a dapper man, and wore stiff collars. His studio was a marvel. He had great big plate cameras, with brass fittings. There were lights on stands. I think it was during the war that he died. In his demeanour, and his mode of occupation, he was almost a representative of the last century.

Daisy and Reg Arnold

The Arnolds, Reg and Daisy, were brother and sister. They lived four doors up. I spent many hours and days with Daisy Arnold when I was little. It was almost my other home, and I suppose I was almost the child she and Reg never had. I can't remember what Reg did for a living, but he wore a suit.

Geoff and Reg Arnold in the Arnolds' garden at Northcote Road, about 1931.

The Killeens lived round the corner in Tugela Road.I remember Mrs Killen. Her son was Dennis and he was a pianist. I still saw him around in the seventies when I went to stay that way. Mrs Killeen was a great buddy of my mother.

The Watsons lived in Tugela Road too. They used to come round in the evenings for whist. I could never get on with whist, although Mum and Dad taught me. The same ineptitude extended later to poker, and I never learned bridge. When the adults were playing whist, I used to sit at the top of the stairs and evesdrop. Sometimes I was allowed downstairs to see them for a while.

Most of the houses were late Victorian three up and three down, 1875 Housing Act houses. Whitehorse Road houses were bigger - an extra basement story with steps up to the front doors.

Sydenham Road School

Opposite, were Arundel Road, Westbury Road and Burdett Road. The school was at the other end of Westbury and Arundel Roads, running between the two. It was called Sydenham Road School, but lay behind the houses in Sydenham Road and had its main entrances in Westbury Road. It must have been a hundred and fifty yards I had to go to school.

Further up the road on our side, a road, Beaconsfield Road, did run through to Whitehorse Road, which provided a good long tricycle ride without crossing any roads. Even further up was The Crescent, in which was the grammar school I went to. That was a quarter of a mile away.

Toys

I think the farmyard came from a cousin, complete, which was lovely- horses, cows, pigs, sheep, people, fences, sheds. The lead soldiers, (like the farm animals) all lead, of course and a fort to go with them. The soldiers were built up bit by bit.

Then there was Meccano and the trains, which accompanied me into adolescence. The trains were O gauge, and clockwork. Little coaches of tinplate, buffers- and how pleased I was when I got one of the buffers with long pistons you could actually push in. They don't have these at Paddington on the real railway now. One Christmas I had a magnificent new engine. I remember the early light, and the shape of a box by the bed, and the wonderous joy upon opening it. Well it was nice, a Bassett-Lowke.

There was always difficulty about having the trains set up, as the track got in the way. Sometimes I had it set up on top of the shed. Fine if the weather was fine. I saw a big permanently set up train set when I was a child. It belonged to one of my cousins at Merton- my mother's brother's family.

Meccano allowed all sorts of things to be made. There were little bridges, wagons and cars, cranes. I think the best thing I made was a big crane, which could be turned on its base, and the lifting gear ran along a track. The thing I wanted to make, but never did, was the Forth Brige. I wanted at one time to be an engineer so that I could build the real Forth Bridge. Never designed a new type of bridge, either...(but he did build a super suspension bridge and box girder bridge on his model railway upstairs in our family home in Bath.)

Hornby O gauge trains, and Meccano, no longer exist. I sometimes wonder what my childhood toys would be worth now that they are collectors' items. I don't remember what happened to mine.

There were cars and other vehicles, not only Dinky toys, (lead of course, how did we survive?) but tinplate working models. An early toy was a tank, which sparked as you pushed it. It had rubber tracks which came right over the top, like the first tanks at Cambrai. A little later, just before the war when I was about nine or so, I had a racing car made by Schuco. A Mercedes, all silver with a steering wheel which turned the front wheels, and a differential on the back axle. It really was a beautiful toy, like the Mercedes itself, a bit of a Third Reich display.

Earlier, there was a teddy bear. A very nice teddy bear, not big, but with soft long fur, and real-looking eyes. Had him for years.

