Croydon in World War 2 | Evacuation to Brighton | Selhurst Grammar School for Boys

Grammar school boy, in his very smart Sunday best. Geoff aged 16 in 1944.

The first person in his family to go to grammar school

This page has documents from, or connected to, Selhurst Grammar School in Croydon and a host of other original documents from the 1940's. It also has Geoffrey's recollections of evacuation of his childhood in wartime, written in 1988. His words are in bold itallics.

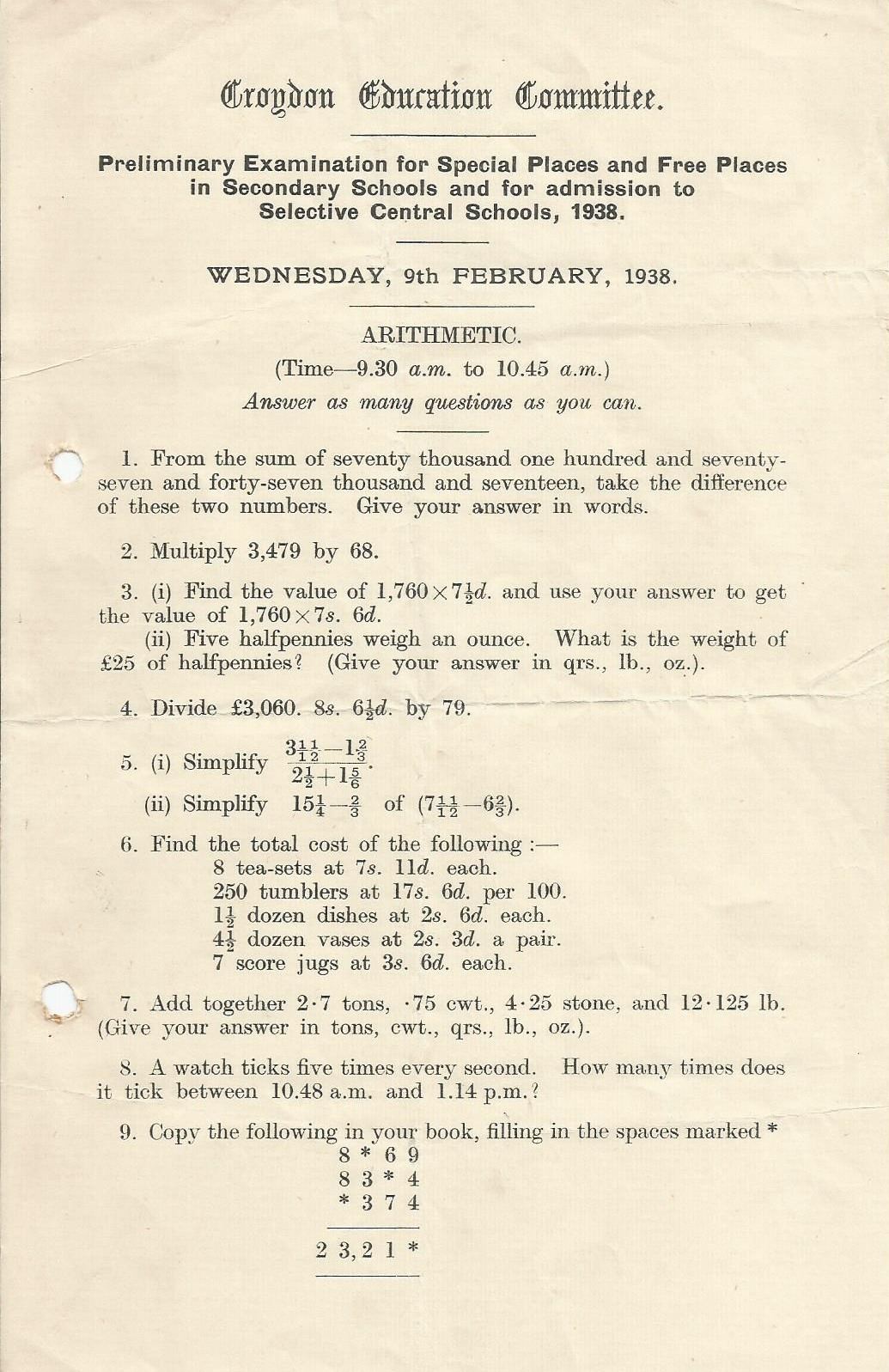

Geoff, as he was known in those days, was entered for the scholarship exams necessary to get a free place at grammar school. This in itself was an achievement for a working class boy in the 1930's. Geoffrey was lucky that his parents were older and well established and that he was the only child at home.

Grammar school cost money, in uniforms and sports kits etc, even if you got a scholarship. The lack of household income generated by those who stayed at school until eighteen meant that many working class boys who went to grammar school did not stay long.

This was pre-Eleven Plus, so only children whose parents could afford it, or were going for a scholarship, were entered for the tests.

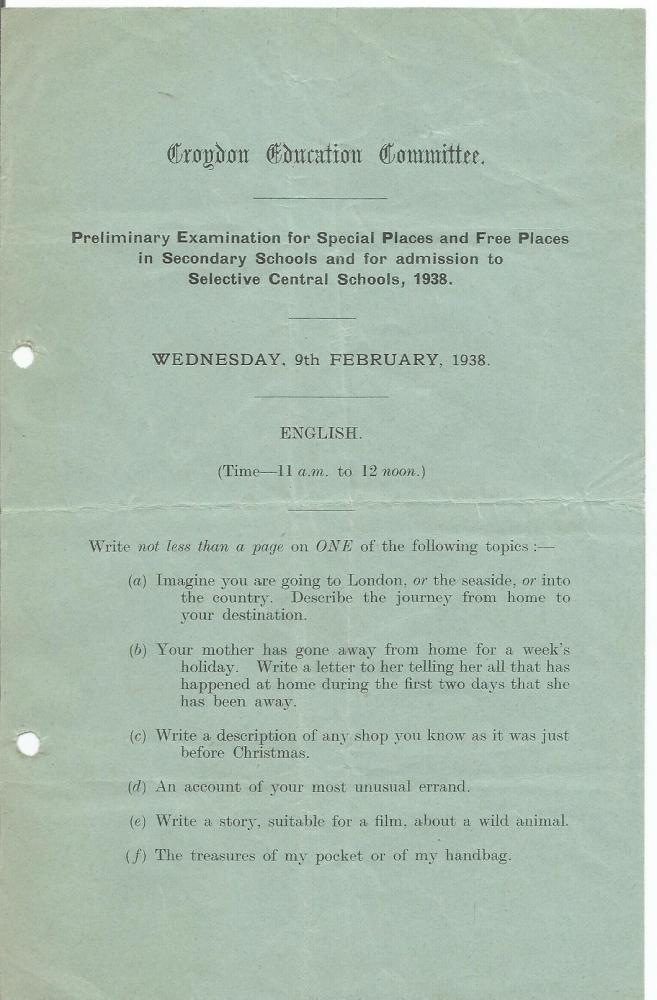

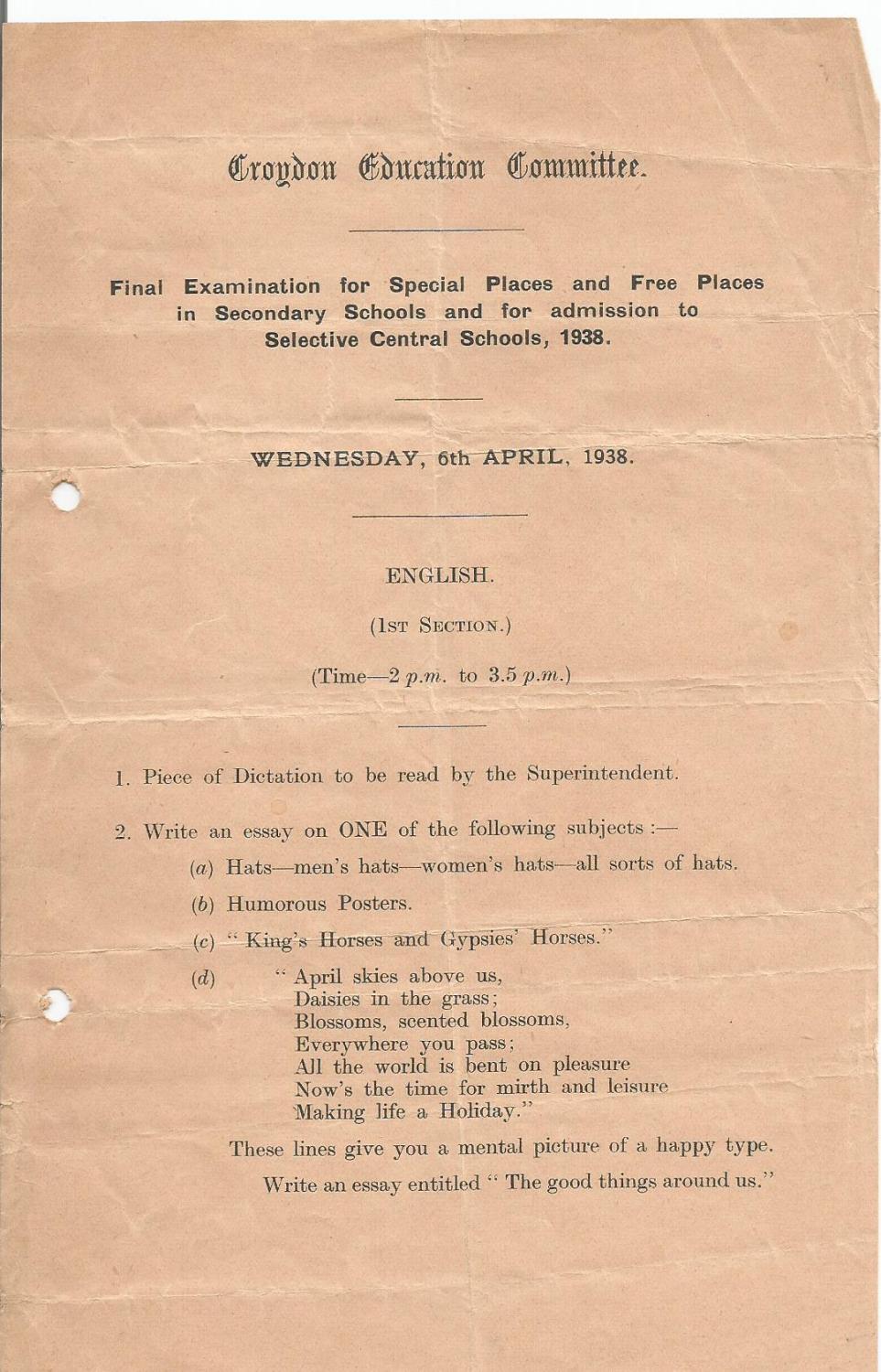

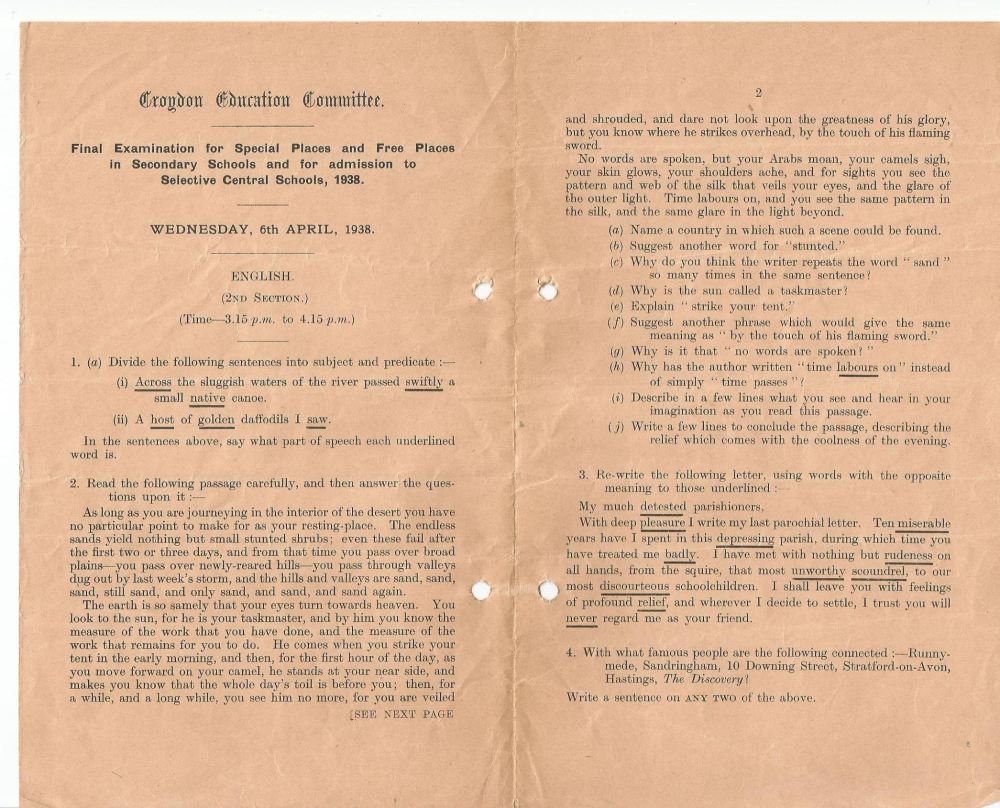

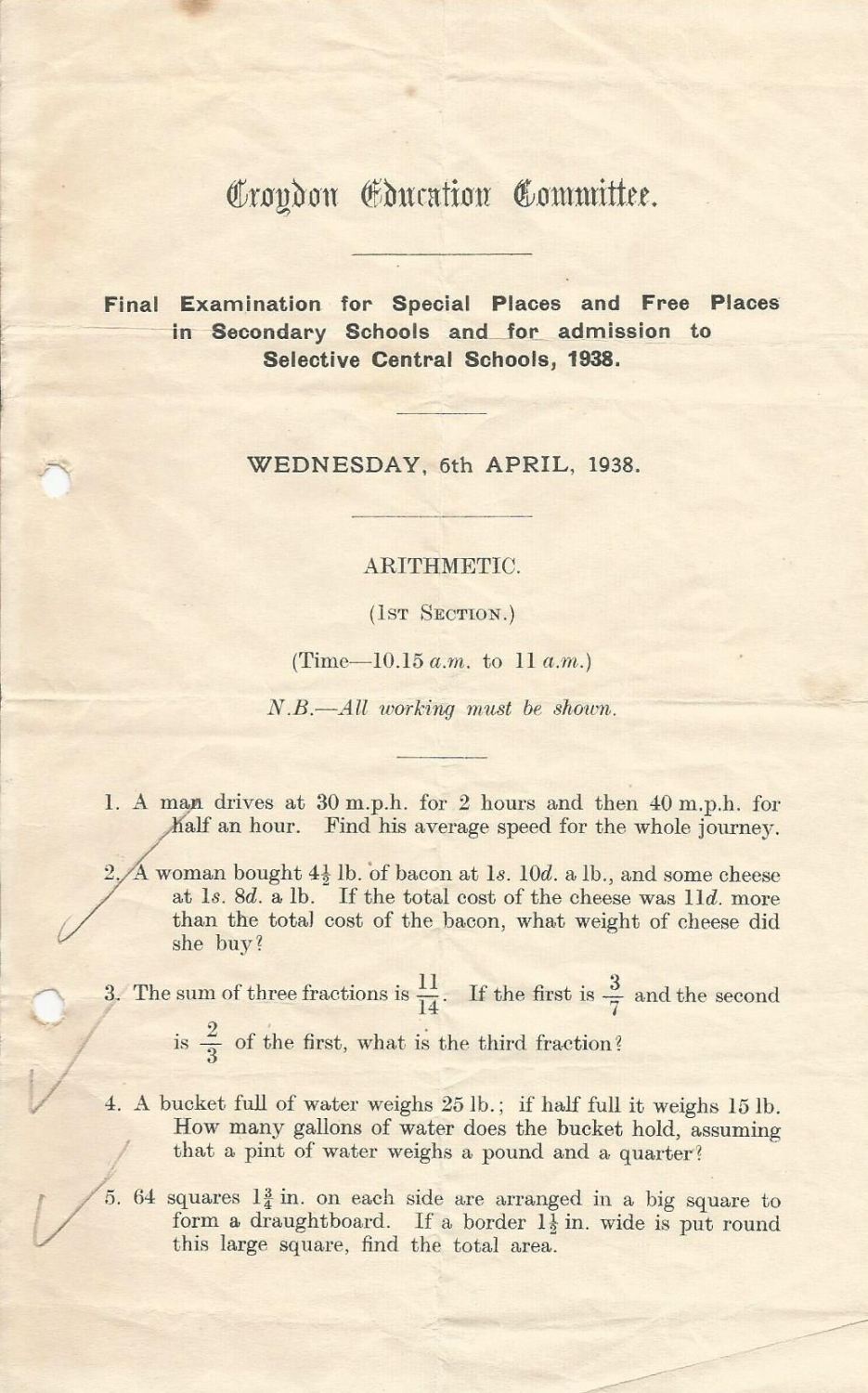

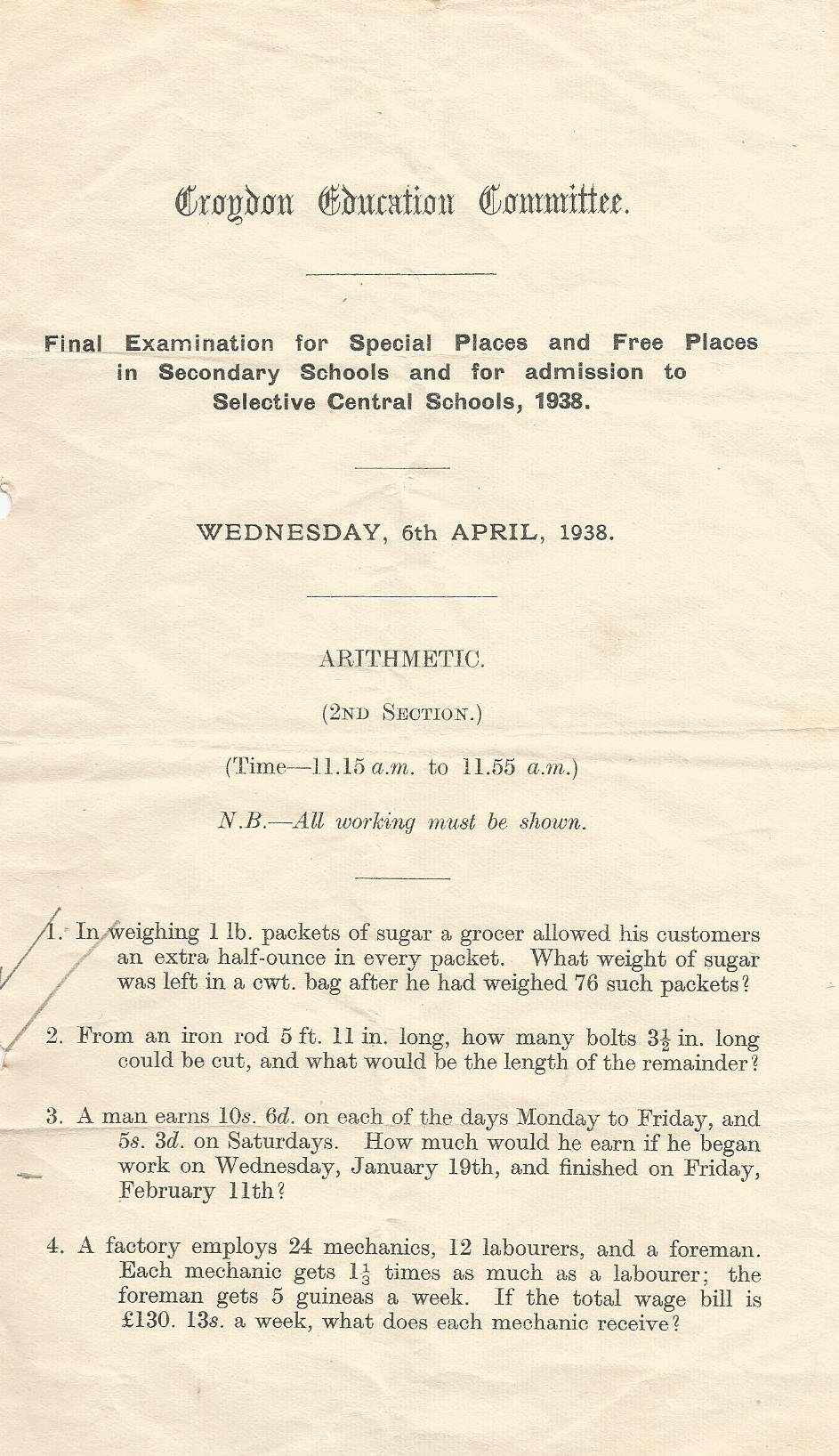

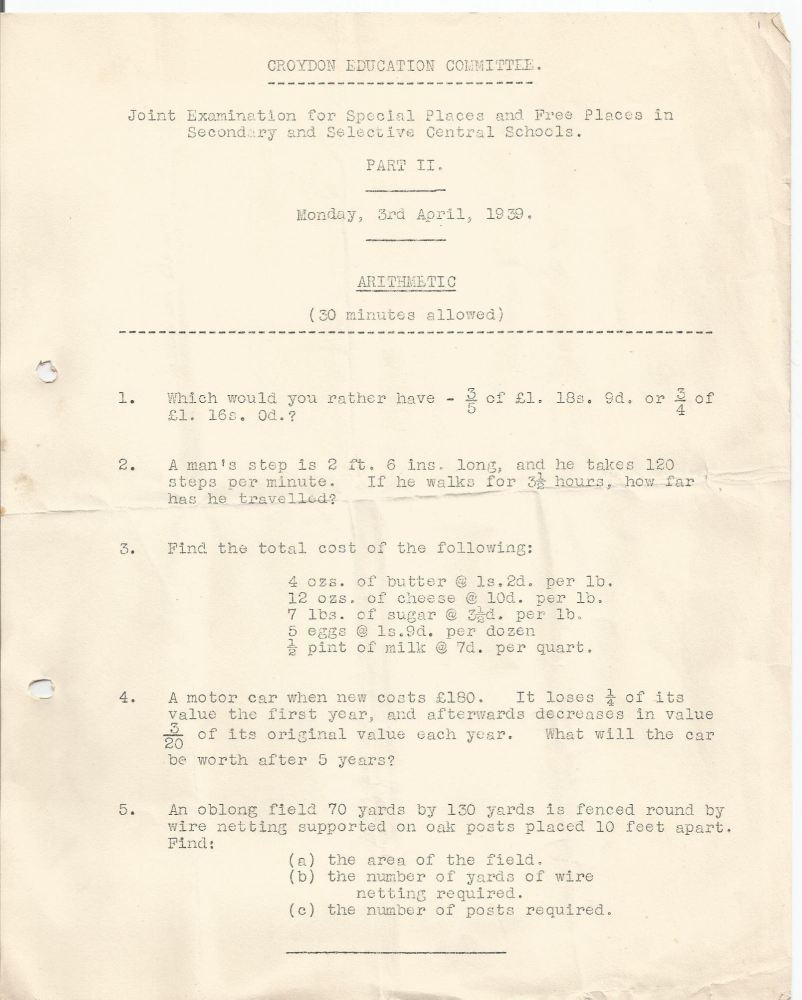

There was a battery of tests, which, for some reason he started taking a year early in 1938, when he was ten, failed and took again the next. The papers here range from February 1938 to April 1939.

I don't know how early the idea of going to Grammar school emerged. It came from the school, not from my parents. There was no family tradition of other than basic education. Both my siblings had gone to Tavistock Road Schools. There was explicit coaching for some of us. I remember the first scholarship exam, all very formal. There were questions I couldn't understand and couldn't do. There was a feeling of hopelessness, and it wasn't fair. There was a lot of excitement over winning the scholarship next time, though.

The Preliminary Examinations 1938

The Final Examination papers 1938

The Exam in April 1939

The surviving papers for 1939 are somewhat less impressively printed and it doesn't say whether this is a preliminary or final examination.

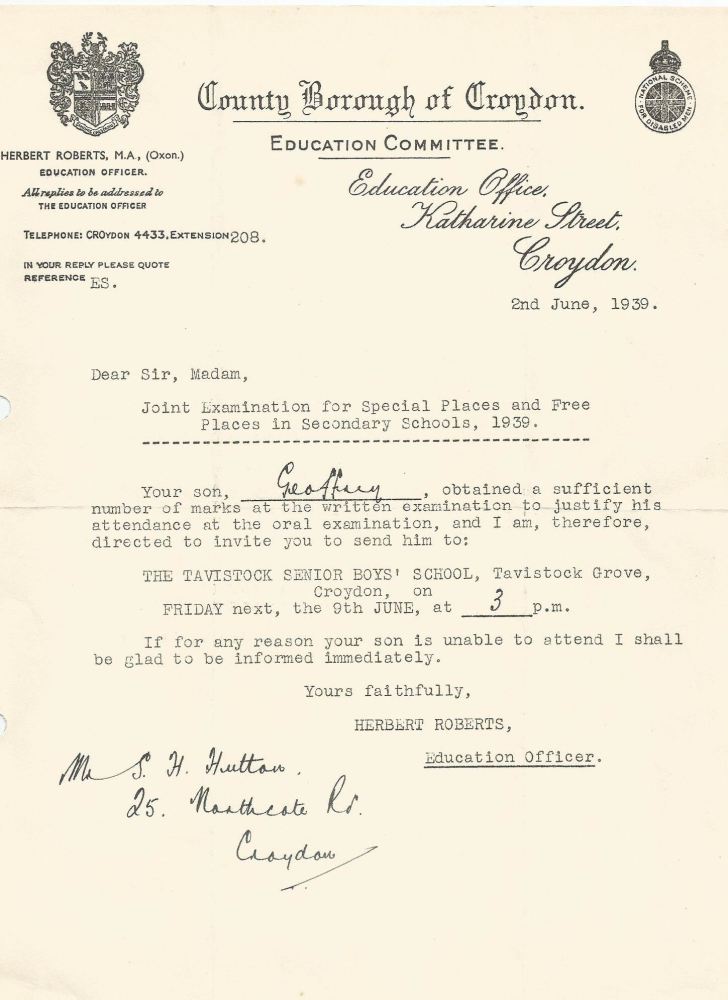

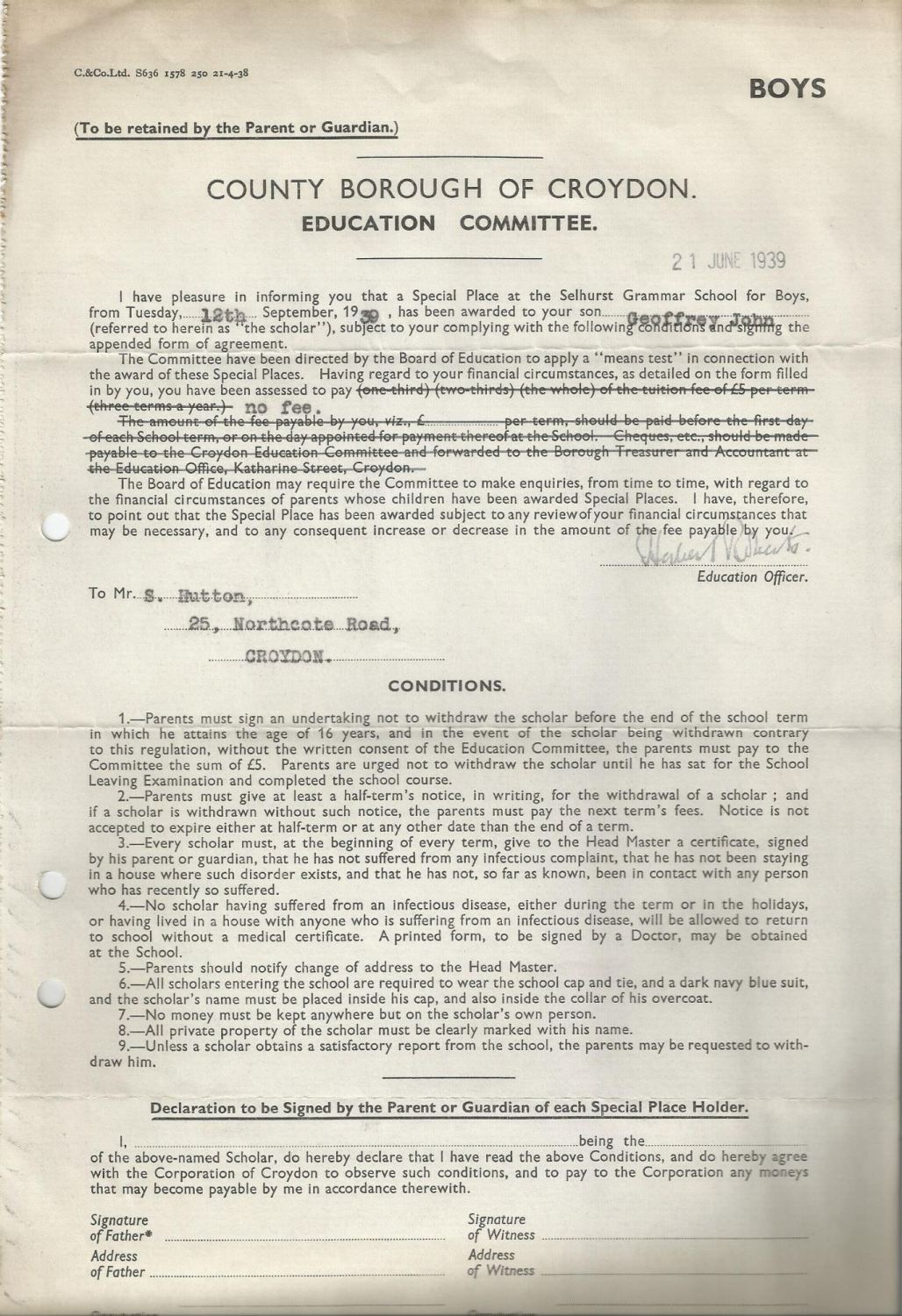

After doing this for two years and eventually passing, Geoff's dad Sydney Hutton received this letter, offering yet another test.

Passed!

After successfully completing all of this, he was awarded a place at Selhurst Grammar School for Boys. As he said, it was very exciting. It must have been a sensational feeling of success.

Letter of Acceptance and means testing

War. Evacuation to Brighton

Having duly turned up for the glorious first day of school in September 1939, they were immediately evacuated to Brighton.

I was in Brighton on holiday just before the war broke out.

Geoff's own photo, from his childhood album, of his mother, possibly on Brighton beach in 1939. It was undated.

This is the only photo I have ever seen of Nanny in middle age. I didn't know she had such dark hair, or that she wore glasses. Possibly she already had the galloping short sightedness that came with the beginning of the glaucoma. She was blind by the time I knew her. Having a blind grandmother seemed normal. Uncle Arthur eventually went blind, and it continues down the generatons. Seeing how Nanny coped makes it not too bad. We have something in common. Quite comforting really.

Geoff continues...I remember feeling something about the prospect of war, and what it could mean. We went back to Croydon, perhaps early, in the atmosphere of impending war.

We heard the broadcast of Neville Chamberlain " I have to tell you that no such communication has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany". It was a very strange feeling, something like an announcement of the end of all I knew about. My images of 'war' were clear and subsequently shown to be inappropriate. They had come from a wealth of stories, live and on the wireless, references in speech, the games we played as boys, Poppy Day and the two minutes silence- a hell of a long time, and all the traffic stopped. Mons, Ypres, Paschendael, Cambrai were all as familiar as Newcastle, Manchester, Bristol.

Brighton is where I went to begin my evacuation and this was a day or two after the main mass movement. I thought it was because Mum and I went home from holiday to find the school already gone, so followed them. My brother had joined the Territorials after Munich, as he didn't believe there would be peace in our time. He had also bought a Linguaphone German course, which fascinated me and which I dabbled in too, then and later. He had already been called up and was away from home; so I felt directly involved.

It was a new school for me, as well as going away from home, and it being war. My mother came down to Brighton to deliver me. I remember going to a first meeting of the school, so we were there in time for that. It turned out that it was a new school for the headmaster too. There was a meeting in the Hove Grammar School for Girls, at which the new head, F.W. Turner talked about his hopes for the school - 'I want this to be a school with no cane.' Good idea, I thought.

It all seemed fixed, where I would be staying. It was up at the back of Hove, just below the Downs, as it turned out. New houses, semi-detached, in crescents. Seemed quite posh to me. A young couple, though grown up like my sister, and brother. Childless as yet.

Probably Brighton, taken by Geoff, c1939.

He (I wonder what his first name was?) worked in his father's family firm. Brightons made sweets. Her father, Mr Peet, kept a pork butcher's shop and made pork pies. Marvellous. I became very fond of them and loved the visits to the sweet factory and the back of the butcher's shop.

They were quite indulgent, really, though Mr Brighton (always Mr and Mrs Brighton) had a nice way to caution me or to get me to do something different. A sit down talk, explanation of what was required and what they felt, a walk-over-with me. They wanted a bit more tidyness, or a bit of help in the house. It never occurred to me, as Mum didn't require it of me.

At Christmas, they bought me what I asked for, which was a toy model howitzer. I thought it was marvellous, and remember an occasion walking down the road with Mrs Brighton in her fur coat, holding on to her arm and saying how real the howitzer was, but not so that it would give any secrets away. Daft thing to say, which is maybe why I remember it. I still have it.

Geoffrey treasured the presents he got from the Brightons all of his life. We, his children, were never allowed to play with them, but he showed them to us proudly. We still have the howitzer.

The school didn't meet in the girl's school in Hove, but in the boys Brighton Grammar School. We worked shifts. Brighton Grammar went in the mornings from 8 to 1, and we went in the afternoons from 1-6. This gave us all the mornings free. It was winter in Brighton. Very different from summer in Brighton, which I knew. The family used to come down to Brighton on Sundays before the war. Dad had a 1100cc Royal Enfield. Dad drove, my brother rode pillion, my sister, before she was married, in the Dickie seat and Mum in the sidecar with me on her knee. We overtook cars on Pease Pottage. We went to Black Rock, Rottingdean, Littlehampton, Camber Sands. I knew Old Stein and the beach railway. I didn't know the back end of Hove, nor the downs, nor Portslade.

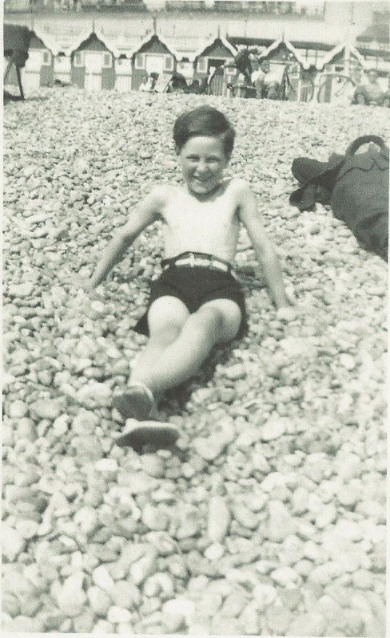

A young Geoff on a beach, somewhere on the South Coast, a few years before the war. My grandfather, his father, is sunbathing in his Sunday best; three piece suit and hat.

Those school mornings, and the weekends were full of exploration. I didn't used to feel the cold then, so snow was no trouble. The downs were beautiful. The beaches, deserted, wild, with colours of grey. There was the town too, or rather both towns.