Reading

I liked reading when I was quite small, and read a lot- more than I do now. There were comics, of course, Beano, Rover and Film Fun. Some of these began in my time, I think. Greyfriars Annuals were a great standby, and there were story books which didn't only turn up when I was ill, but also, I remember, from visits to Dad's sisters Ada and Jessie, 'the girls', although they were in their fifties.

Some of these were collections of adventure stories, which I liked, but which I now recall as being extraordinarily racist and imperialist. The heroes were young, white and healthy, sometimes deceived for a while by the deceitful republican conspirators until they were put right by the wronged royals, or they were in the African or South American jungle, battling against rebellious and cruel Natives and nasty Portugese who mistreated the Good Natives. Great stuff. I doubt if you could get away with publishing that sort of stuff now.

I read Shakespeare. Sounds odd for somebody of nine or ten, but we had got a complete Shakespeare through the Daily Express, which was the paper we always had. I read a lot of the plays, and at least got the gist of the stories.

A great favourite was Everybody's Enquire Within, which came in weekly parts, for years, it seemed, and which we then had bound by the publishers. It was wonderful when the sets of magazines came back as pristine books, which of course I still have, and use.(As do I now, ed.) Shakespeare and this, were what made me 'good at general knowledge'.

Illness

I had the usual crop of childhood illnesses for the time; chicken pox, measles, mumps, croup, whooping cough, scarlet fever, and something supposed to be meningitis but which probably wasn't. Most of them kept me in bed at home, though scarlet fever took me to the isolation hospital at Waddon Marsh. I went to hospital, to the Sydenham Hospital, to have my tonsils out.

My memories of the hospitals are scanty, but I do remember the immediate preparation for the tonsil operation, the operation table which was hard and cold, and the anaesthetic tank. There are vague uncomfortable memories of the hospital, being dumped on a bed presumably when I was coming to. I must have been in the isolation hospital for a longer period, by comparison. There were visits, and a locker by the side of the bed, and so on. The ambulance, which I must have seen on later occasions, was a dark blue, quite different from the usual cream ones.

Being ill at home was different. I was on my own in bed, and in my own room after Elsie was married and away from home. Before that I shared with Arthur, and before that, when I was quite small, my bed was in my parents' room.

Illness meant two things. When the fever was high, there was misery, and very, very long lonely nights. When the worst had passed, there was a mixture of boredom, and a wish for company, and the enjoyment of a certain amount of indulgence. Different food- Bovril and little fingers of toast, bread and milk, and lemon barley water, or best, homemade lemonade. At some time, Mum and Dad would come in from shopping, and come up with a present- a book or a toy.

Whooping cough was early and horrible. I had croup too- or was it the same thing? I don't think so. There were inhalations to do, with a towel over the head, crouching over a bowl of steamy water with horrid smelly stuff in. I hated that.

It was the 'suspected meningitis', which probably wasn't which took me to a convalescent home. That was in Herne Bay, which was run by the Boy Scouts. I was a cub at the time. This was in 1937 as far as I can remember. It was an impressive time, and I have all sorts of memories. The house was a large one, Edwardian perhaps, with a large garden. In the garden was a pond. In the pond were terrapins, which fascinated me. I also learnt about calceolarias. There was a lot of Scout stuff. It was, I suppose, run like a scout camp. Some of the lads weren't too well. There was one who was often in pain. I think he'd lost a leg. I had a particular friend, who was from Hackney. Very impressive that, because of the Hackney Scout Song Book. We had quizzes and I always did well, because of the amount of reading I'd done. I had a camera with me and I still have one or two photographs.

At home, our doctor for years was Dr Murphy. His surgery was round in The Crescent. There was a lot of talk about The Panel before the war. Dr Killian was our doctor when Dad died in 1948.

Household objects

The telephone. The first one I remember, stood like its successors on the left hand end of the sideboard. It, the telephone, was one of the stick kind, with an earpiece hanging on a hook on the right hand side. There was no dial. To make a call you lifted the earpiece and wiggled the hook until the operator said 'Number please?' You had to give your number too. 'Thornton Heath 1354'.

It was replaced with one which had a great big dial on the base. That was exciting, and modern. It was inscribed with our number and with the injunction to dial 999 in case of emergency. This happened some time before the war, but I don't recall when. The flat kind with the one piece hand set came along much later.

Cleaners. There always seemed to be a Goblin, yet I seem to recall a new one arriving. It was a cylinder, dark grey in colour covered with a sort of leathercloth. The end pieces were chromium. This cleaner went on for years and years. Presumably it wasn't possible to buy a new one during the war.

The Ewbank was the manual carpet cleaner, and it too went on for years, accompanying my childhood.

Uncut Moquette. The new three piece suite came just before the war, in uncut moquette. Seemed important, the uncut moquette. It consisted of little loops, quite stiff, which gave a detailed and interesting texture. It was pretty hard wearing, although these pieces got tatty by the seventies.

The dining room table. Dad cut the corners off, and made them round although the quarter circle was ofset a little so there was a rebate on the short side. He did this because I banged my head. I must have been about table height. Never saw another table like that.

Washing clothes. The kitchen sink was a big china one. Just like the one we have in our house now. It was used for washing up, and for clothes washing. The clothes were boiled in the copper, or boiled then scrubbed in the zinc bath which was filled from the copper and lifted, by my mother, onto the kitchen table. They were wrung partly by hand then through the hand mangle into the kitchen sink for rinsing. The mangle had rubber rollers and a large handle. It was clamped on the edge of the sink. I've a dim recollection of a mangle with big wooden rollers too.

The Week

It used to start on a Sunday although the weekend was important as a unity. Sunday was quite different, though. We didn't go to church, and it wasn't a religious day. What was special was Sunday dinner, mid-day. Roast beef, sirloin sometimes. It went in the oven mid morning and smelt good. The batter for the Yorkshire pudding, Croydon style, went under the roast to catch the drips, or at least, some of them. There was enough fat to make the dripping, which provided bread and dripping later in the week, with salt.

The conventional roast, Yorkshire pudding, roast potatoes, also under the roast, and vegetables, provided more than one meal. We had some cold meat for supper, although there was a good deal of picking done during the afternoon. Monday dinner (mid-day) was cold meat. Tuesday or Wednesday Shepherd's pie. Bubble and squeak used up the vegetables with the cold meat. Fish on Friday, usually cod, sometimes skate.

We used to eat dinner (mid-day) as a family, with Mum and Dad, Arthur when he came to work with Dad, though not Elsie, as she ate in work. For supper (tea) we had some hot dish like egg or Welsh rarebit, or seafood as well as bread and butter and cake. What they call High Tea in the North, but we had it too.

Tea on Saturday was more special. We used to go to the football at the Crystal Palace during the season- Dad and me. Did Arthur come? Sometimes one of Dad's friends would, I think. As I have said to my family before now, we used to order crab on the way up at the fishmongers in Selhurst Road, and pick it up dressed on the way back. For tea there were winkles, and shrimps, bread and butter and jam, jelly and blancmange, in that order. Winkles involved pins, and games with the lids. Dad put them on the tips of his fingers, and made them appear and disappear. Fly away Peter, fly away Paul.

That wasn't the end of Saturday, either. We would settle to listen to the wireless and eat sweets. Dad used to buy a pound of boiled sweets in town, at Maynards, usually. Rows of big bottles. Saturday night had 'In Town Tonight' at seven and 'Music Hall' at eight. In winter, round the fire, it got quite hot, on the front at least. Going out into the kitchen for food was cold. Shut the door. Going out to the lavatory was colder, and usually necessary. I didn't mind the cold so much then. It was quite refreshing in more ways than one.

Sunday nights on the wireless had 'Sunday Night at Seven', which later became 'Sunday Night at Eight'.They had to alter the jingle or signature tune.'SUNday night at SEVEN'S on the AIR', became 'SUNday night at EIGHT is on the AIR'. That was a secular programme of course. Richard Goolden did his character of the old night watchman sitting by his brazier. Yes I wasn't very old before that became giggle-worthy.