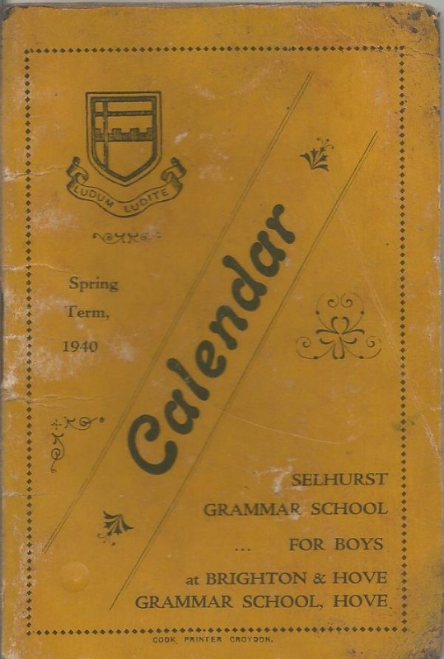

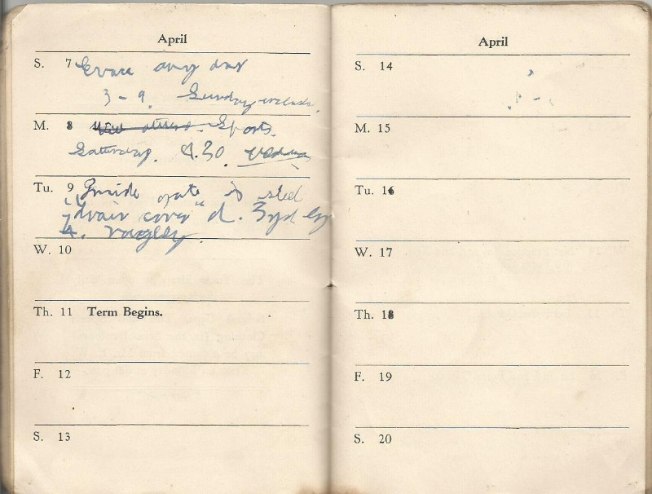

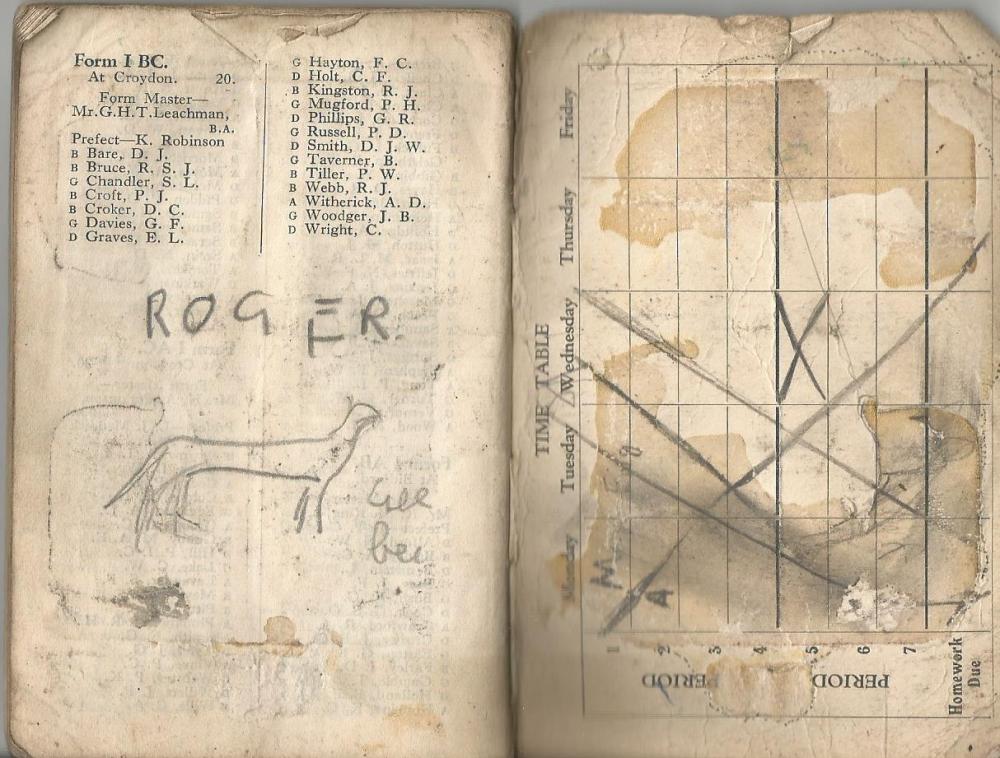

I used to go about with friends from school, but there was a girl too. She was evacuated, but from a different school. She lived in the next crescent down, and we took to going up in the downs together. Sounded funny - going up in the downs. We had favourite patches, one of which was a hedge which must have been eight or ten feet through, and had a sort of clearing in it, in which we played houses. I spent a lot of time with her, and I remember feelings of joy and something of awe. But I can't remember her name. She went away. She was more or less my first girlfriend. After writing this, I later found a School Calendar for Spring 1940. In it, in another hand, was written 'Vicki, 8 Brook Road' and a little map.