Richard Goolden was in many Children's Hour plays. There were some good ones, like the Castle of England series- history. I listened to Children's Hour regularly, it was on late enough to hear when I came in after school. Toy Town was a regular favourite, and I can hear Larry the Lamb's voice now. It was Uncle Mac of course. "Be good, but not so very good that one of the grown-ups says 'and now what mischief have you been up to?'"

There were of course the weekends when we went out on the motorbike. Summer for that. I'm sure it was on a Sunday, but I can't work out what happened to Sunday dinner. We may have gone out after it.

The Shed

The shed, or The Shed, was important. It adjoined the house, and ran the full length of the garden, originally, although it was altered later. The old shed had sliding doors to the passage, the gap in the terrace of houses which gave access to the house 'down the dip' where the Isteds lived.

The passage, apart from giving access to the shed, also provided the side door, which Dad cut in the wall through what was a cupboard in the dining room. The cupboard became The Lobby.

The sliding doors in the first part of the shed opened into a double width garage, though it was not called a garage. It held the motor-bike combination, and the Truck - a builder's hand cart with big wheels, holding about 4'6" x 3'6" x1'.

The garage part of the shed was separated from the main part, by a sort of corridor across the width, with a door both ends, one to the passage and one to the garden. The entrance to the longer part of the shed was from the middle of this passage. There were benches and shelves along each side, and a passage down the centre.

The Shed, about 1931.

In it were all sorts of wonders. 56lb weights, things for soldering (lead pipes, of course), tools, pipes, steps, rings, ropes, bottles, tins, blocks and tackles, gutter pipes (cast iron, of course), drain pipes (earthenware of course).

On top were more things. Large iron brackets for scaffolding, various long things. I got to go up on top as I got a bit bigger, and spent some time up there, too.

There was always sand available. I could make interesting branched tunnels with rainwater pipes, and pop balls in to see where they would come out.

The Swing

There was a swing. It was big, built by my father with 3x6" beams. It was about 8 foot high, and the seat was solid wood, the ropes about 3/4". I spent hours swinging on it. It was alongside the shed, and when it swung high, I could come up to a level of the shed roof.

Swinging was a sort of relief. Fed up, annoyed, miserable? Have a swing. It was also a sort of power; moving fast, flying, swooping. It played out some phantasies of being able to fly, sweep away, to look back.

Deliveries

There was a representative of a paint firm who called now and again. He left me a model ladder once. White lead paint lasts, the blurb said.

Mr Clark rode an upright bicycle with an enclosed chain. A Rudge. He called every week to collect the premium for the Liverpool and Victoria. Penny a week, Mum said, for the funeral.

Bread was delivered to the door, as well as milk. The same milkman came for years and years. What was his name?

Coal was delivered, or rather sold from the coal cart, horse drawn. The men were black with coal dust and wore hats with leather skirts over their shoulders. I have an idea of them coming through the house and dumping the coal in the coal cellar which led off the scullery, as did the pantry.

There were lots of horses, one way or another. People popped out afterwards with their buckets and shovel for the gardens. We did too, sometimes.

Ice cream was sold from tricycles, both Walls and Eldorado. The preferred one was Walls. I know I sought that rather then Eldorado, but I don't know that the ice cream was any better.

Sometimes there were bands- six or eight men in a row, walking along the gutter and playing. Mum made a distinction between German bands, which were alright for some reason, and unemployed bands, which weren't. It was questioning my mother's political decisions, like this one, as I got older, that were the beginnings of my turn to socialism.

"We should have a bathroom"...

The lavatory or WC was accessible from the outside, and was the third bit of the end of the house. That's as it was at least until the day when Dad said we should have a bathroom, fetched a sledgehammer from the shed and knocked down the wall separating the scullery from the larder and coal cellar. At some time, the scullery became the kitchen.

School

I must have begun infants school when I was still four. There weren't any play groups or nursery schools then, not round our way anyway. I went to Sunday School, at Spurgeon's Tabernacle, the Baptist Church which the Arnolds went to. I remember the room we met in, and a little illustrated book we used. Mum told me later that I used to say I didn't believe them when they said that Jesus could see what we were doing, because he couldn't see through walls. It's possible. Must have tickled Mum to think so anyway. I do remember the stories, Moses in the bulrushes, infant Jesus and all that stuff.

I was eager to get to infant's school, but it was a pretty awesome experience. I felt excited but sort of isolated in this big strange place with all sorts of big boys and girls (like six). In the baby class we had toys, and could bring our own. I took a golliwog and recall throwing it up in the air in the class and trying to catch it. I don't know if that was approved of or not.

We used to sit on forms- long bench seats. They were always being moved, it seems to me. There were times we sat on the floor in rings, but I don't know why. Later on we sat in bench seats. Now there was a time when we definitely had little slates and chalk to write our lines, but that must have been at the beginning when we were learning our letters. I knew them already, as I could read before I went to school. The Sunday School may have had something to do with that. The slates had sort of staves of four lines, base, top of small letter, small riser, long riser and descenders, not that we called them that.

The main memory, at the infants and at the juniors or Big Boys (there was a Big Girls too- all three in the same building) was of ink. Ink in ink-wells on the desk which demarcated each place; the ink in tin jugs from which the ink wells were filled by Ink Monitors; ink on pens dipped in the ink-wells and scratched on the exercise books; ink on fingers, trousers, handkerchiefs, faces. Not that it was the very strong dark ink. It was a wishy-washy blue-black, which wrote a sort of grey.

I used to take lunch, and go home to dinner. Lunch was two biscuits wrapped in grease proof paper, and eaten at morning break. I don't remember that there were any school dinners. Maybe that started during the war.

The infants school was mixed boys and girls, but the juniors were single sex. I think on the whole that I liked school. I certainly liked learning things, but there was anxiety too about the life. I was worried from time to time by rough boys, who did no more than taunt, really. Of the teachers I remember Miss Peace, a bit fierce. Mr Auchterlonie, pronounced Okterlonie, was young and had something to do with the trip we went on to Oban and Staffa and Iona. (The Highlands and Islands from Croydon as juniors in the 1930's? What a fantastic trip!)

Mr Eyles was our form teacher in the later years. He was considerate and interesting. I think I was a bit of a favourite. At least some rough boys said so. Once when Mr Eyles was demonstrating how to cut a nick in the top of a pencil so that one's name could be inscribed to avoid 'You've pinched my pencil!' squabbles, he showed one that he had prepared and written on the first name that came to mind- mine. Great embarrassment going up for it.

We had school camps as well as trips. The ground was at Caterham, a few miles away, in the country. Several of us went in a car of another of the teachers. It was a Ford V6. We knew about cars. We had visited the Ford factory after all. I didn't know anyone else with a car. Teacher's salaries couldn't have been bad then, could they? At the camp we did camp-like things; making fires, putting up tents, singing and going on walks. One of the teachers had a cine camera, and we saw the film later. Most odd seeing oneself. It made some sense of a comment on one of my reports about a tendency to boisterousness.

On one of the walks, through woods and fields, we came across a big house which seemed magical. Half-timbered, set back across lawns. I've never identified it, but I did draw it at the time. It sort of chimed with romantic fairy story and history notions.

We seemed to do a lot of plays, and they were fun. One was about Crusaders and Saracens. I was a Saracen and had a beautiful scimitar and shield made from plywood and painted silver, by my sister's husband. There was some reference to my trusty scimitar in the script. There were readings in class in English lessons, too. 'The Taming of the Shrew' I remember. I was Petruchio.

We had a white rat in a cage, in class. He was beautiful.