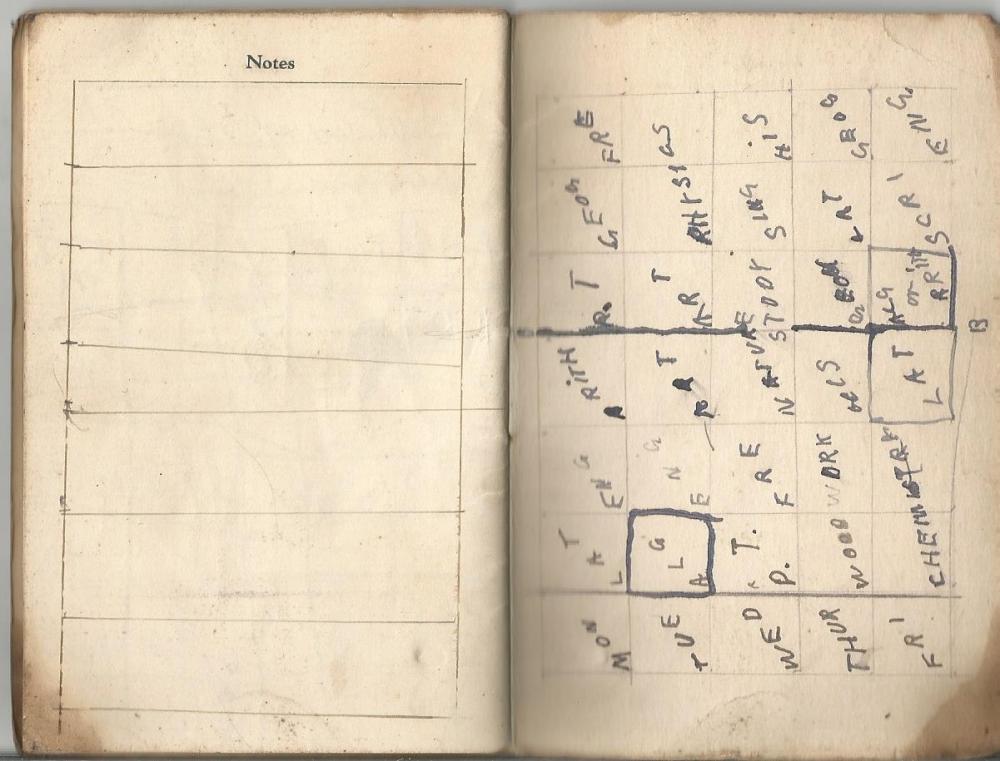

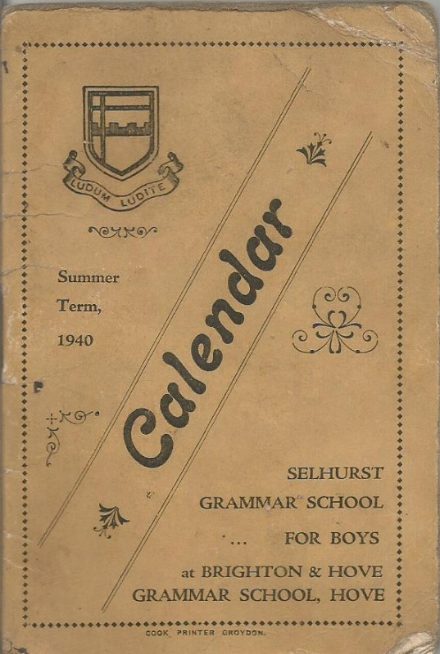

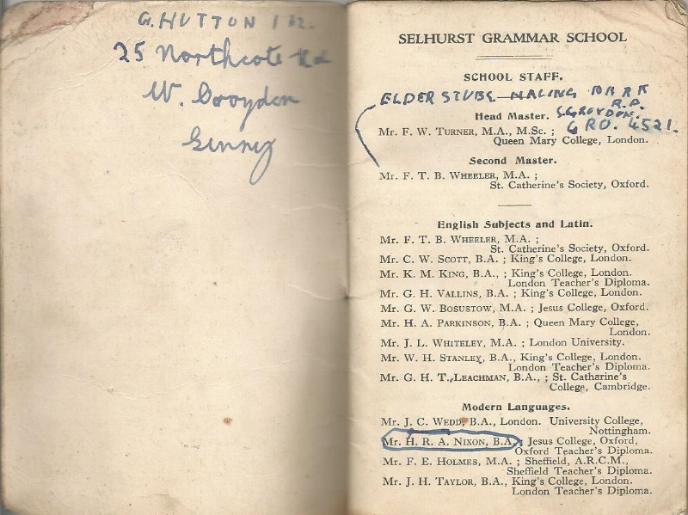

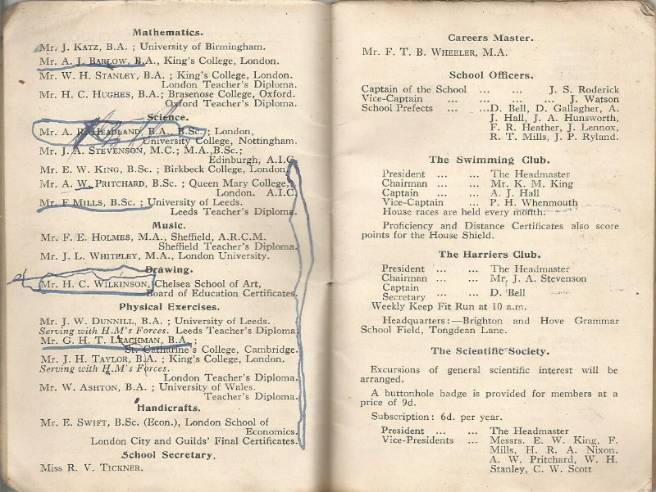

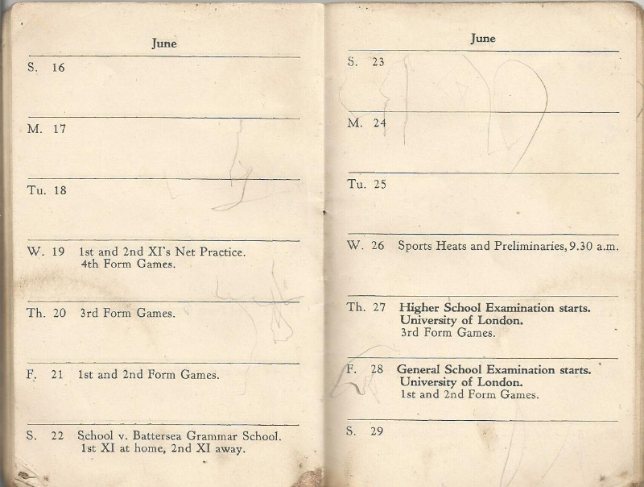

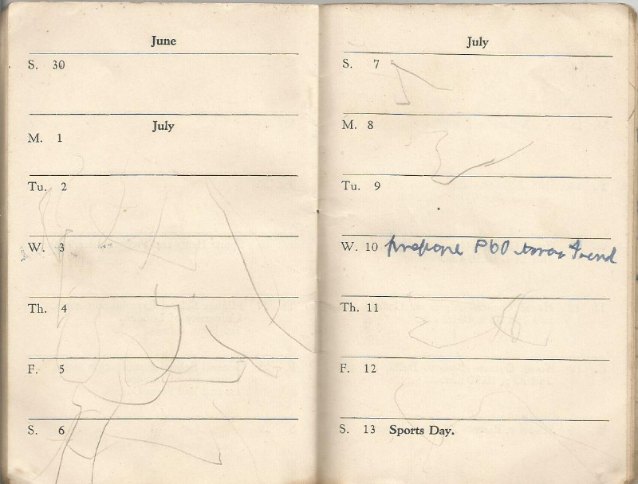

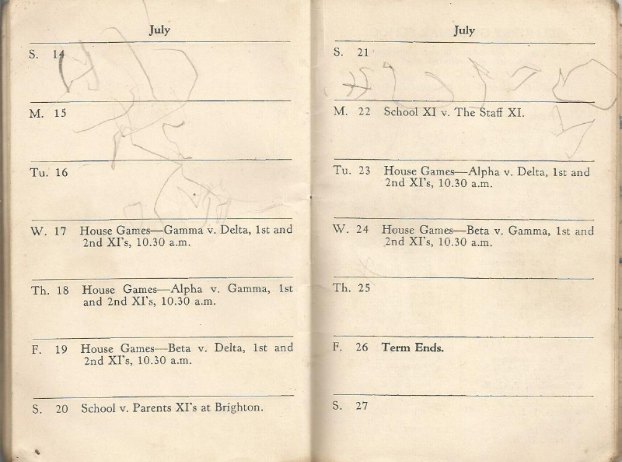

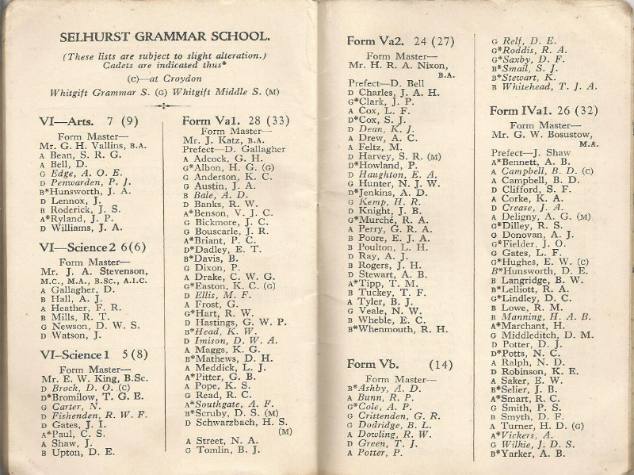

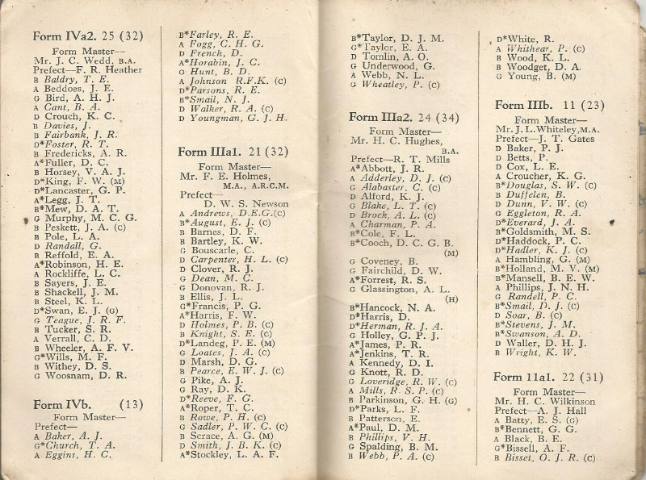

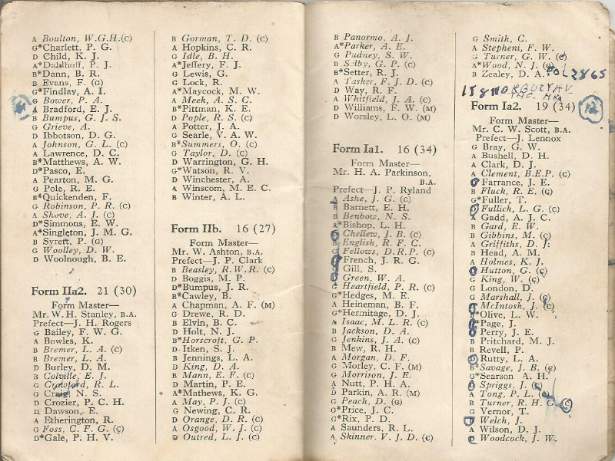

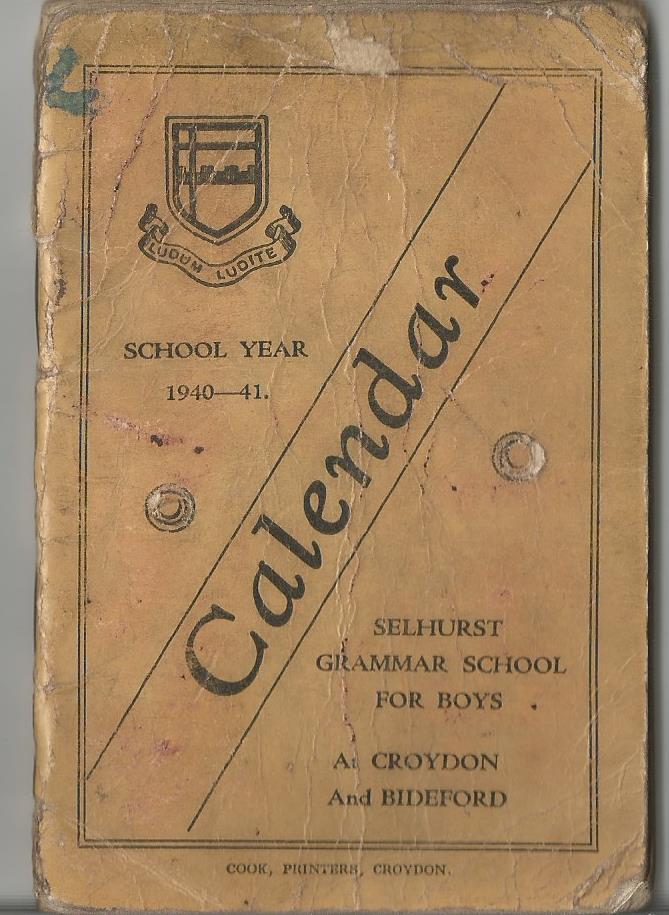

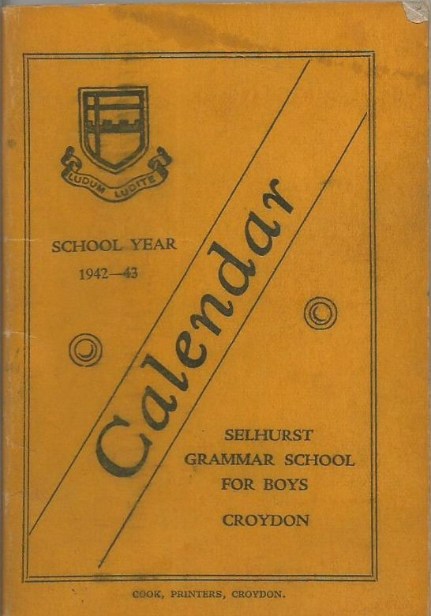

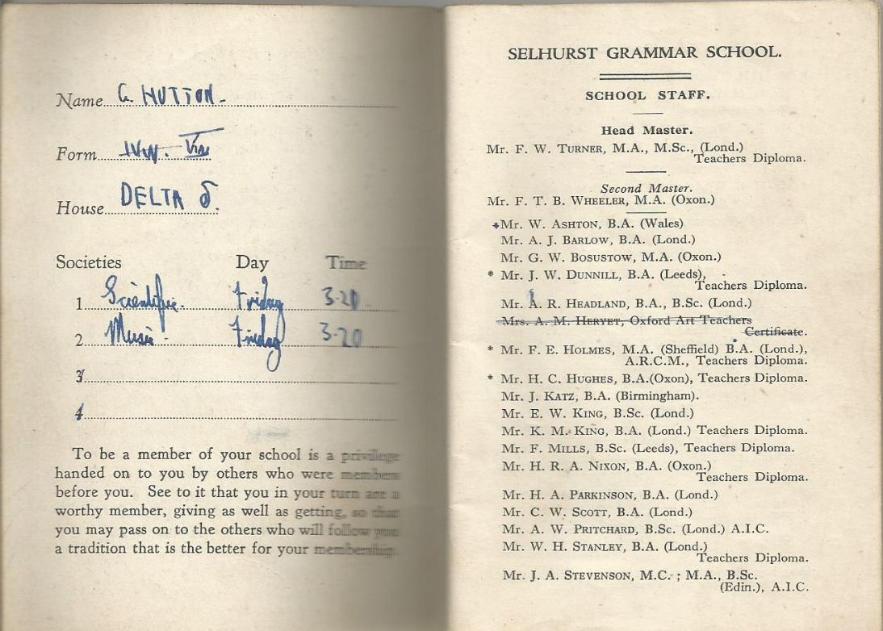

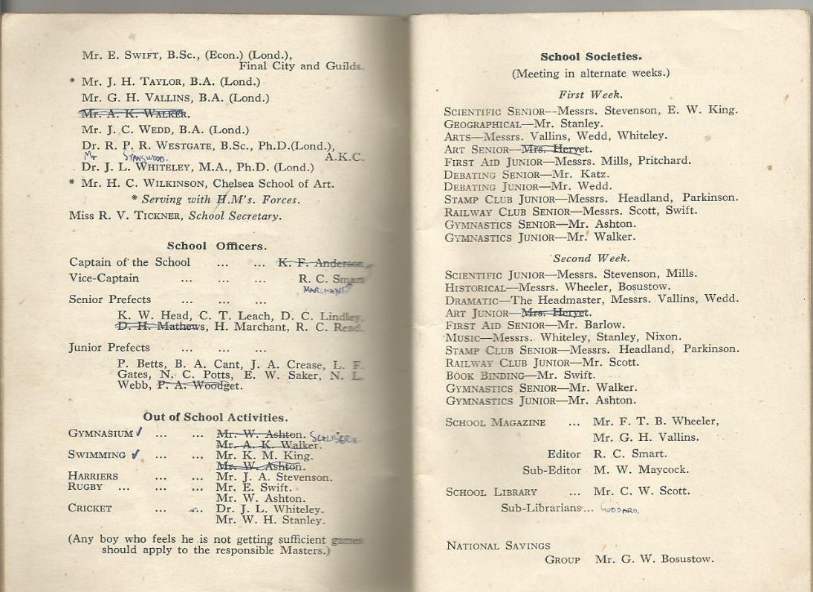

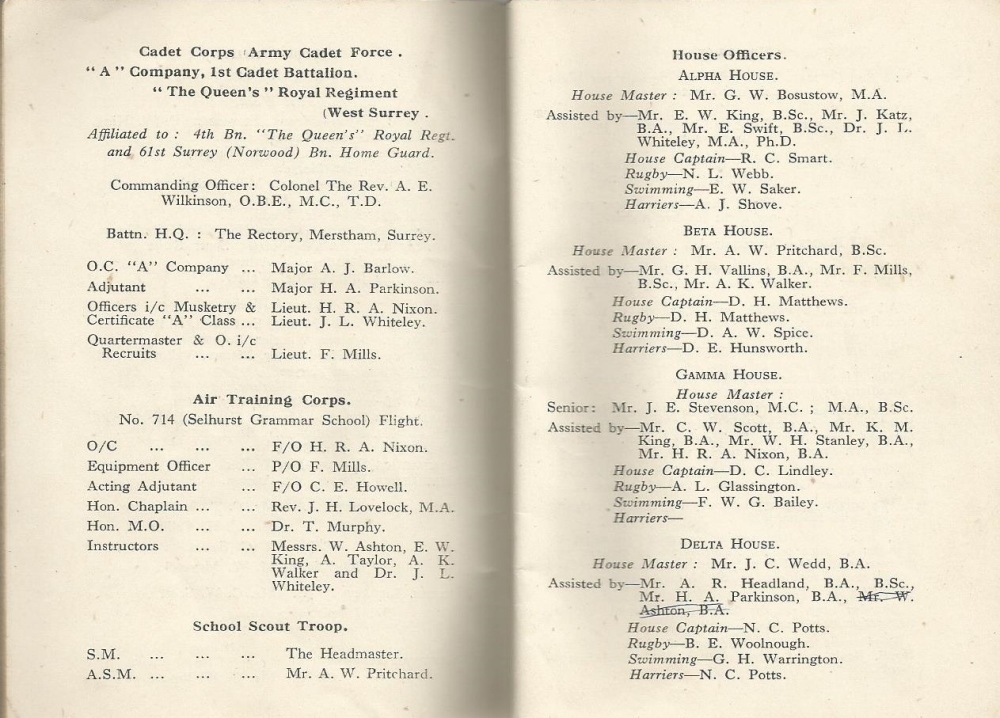

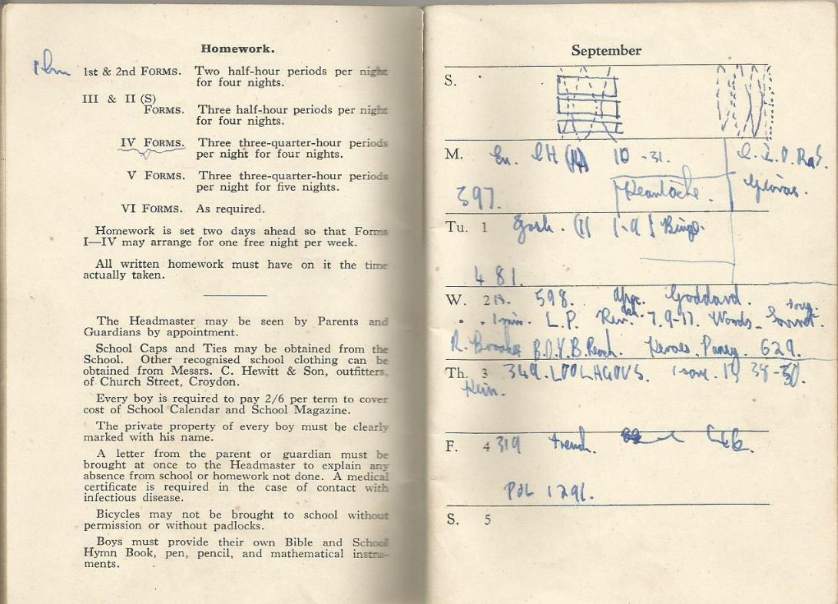

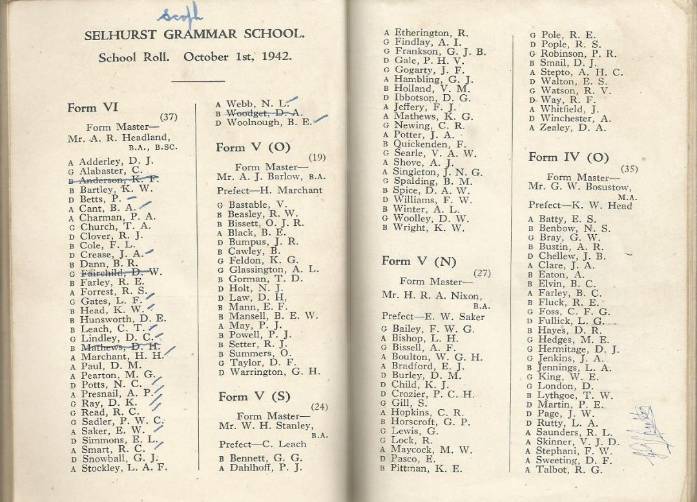

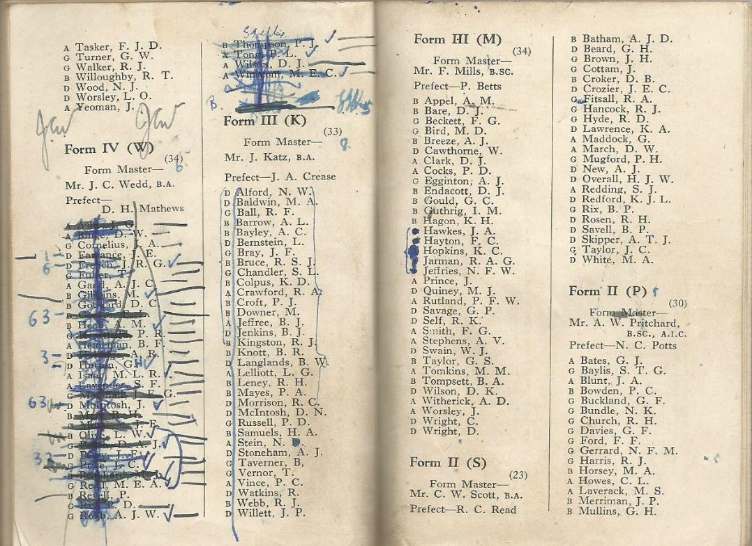

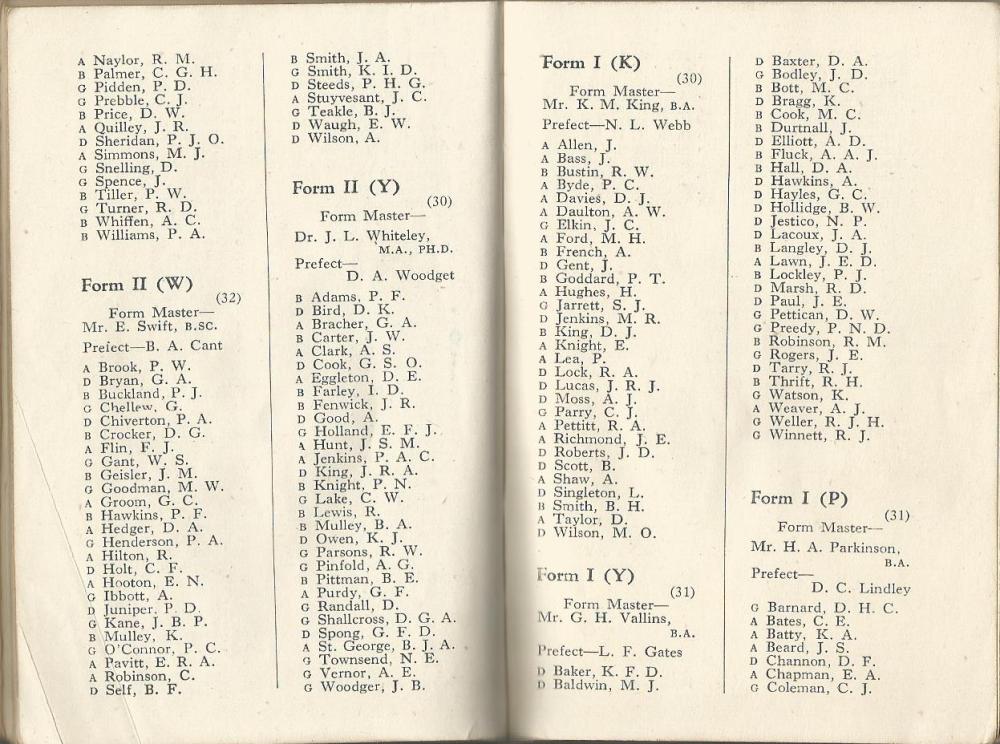

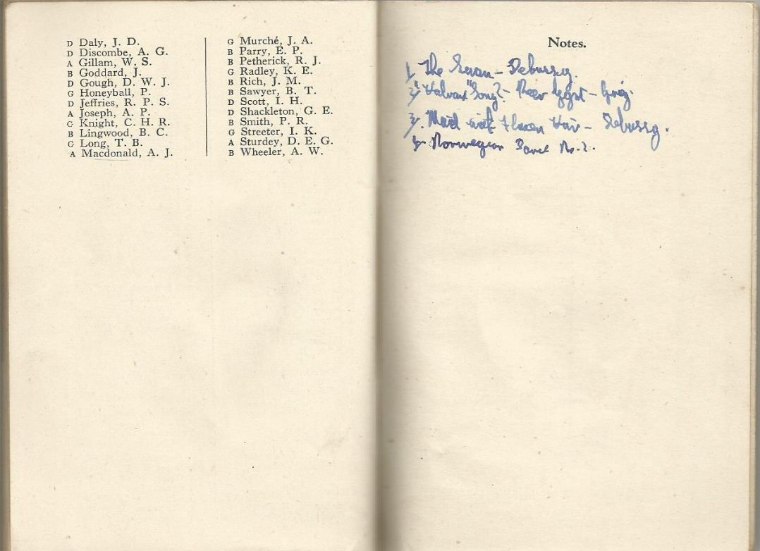