The piano teacher

Miss Lane taught piano. She taught me for years, I think some time before the war, then again after I was back in Croydon. I gave up when I was about fourteen, to concentrate on school. Miss Lane lived in Beaconsfield Road. She was a spinster, wore dark, even drab clothes, and was quite plain and proper. I think she graded what I did quite well, and was not a strict disciplinarian, in spite of her primness. I didn't learn to play very accurately, but she stuck it. She plainly loved the piano and music. We used to discuss the first concerts I ever went to, during the war when I was about thirteen or fourteen. These concerts were held at the Empire, the music hall in the High Street, or another hall or cinema. They seemed always to have an overture, a concerto and an interval, and a symphony. The concertos were mostly piano, with Solomon, Moiseiwitch or Eileen Joyce. Solomon was serene, Moiseiwitch intent and humourous and Eileen Joyce wore gorgeous dresses and got bouquets. Why don't men get bouquets?

[We have kept a Solomon record I found amongst Geoffrey's records when he died].

The shops and some of my friends

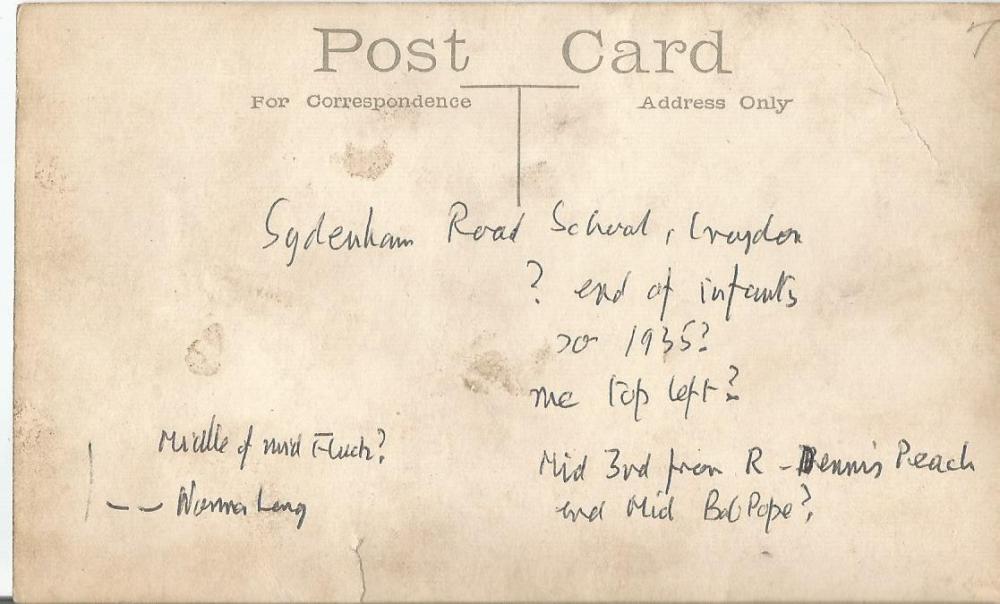

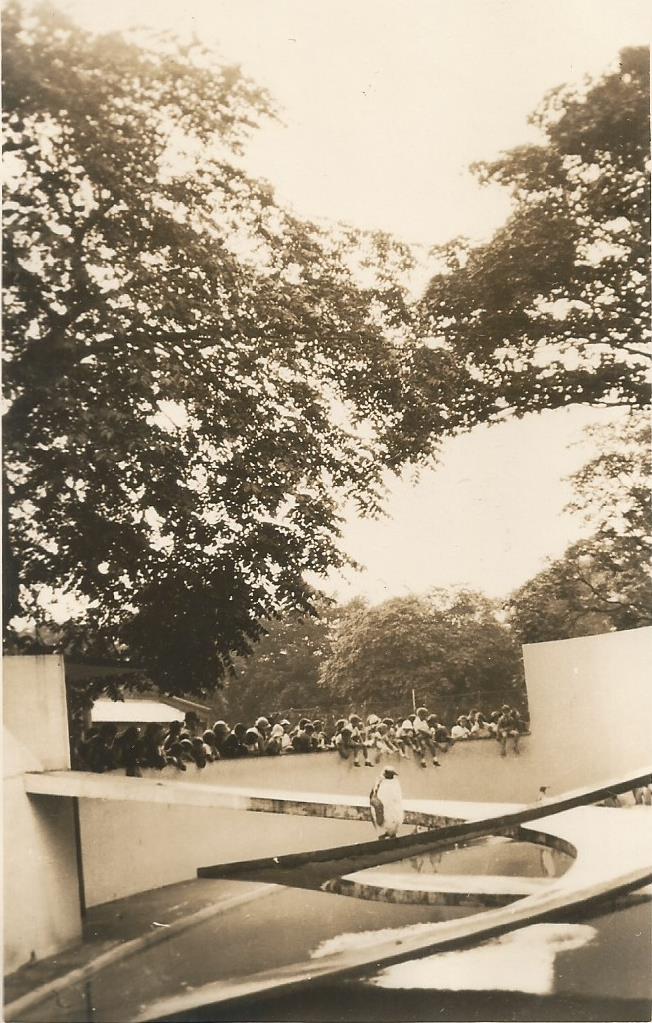

Sydenham Road Infants c1935. Geoff top left. The reverse with some names, below. Some of the boys were the sons of shop keepers mentioned in the next section.

At the Gloster, where Northcote and Whitehorse met, there was a newsagent and tobacconist and a cafe. There were just a few shops round the corner but most shops were the other side of the crossroads.

At the corner shop, newsagents and tobacconists, were the Lobbs. Tony Lobb and I played together a lot, mostly in his house. It was bigger, and they had a maid, Edith, and a film projector on which we could watch Mickey Mouse under the sink, and get in Edith's way. Tony Lobb went to Whitgift School, the local independent fee-paying school, and we lost contact. Education certainly separated us all.

Down the road where the shops were, lived Bobby Pope. His father ran a printing shop which was a source of prolonged fascination for me. I loved the trays of typeface, and to see them made up, and see the printed sheets emerge from the machine. It was all typeset, with quite small machinery. My father's business paper was done there of course. I lost contact with Bobby when we changed schools. I don't remember where he went, but he turned up on the telly as curator of entomology in the Natural History Museum.