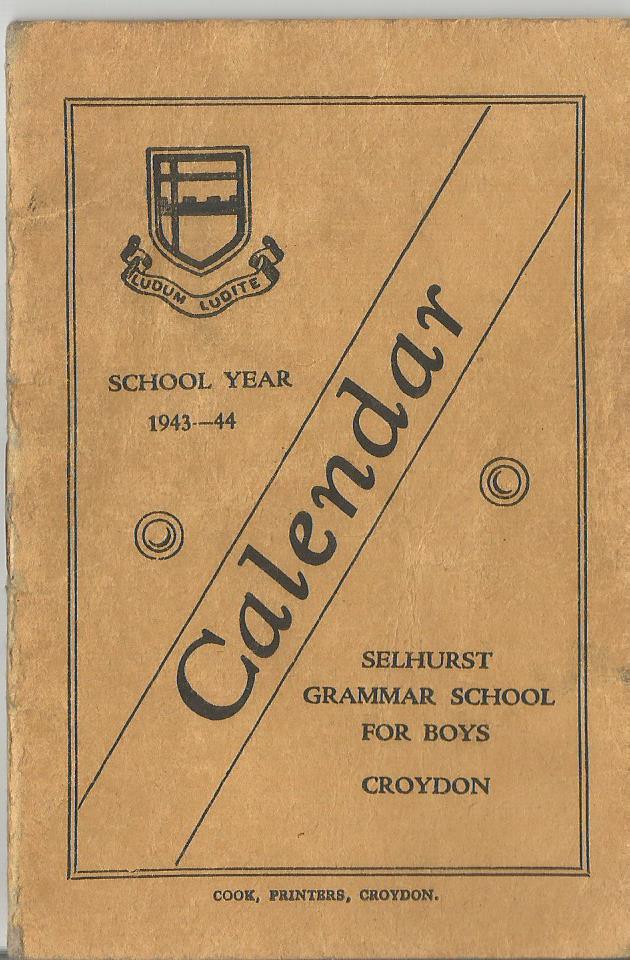

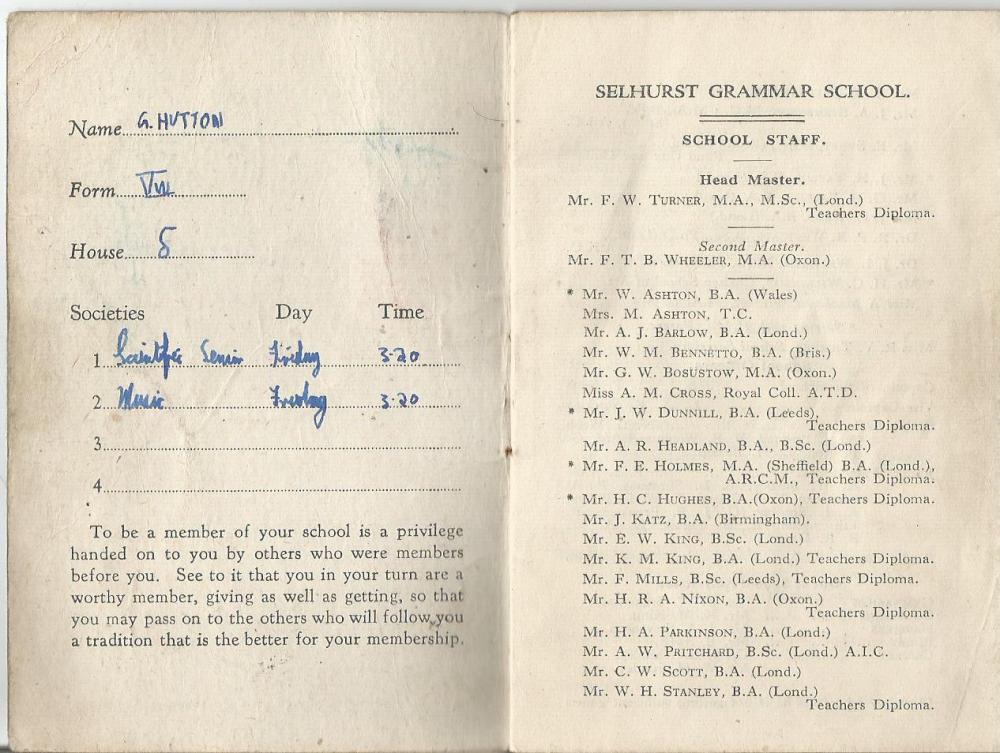

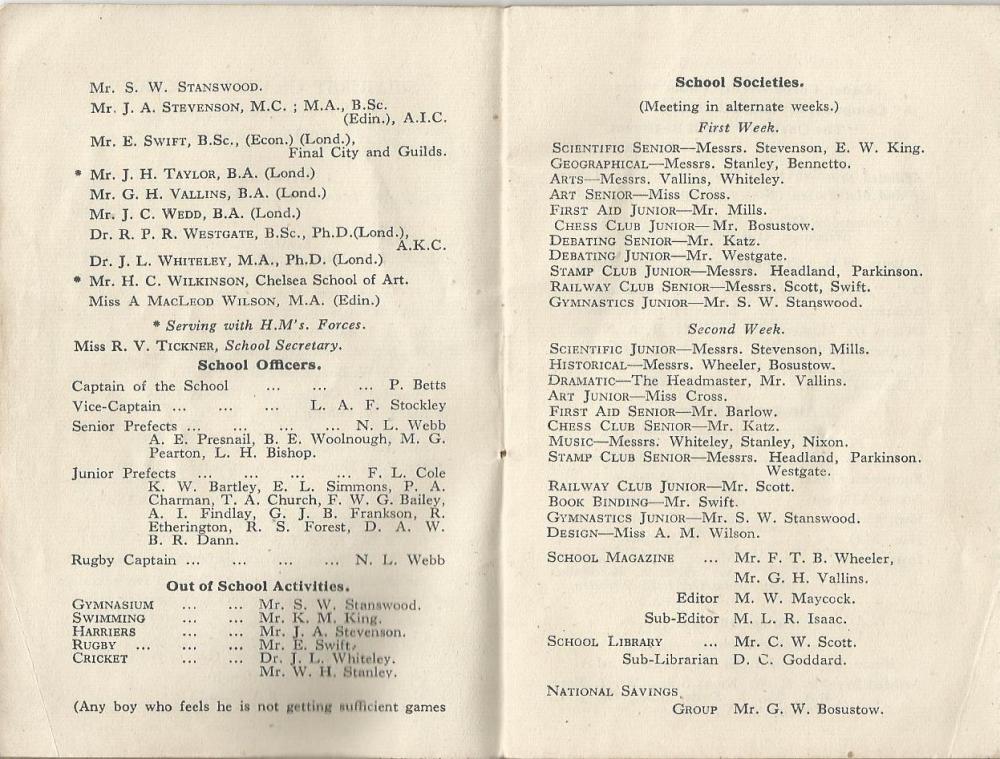

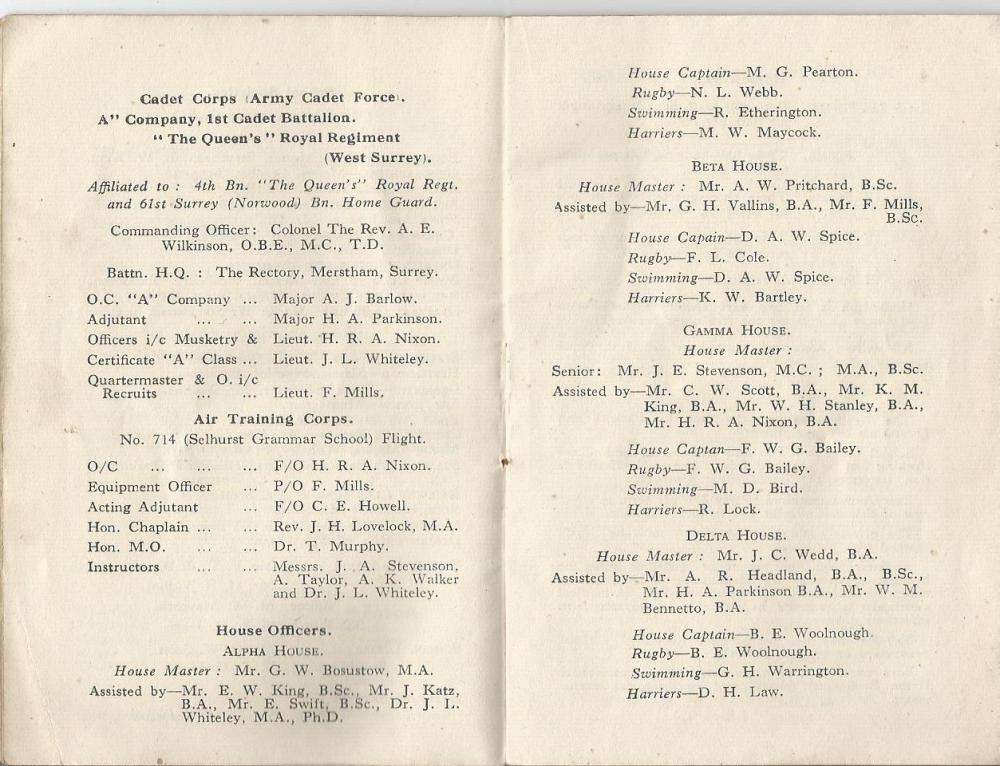

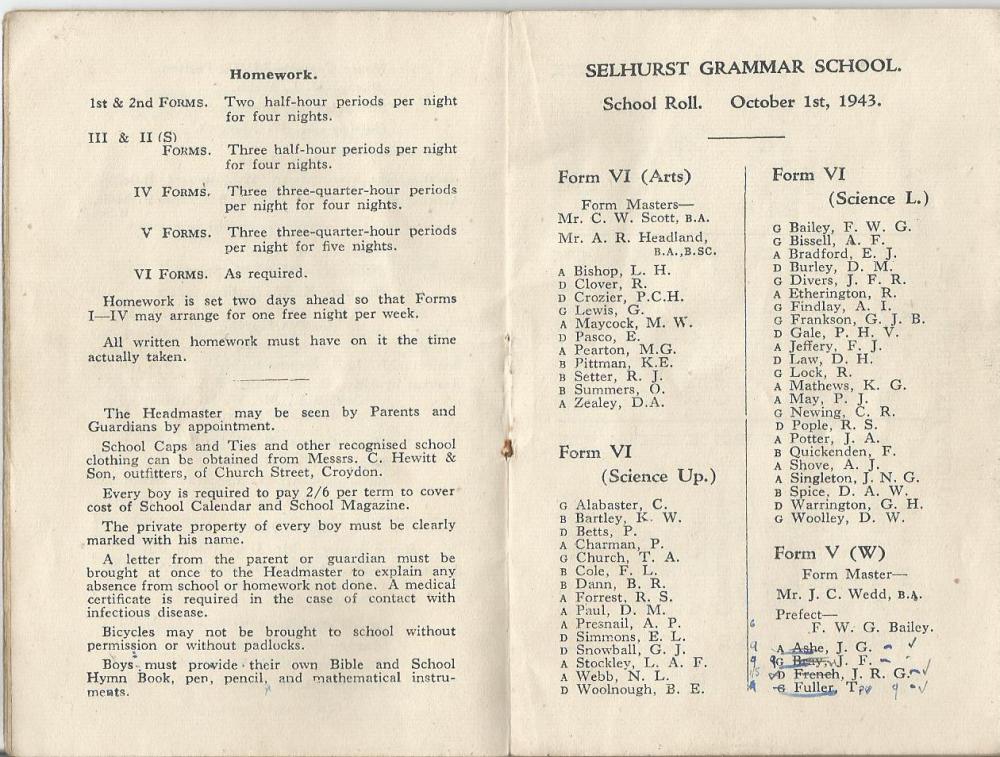

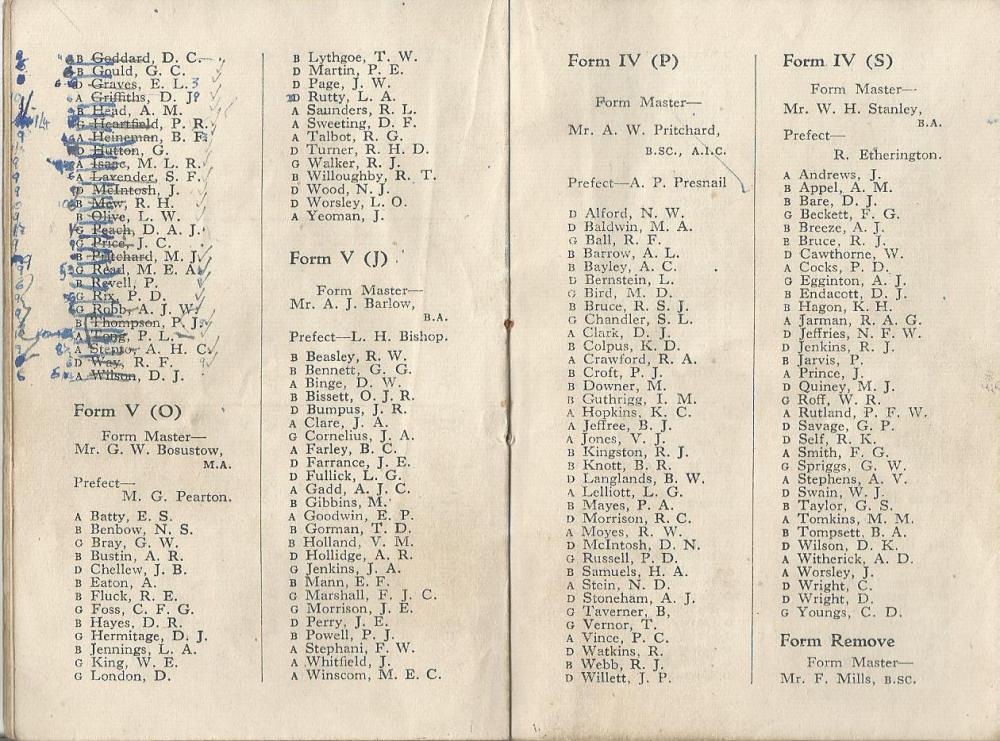

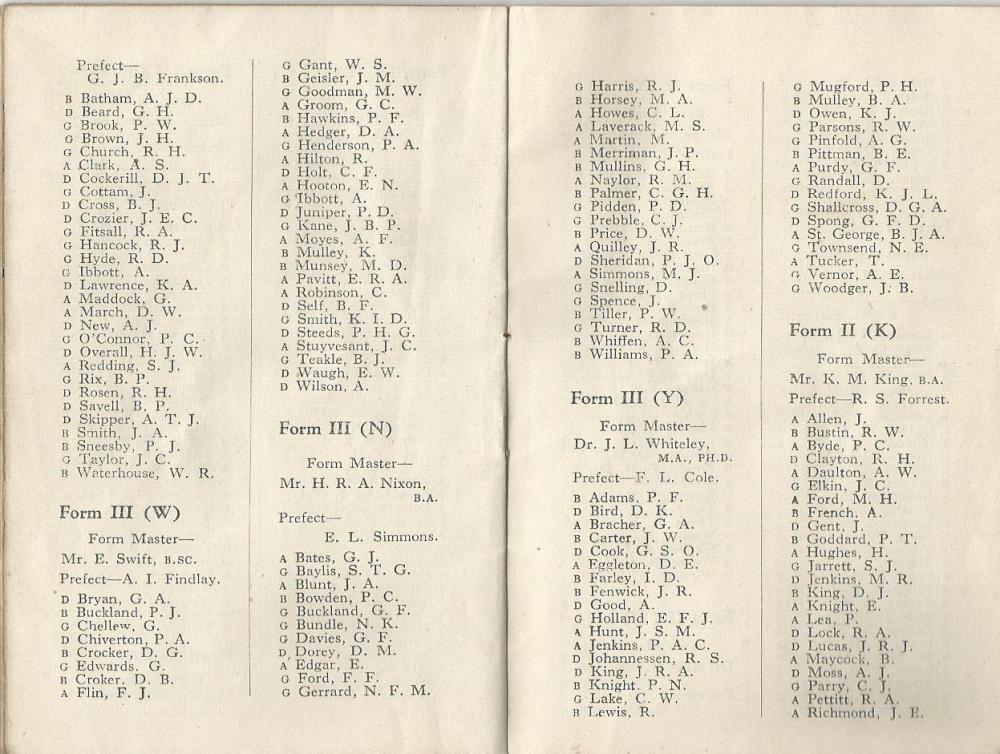

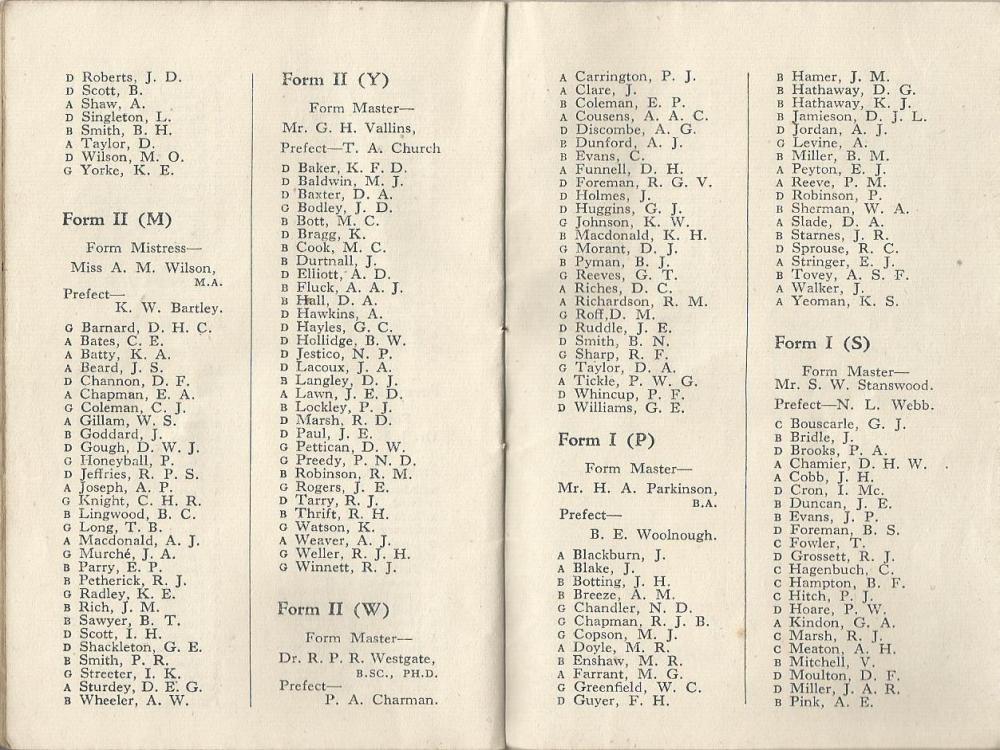

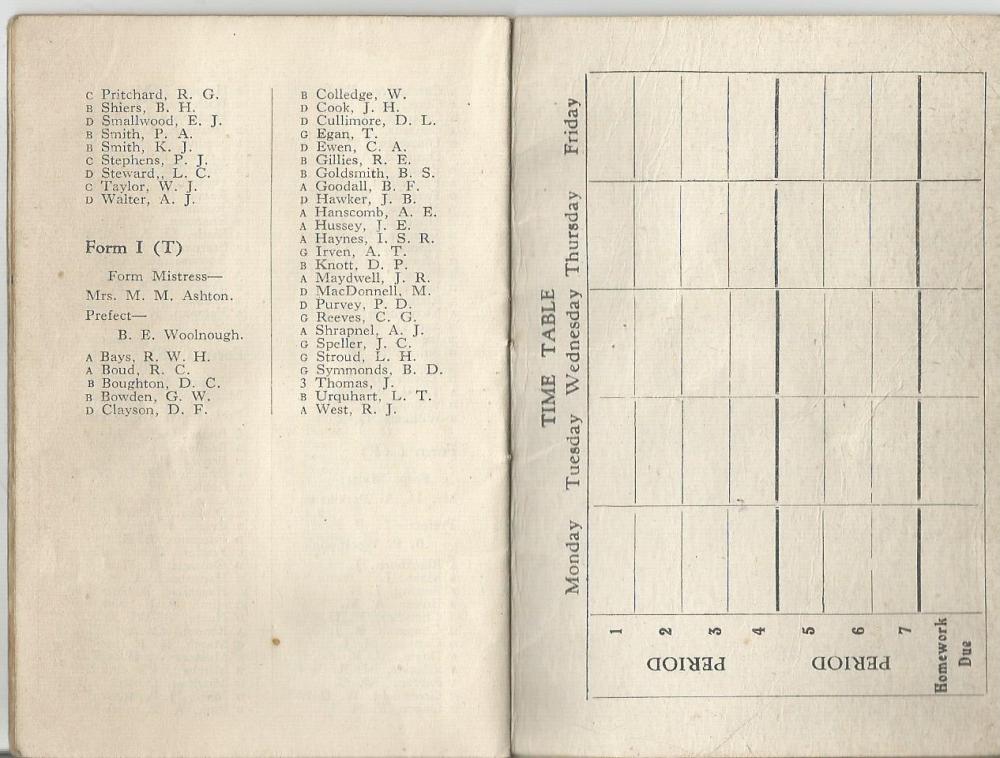

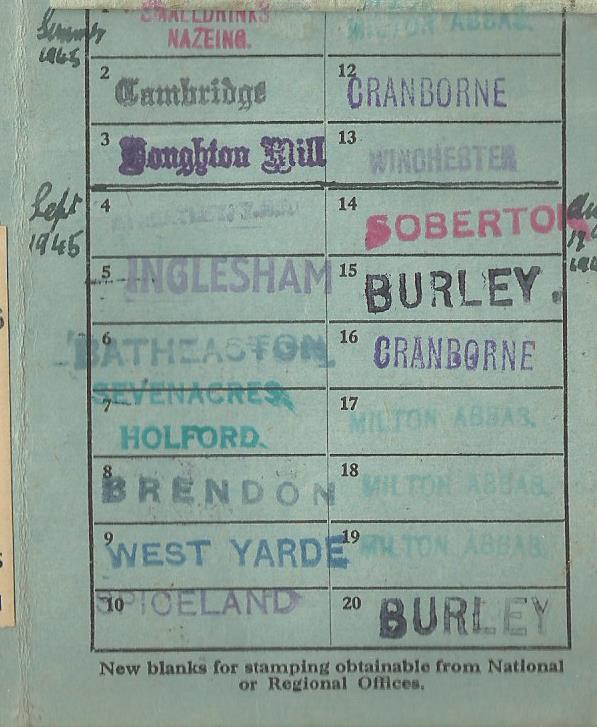

Geoffrey's school calendars

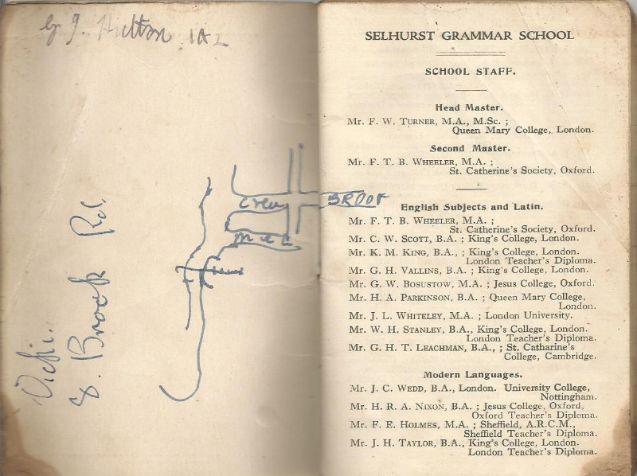

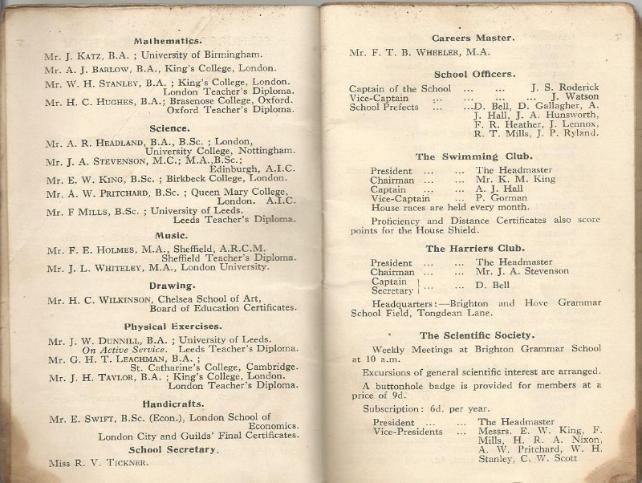

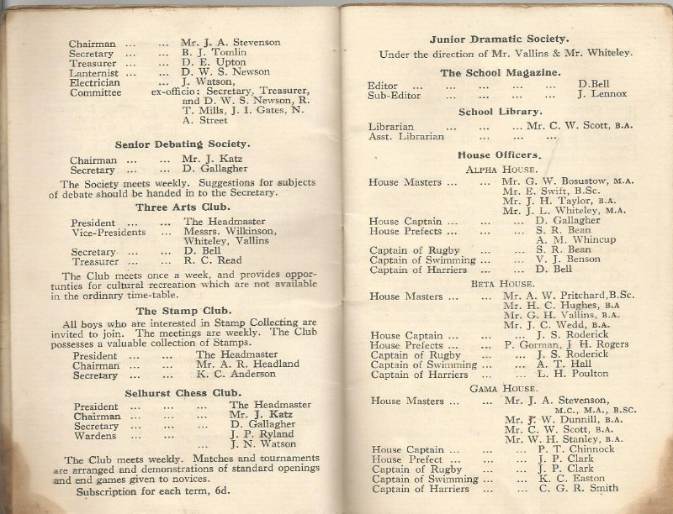

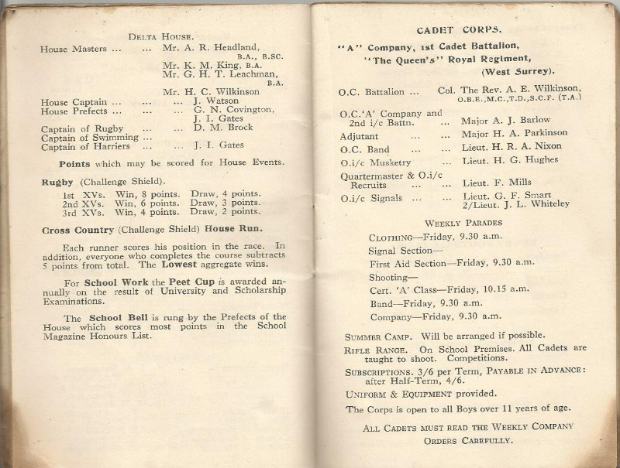

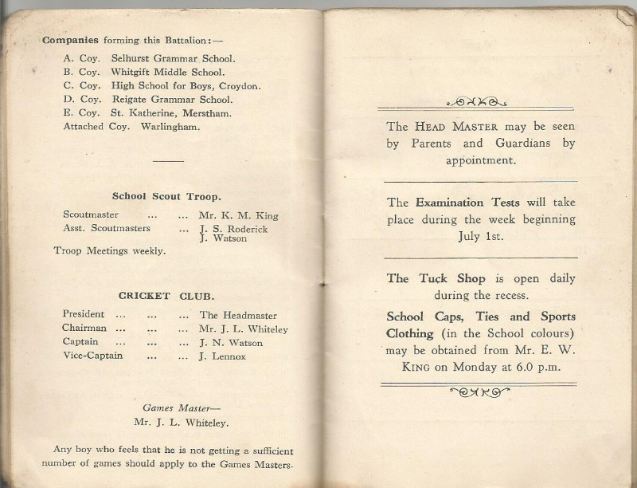

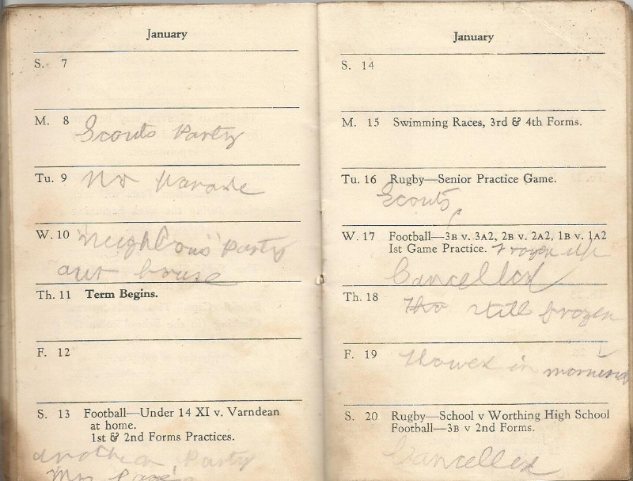

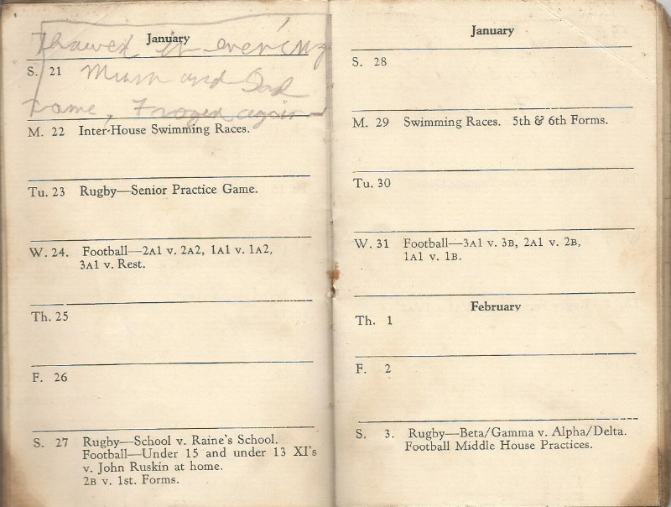

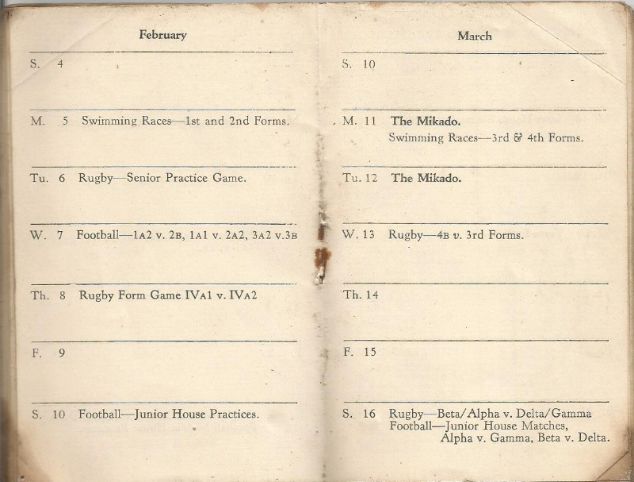

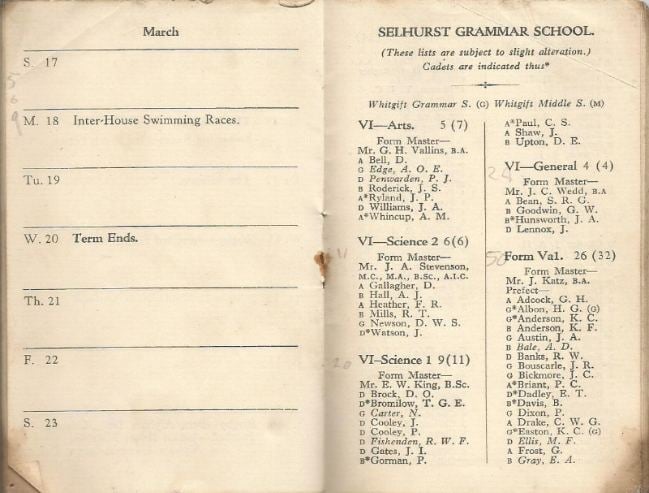

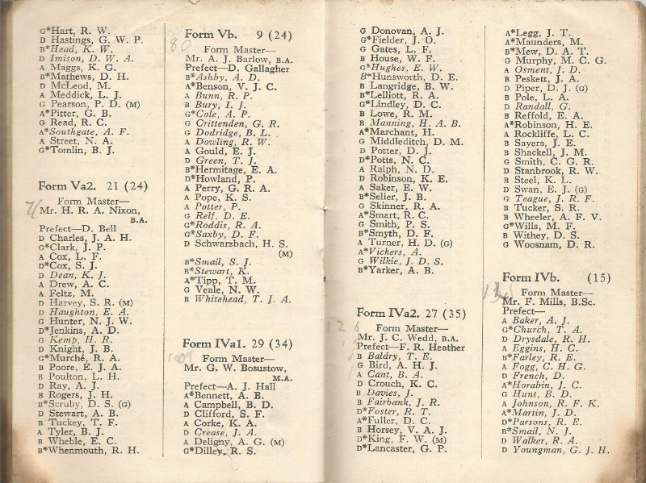

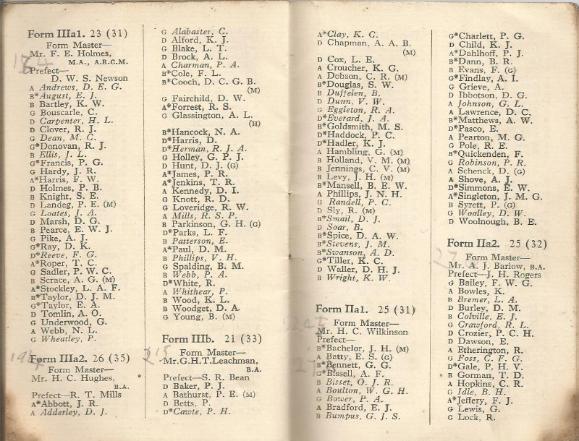

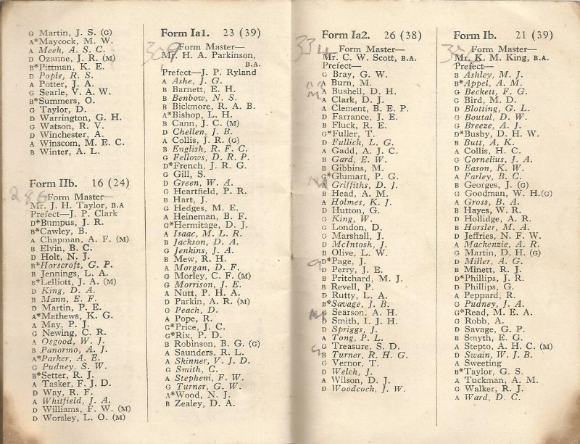

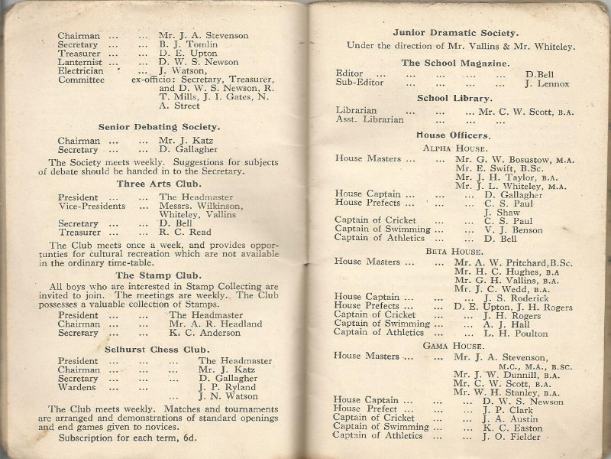

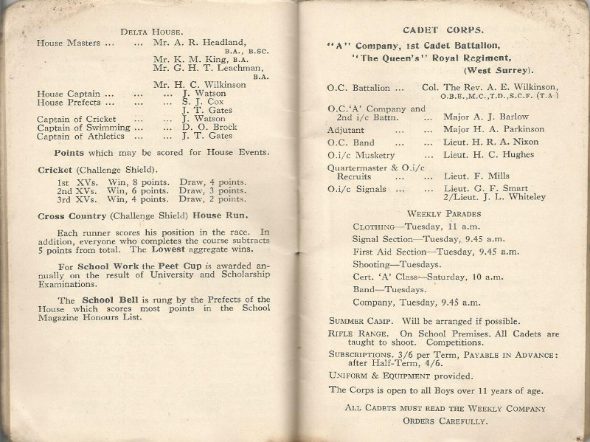

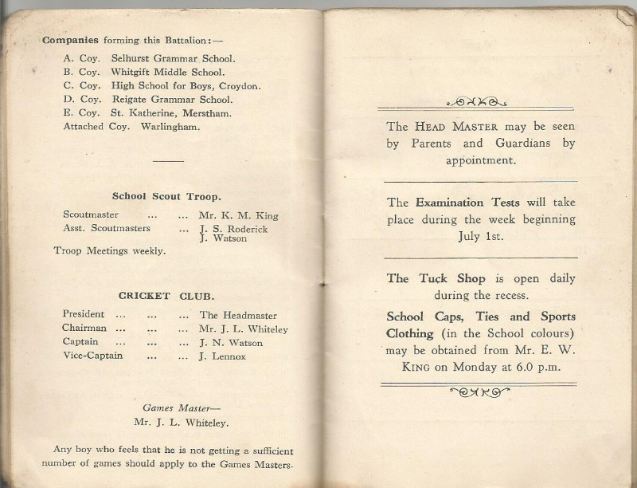

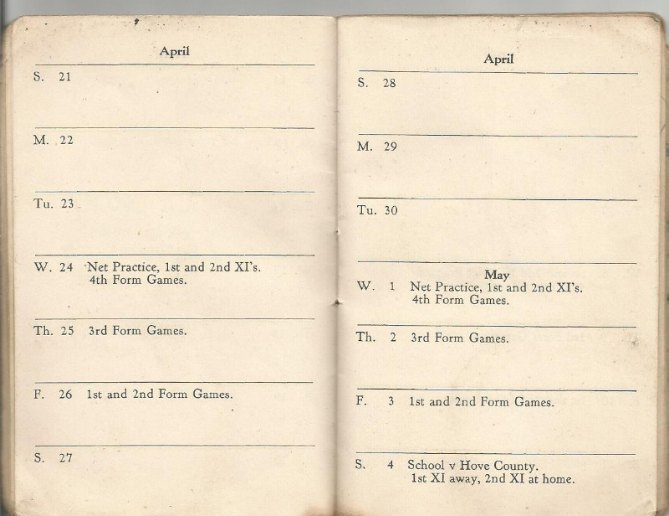

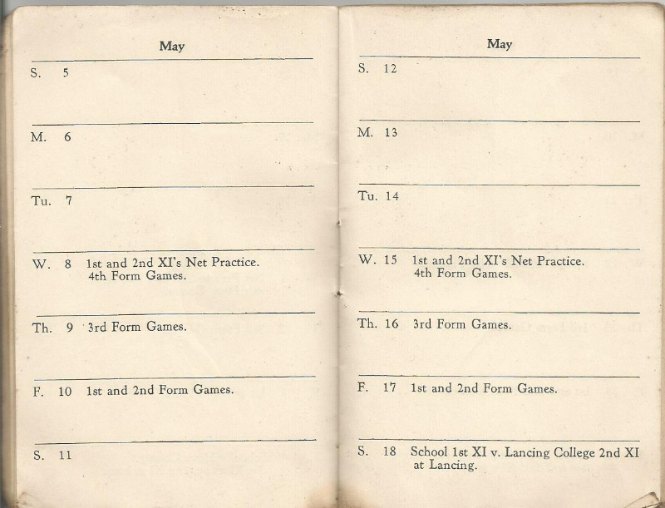

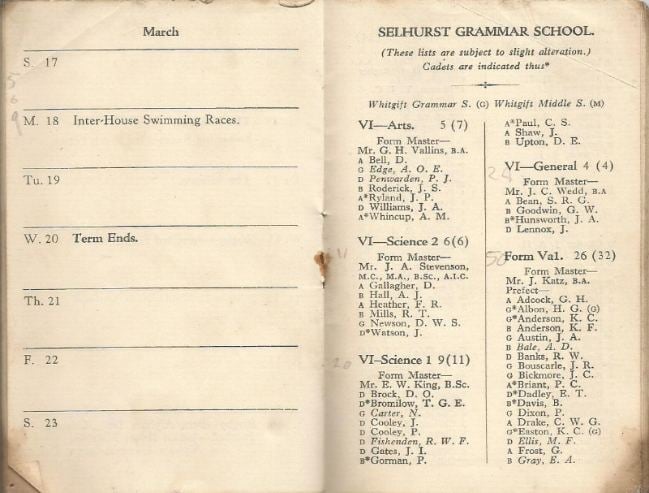

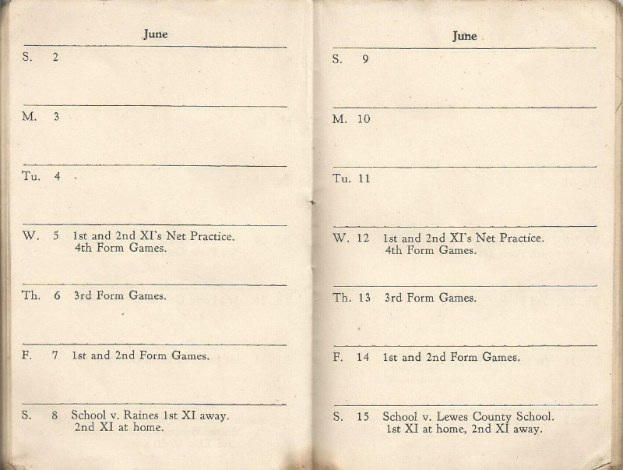

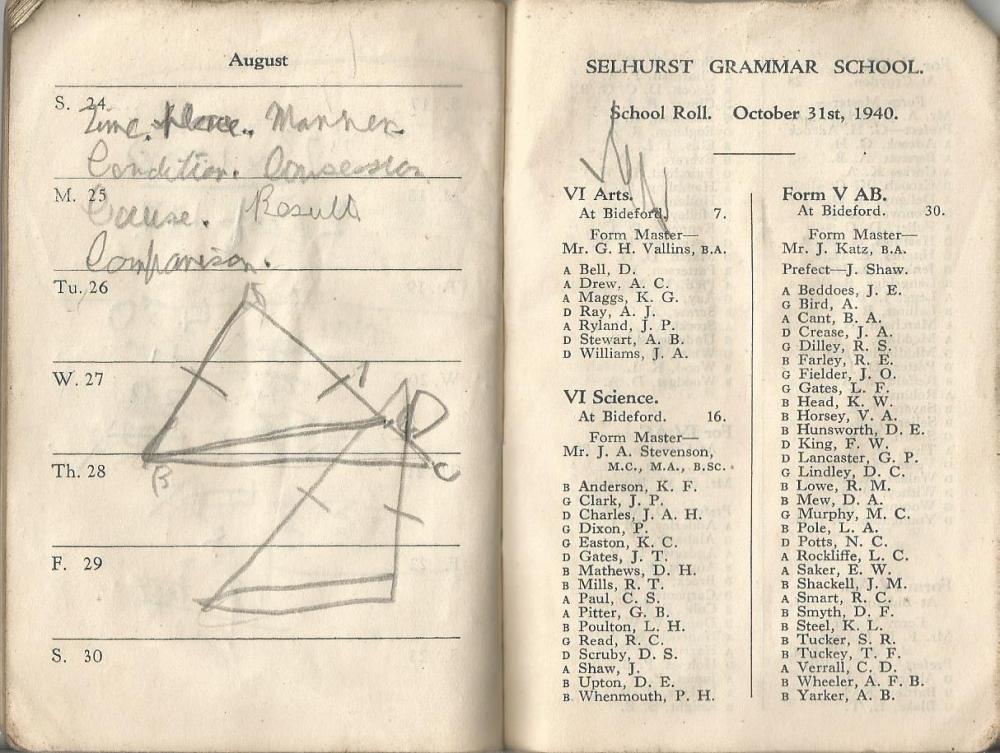

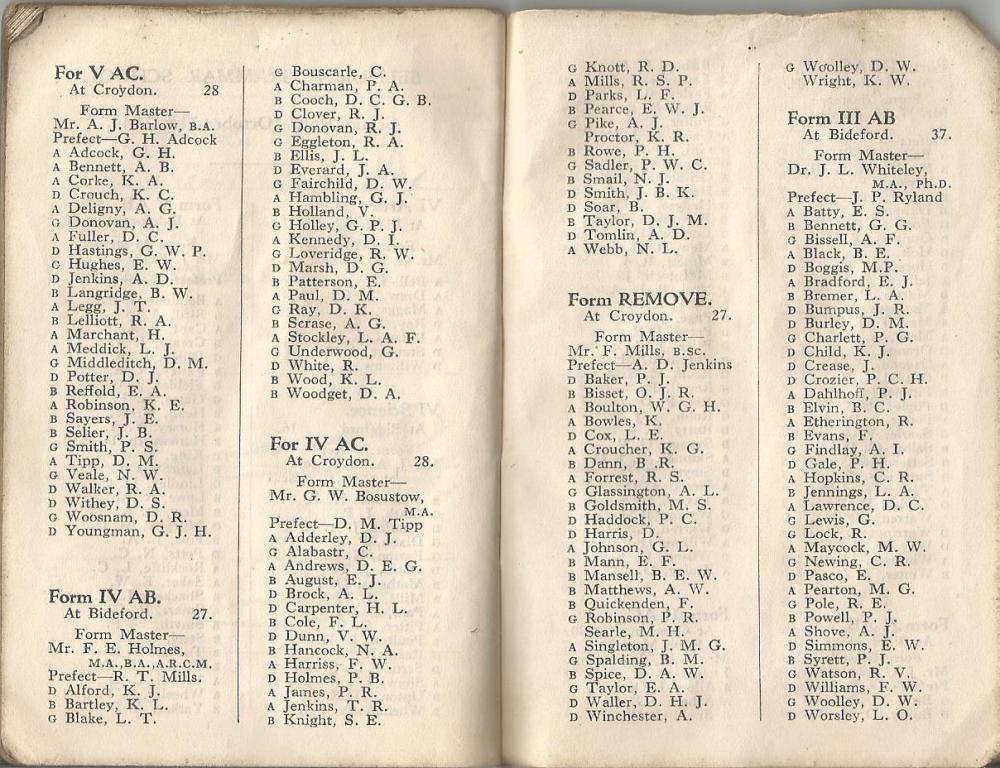

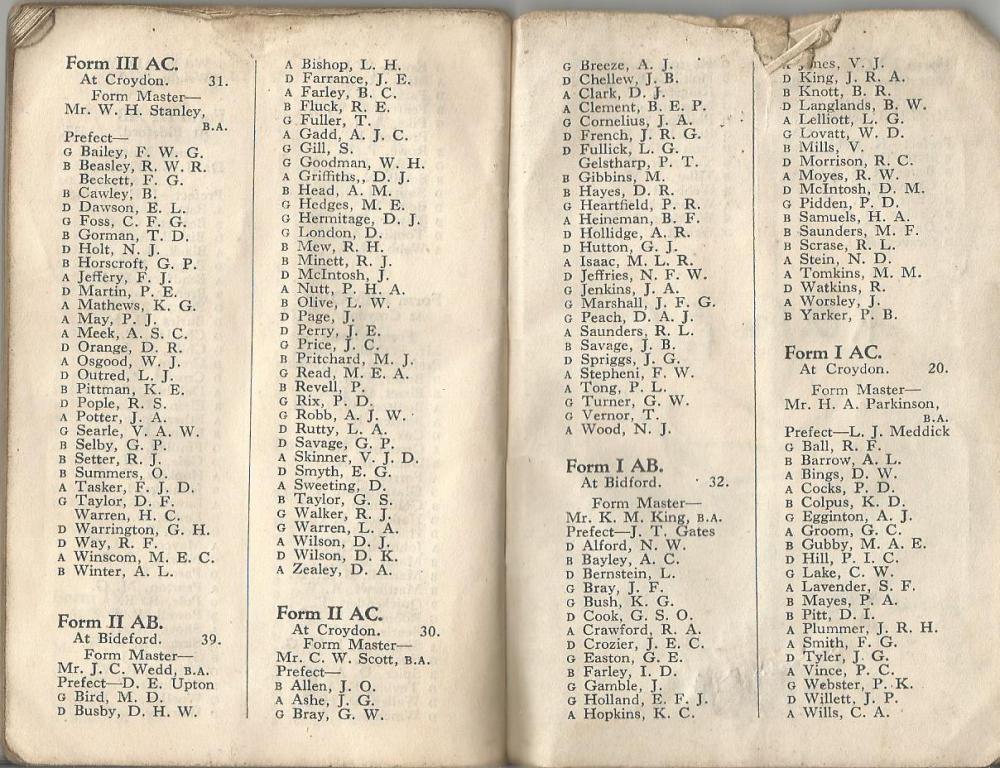

Selhurst gave each boy a little printed calendar. This was a list of staff, pupils, a diary with sports events and space for timetables, etc. I am showing here the complete calendar from his time evacuated at Brighton. I don't have 1939, but I do have from spring 1940 onward. Here are some, sprinkled throughout this page.