I suppose most of my play at home was by myself, but I went out quite a lot. When I was small I had a red tricycle - one of the ones with a flat metal seat and pedals on the front wheels. It was succeeded by a tricycle with a chain drive, and with that, I always had transport, and that meant not only economy of effort, but legitimate independence. I used to tour the triangle of streets, and I was told later on, that I made a number of friends among households on the way, so that if I was missing, a walk around the block would show where I was by the trike outside. I remember the feel of it.

Days out

They didn't just stay in Croydon all the time. There were lots of visits out, days at the beach on Sundays...

Roly Truman, left and Geoff on Camber Sands, one Sunday afternoon in 1932/3.

and later Geoff had a camera and took his own pictures

Canterbury Cathedral Gate in 1937.

The Penguin Pool at London Zoo, in 1937, three years after it was built. It remained in use until 2011. I love the mass of children dangling over the edge.

Geoffrey continued...

A lot of play with friends was in the street, along the pavements, and round the corner in Tugela Road, which was a cul-de sac. There were Rough Boys too, who interferred and taunted, and were to be avoided.

Some of my friends were from the infants and junior schools, but others were just local. Bert Green from school remained local, but I lost touch with him when we went to different secondary schools at eleven. We met again when we were in our twenties and he opened a carpentry shop and workshop. We made the big loudspeaker which is still in my house, woofer, tweeter, modified Gately horn and all. Still playing, of course. We still exchange Chrismas cards.

Bert died in 2010, but their large corner speaker was the main speaker in our house during the 1960's and 70's and was in the dining room after that, connected up to the other room so that music could be played throughout. It was still working in 2015....so it outlived both of them.

Sydenham Road Juniors, 1939. Geoff middle row, second in from right with possibly Tony Lobb next to him. Bert Green is on the left end of the middle row.

Round Tugela, there were the Banks, who lived next to the roofing contractors of which Mr Banks was the foreman, I think. That is how we met Ronny and Tony Banks. Their house was interesting, as it had a tunnel through it, like a coaching inn, to give access to the yard. They went to a different secondary school, too. I think they and Bert Green went to John Ruskin, but I'm not sure.

The Luxor cinema

Over the road, the continuation of Northcote Road was Windmill Road. This was mainly foreign territory when I was little, except for the cinema, the Luxor, or fleapit. I used to go on Saturday rushes to see Tom Mix and such. Full of kids. Lot of noise. Must have been hell for the people who ran it. It was quite small, uneconomic you might say, compared to the big new ones going up in town - Davis for instance, or the Savoy, to which I was regularly taken by my parents. Cinema going was weekly, and started when I was quite little. I remember seeing films that were shown when I was seven or eight. The little Luxor wasn't favoured by my parents at all.

Right at the corner was the Surrey Timber Yard. I often went there with my father to pick up supplies. I loved the smell of newly sawn wood, and the corridors between stacks of seasoning wood. They used to season wood then.

Criminal streets

Further down Windmill remained strange for years. The first two turnings were Wilford and Forster Roads. Dad made some sort of point whenever he had work down there. He would usually mention it in some way that was different from the way he usually talked about where he had been working. He would tell me that the policemen always went down there in twos, but I came to suspect he was joking. Rough lot down there, but it was alright, decent enough people where he was working.

Much later, Terence Morris wrote a book on criminal areas and cited these streets as such. Well, well. One other contact was much later in my twenties, when one November night I followed some lads who had thrown fireworks at me and my wife Jean in our back garden. They met up with a group of lads one of whom while I was talking, coshed me with a sand cosh. I tottered home and we called the police, but they never said they caught the assailant. Must still have been a criminal street to some extent, though I canvassed those streets for elections in the forties and fifties without trouble- solid labour.

The shopkeepers at the doomed Glos'ter corner

Turning left at the Gloster, there were a couple of houses and a side road before the shops. A geengrocers was first, then set back was Goldsmith's the plumbers merchants and later Ralph's the glass merchants. Home and Colonial, then Martin's the butchers, the Dolly's hospital (important early on, that's where I got my pop-guns), the Victoria Wine, Nobby Clark the shoemender, an electrical shop and Pope's printing workshop. There were quite a few shops and some choice, two or more butchers, a Liptons and so on. Young Ralphs, Martins and Popes were at school with me.

The opposite side of the road began with the Gloster pub. It said Glo'ster on the roof. My father and brother never used it, so it was always somewhat alien. There were drunks around there from time to time. By the time I was old enough to think of trying it, it had gone.

Among the other shops along the same side were a delicatessen, which we didn't use either. Always seemed strange, with odd shaped sausages and cheeses. It seems now the sort of place to cultivate, with the tastes I and many others developed later. There must have been such people locally then. There was something about it, during the war. I don't know if the owner was interned as a German, or whether I just picked up some prejudice from my mother.

Among the shops we did use were the grocer, Scotts, which was long and thin, and had rows of biscuit barrels. Mr Scott was white haired and jolly. Butter was in a big slab, and a lump from it was shaped with wooden pats. Walloms the chemist was a double shop, with a very long counter, but not deep. That's where I was taken to be weighed, at first so I learned, in a basket scale, and later on the platform with the balance arm. The chemist, whose name I forget, as I don't think it was Wallom, had a thin face and big horn rimmed glasses, and gave me barley sugar sticks.

Obliteration

The pub, the cinema, all these adjoining shops, and most of the people, disappeared one night in the late summer of 1944 with one of the 141 flying bombs which landed on Croydon. It's funny, but during the war, especially during the air raids of 1941, I used to look out on the familiar view at the back of the house - the fence and shed of Adlards, the houses across in Whitehorse Road, and wonder if they would be there tomorrow. Air raids declined, and it wasn't until near the end that a part of the immediate locality disappeared. Quite a lot of damage was done to Croydon, which left gaps after it was cleared up. Trivial in comparison with what the developers did in the seventies.

On the next page, war and Selhurst Grammar School