Selhurst Grammar School Calendar Spring 1940

The complete innards are reproduced here

I like the social aspect here. The family dad stayed with must have had a good social life and he was invited to the parties. 'Party at our house.' Nice.

The weather thawed. My grandparents went from Croydon to Brighton to see him on the Sunday in the motorbike and sidecar.

Each calendar lists all of the staff and pupils.

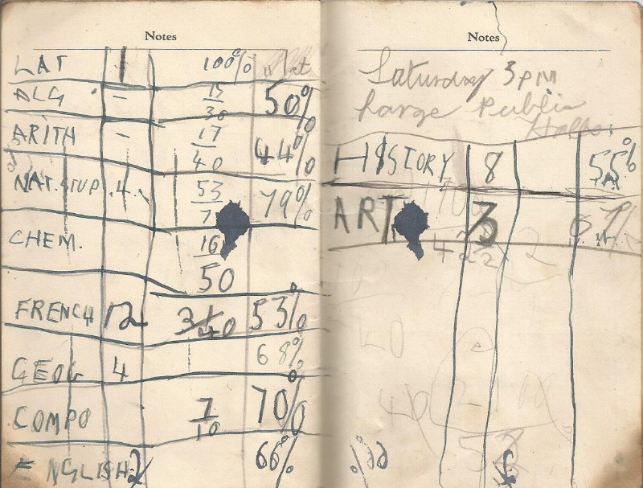

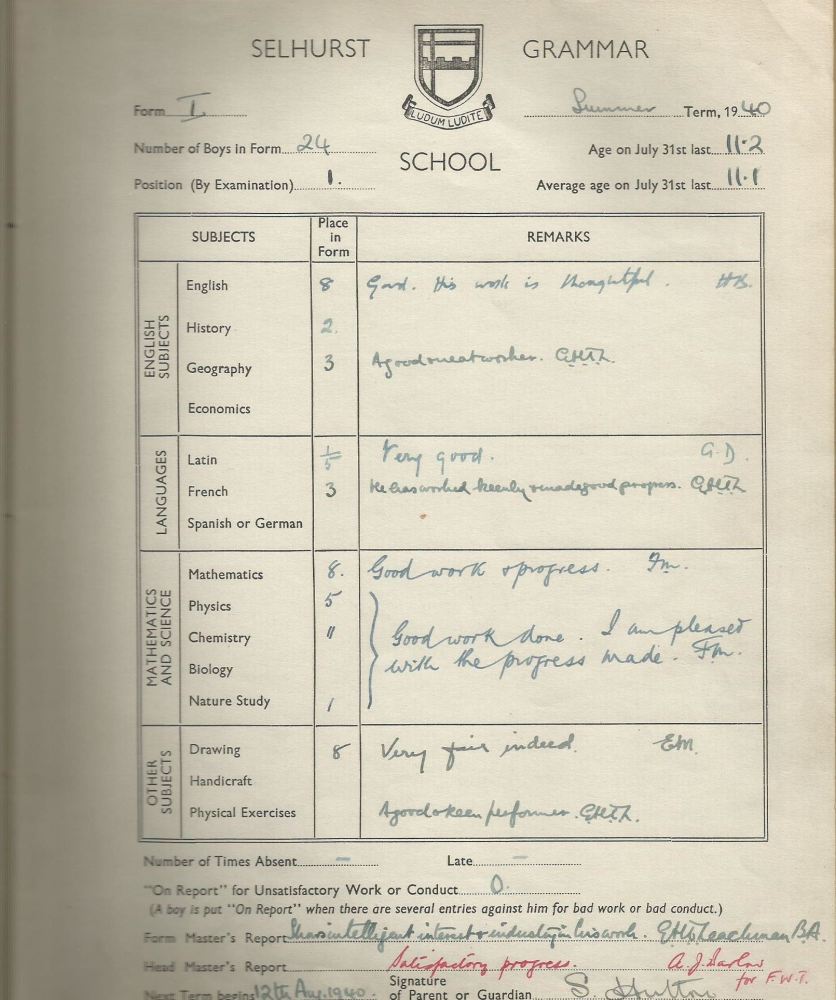

Lastly, here are his exam results. Yes he famously got 100% in Latin!

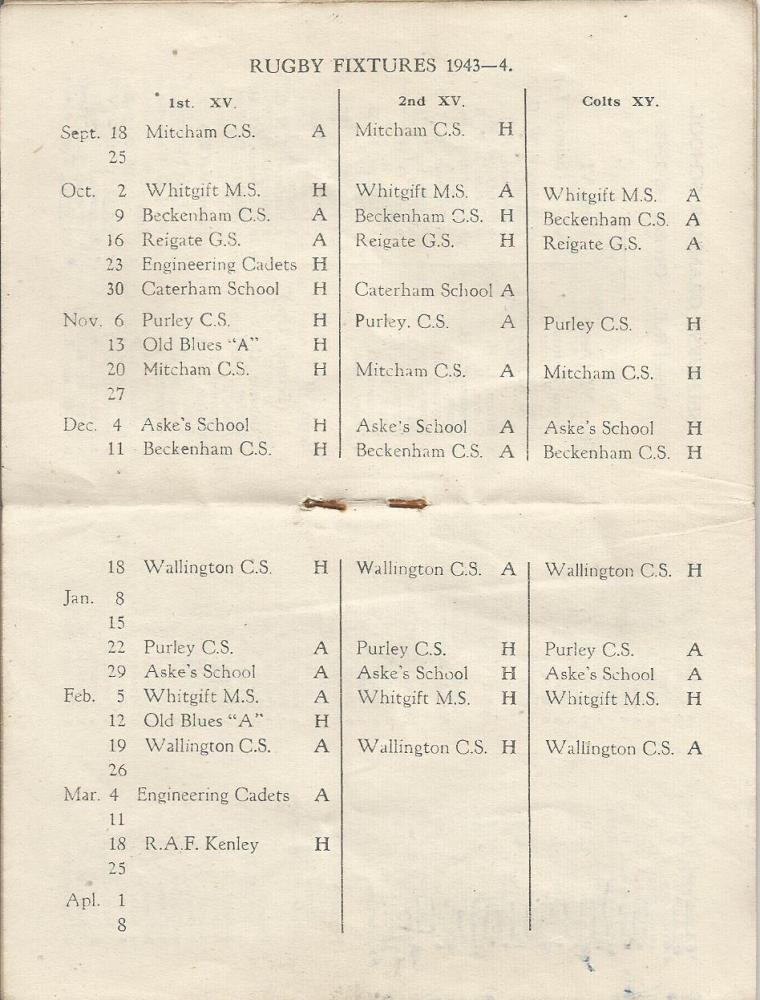

It is a testament to British organizational skills that the school could organize these sports fixtures with schools local to Brighton, and get this calendar printed at such short notice during a war as if nothing odd was going on.

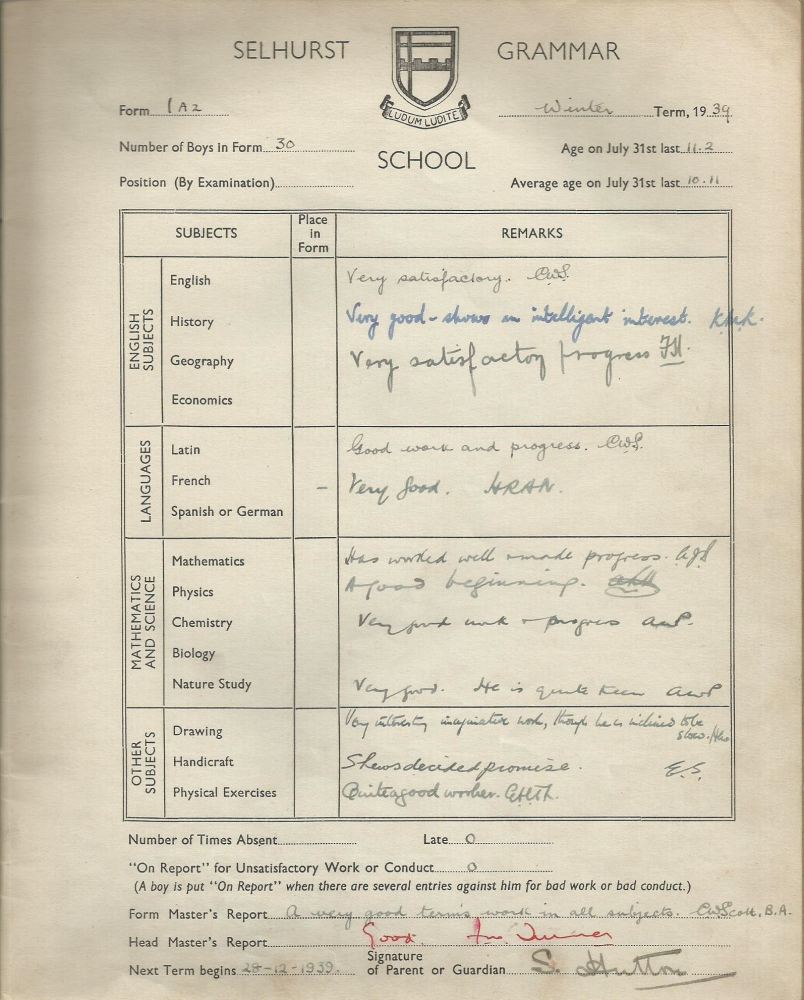

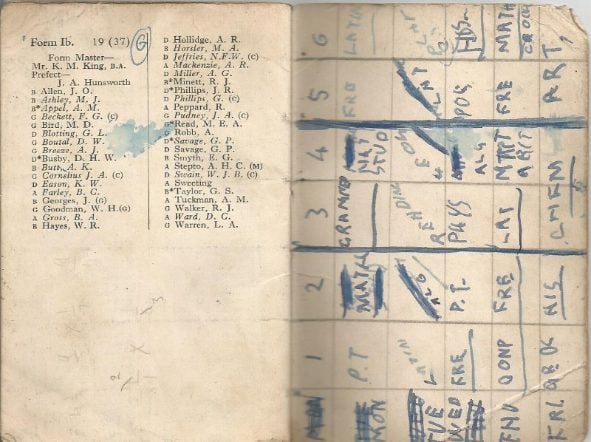

Selhurst Grammar School Report Books

Before I give the report for the term just shown above, here first is Geoff's school report for the 1939 winter term at Brighton, for which I don't have a calendar.

His good results, aged 11, away from home in wartime, are a testament to the family he stayed with (he was very lucky), to his own ability to adapt, and to the school.

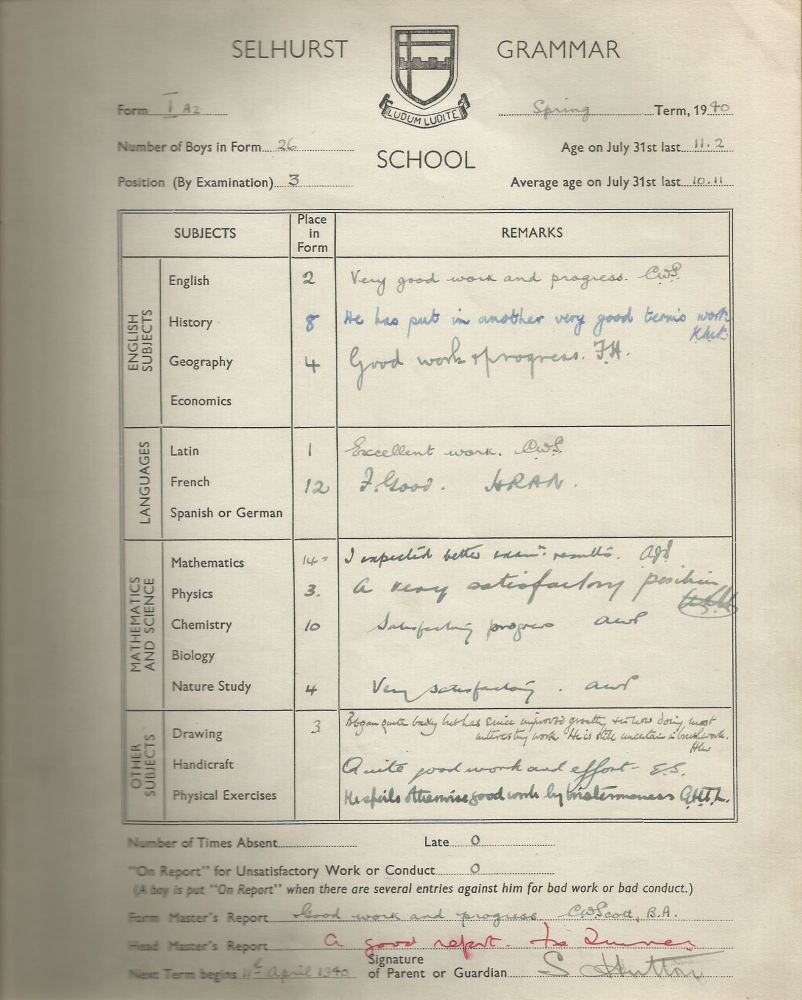

Here is the report for the spring 1940 term that we saw above.

Note the number of pupils in the class. It varies each term, presumably those children who were taken back home for one reason or another.

One day, about Easter time, Mr Brighton took me aside. He wondered if I had noticed Mrs Brighton. She was going to have a baby (well, now he came to mention it, I realised I had noticed). This was the notice to go. They couldn't keep me when it got nearer for the baby. I felt disappointment and something of betrayal and rejection, but I hope it was just the disappointment which showed. I suppose you could say they tried it out on me, and decided it was alright. When I left, I promised to come and see them again.

Mum came down, and we did look at another billet, where a friend from school was staying. He said it was fun there. It was a big terrace town house in Brighton, with a great kitchen in the basement. A lot of lino, and all very polished. Seemed very institutional and cold. I suppose I made enough fuss to be taken home.

It was a beautiful summer, the summer of 1940, with clear skies for weeks- it seemed like the whole summer. I was home from Brighton. Evacuees were drifting back. It was still the 'phoney war', with no action in France. Arthur was there. "We're going to hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line, if the Siegfried Line's still there". I must have heard that at a pantomime in Brighton, as well as on the wireless.

The school opened a little rump unit in Croydon. It met in the adjacent girls'school, and was a combined operation. For just one term, we had co-education. I liked that, and would have been happy to stay with it. As soon as the Germans attacked through the Low Countries, Brighton rapidly became not a very sensible place to which to evacuate children for safety. The school split, half coming back to Croydon, and half going down to Bideford. That was the end of the co-eduational interlude, as we moved back into the boys school. The building, although a twin to the girls' had seemed more severe in character on the odd occasion on which we had looked in - darker wood and panels of gilt names.

Some seven or eight years later, when I was in the army, I went back to Brighton on one leave, to look up the Brightons. There were different people in the house, and they gave me the Brightons' new address. It was a terrace house nearer the centre of Hove, but there was no-one in. I wondered what happened, as it seemed to be a coming down in the world. Had there been some sort of misfortune to them or to the business - there wasn't a lot of sweet making during the war. Had Mr Brighton gone into the army? I left a note, but I never heard.

Croydon

At home it was a bit chaotic. Mum and Dad were doing their bit. There were lodgers in the house, or rather billetees. We had soldiers billetted. They were occupying the spare bedroom, and the front room. Sometimes there were more than that, and it seemed that we had sleeping bags and camp beds everywhere you turned. I think it was only about seven we were putting up. They were in transit for Europe mostly, and many were not real soldiers, although in uniform. They were NAAFI managers, Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes, which were a sort of club, where refreshments and entertainment were provided, as I learned myself later.

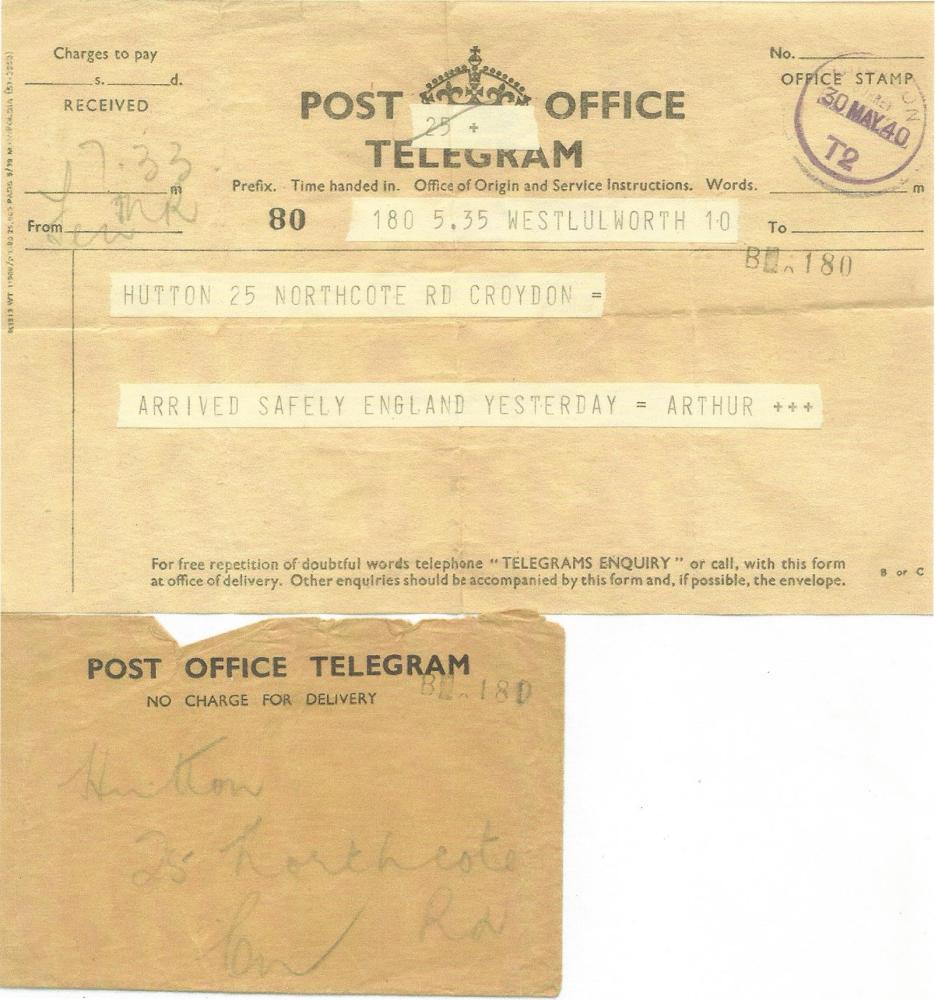

It was one particularly packed night in June, when we all had a sort of party. News was bad. The Germans had invaded France and were advancing fast. The British Expeditionary Force, in which my brother was a dispatch rider, was being pulled out through Dunkirk. We hadn't any news of him. Anyway there was a phone call from the operator asking if we would accept a transfer charge call from a Mr Hutton at Dover. Dad, or Mum, I've forgotten, said no, we didn't know a Mr Hutton at Dover. It was Arthur, returned from Dunkirk. His telegram came later.

The telegram was sent from West Lulworth, so he either landed at Lulworth then went to Dover, or the other way around.

Arthur came home a few days later and what a reception. Arthur and a couple of mates had picked up an abandoned lorry and made their way independently across France to Dunkirk. There, because of he lorry, they were directed almost immediately to a transport, and so didn't have to wait on the beaches. They were hungry on the journey, and have told us how they had gone into an empty farmhouse looking for food, and all they found were the remains of a meal, with some cold boiled potatoes far from fresh. They ate them. So imagine the relief of getting home, though with not a penny, hence the attempt to transfer the charge. Mum tried to excuse us by saying "Why ever didn't he say Arthur?" Not that there was anywhere for him to sleep. I can remember sleeping on the floor of the living room, with Arthur's .32 revolver under my pillow.

Amid all of this, school life continued, as normal as possible.

Selhurst Grammar School Calendar Summer 1940

Here is the report for that term...

It is nice for me that my grandfather has signed the reports. His signatures are the only example of his handwriting that I have. The reason that my grandfather was at home during the war is that he was in his 50's! He was an Air Raid Warden and in the Home Guard.

Dad had joined the Civil Defence at the beginning of the war, and was an Air Raid Warden. He didn't get involved much in air raids, because after Dunkirk, the Local Defence Volunteers were formed. Dad went round the first day and signed on. He had been rejected for military service in the first world war on medical grounds. (Flat feet we presume). Now, he was sort of in the army. That is, he had an arm-band saying LDV. Later on it changed into the Home Guard and they got army uniforms and guns. I fetched a gun from round the depot corner for Dad. It was an American rifle of odd bore, with odd rear sights, a round ring. Anyway, I felt very important carrying it through the street.

Croydon Home Guard. Geoff's father is third from left, middle row.

A tin Air Raid Warden sign was put in their front window to show where he lived. Geoffrey kept it in his study after his mother died in 1974 and we still have it.

He said that during the war his father had seven men working for him in his building firm (there was a lot of bomb damage to be cleared and shored up, etc.) They called my grandad 'Guvnor'.

The summer remained fine, right through to the ensuing Battle of Britain. That was a daylight affair, with the skies laced with vapour trails from dogfights. The sound was muted and distant but quite clear. Pop, pop, pop, pop. Great bangs from the ack-ack. Still called ack-ack, from the First War pneumonics for A.A, anti-aircraft. We got used, later, to talking of 'flak'. Fliegerabwehrkanonen. The anti-aircraft guns and balloons were sited in open spaces around the town, where we used to go sometimes, before and after. Sometimes the bangs were nearer, and I wonder if the guns were moved about a bit, temporarily.

Bombings

The night raids had a pattern. The sirens late in the evening, little activity for most of the time, then sounds of distant guns, and the aircraft engines. You could tell the difference between Heinkels and Junkers. There was an engine noise quite deep, with a pulse to it- that was the Junkers. The Heinkel was more regular. They were often passing over on the way to London, or coming back, but we had some bombs. Bombs didn't so much whine or whistle coming down as make a splitting noise. They sometimes sounded so near that I was sure this one would get us. I was scared, but reprimanded Mum for exclaiming. Then there would be a lull, with perhaps a repeat.

In the mornings, the near-sounding bombs proved to be some distance away, though known buildings were gradually replaced with bomb sites, at first broken heaps, neatened up later with emergency water tanks on some. The streets would be scattered with shell splinters which we called shrapnel, though that was properly the name for splinter-producing shells from the last war. There was sometimes glass or chimney pots, so apart from any proper rescue or clearance activities of bombed premises, there was a bit of sweeping and tidying to do. It wasn't until the flying bomb raids, by which time we all thought air raids were over, that the immediate neighbourhood was hit and the daily scene changed sharply and suddenly. Although we children collected splinters and cannon shells avidly at first, it must soon have palled. Funny that of all the bits I have kept as souvenirs, I didn't keep any for long and haven't any now.

You would hear where the bombs had landed, from people in the street, or I suppose from school too. The local paper would list the casualties and damage. Unexploded bombs or land mines were news, too. They were marked, and defused or exploded. So there was sometimes a bang when there wasn't a raid.

See base of page for more on the air raids.

The Wall Map

It was on the wall of the living room, just inside the hall door. It may have been published by the Daily Express, which was the paper we had. It covered Europe and the Mediterranean. There were also provided little flags which could be cut out, wrapped around a pin and stuck in. For several years I plotted the progress of the various armies, from the invasion of Russia onwards. It's a very good way of learning where Mersa Matru and the Dnieper were.

As the war flowed back and forth, the map got a bit pierced. The effect was apparent along the North African coast, as the Eighth Army went backwards and forewards about three times. In Russia and the Ukraine, the war went mostly one way and back, but there were smaller advances and retreats so that some bits of the map were mostly holes, as was Stalingrad. Advances in North Africa were so fast in comparison, and the excitement mounted as the final advance went further and further, especially since Arthur was in it. The map served for the advance up Italy, the Second Front after D-Day and the meeting of the Red Army and the Americans in the middle of Germany.

D-Day was so exciting. It had been expected and discussed for so long. We knew the Russians kept asking for it, and that preparations were going on. But the announcement that "early this morning the Allied troops landed on the coast of France" still makes me want to cry.

We weren't supposed to know about preparations, and indeed we didn't know much. Except that one couldn't travel into the Restricted Area on the East Coast. That included Canterbury and Blean, where my sister-in-law Joyce's family were. I used to visit during holidays. Mr West, who was a commercial traveller for a stained glass company, used to get me in. He would meet me outside, and we would get off the train together and march past the armed guards, he showing his pass and saying "he's with me".

Joyce and my brother Arthur met on the telephone, when she was a telephone operator in Canterbury, and Arthur was using the phone from his unit.(Arthur and Geoff's mother was also a telephonist before her marraige). They got married in Blean in 1941 and we all went down. Later I went to visit in the summer several times. The house was just outside Blean, on the road to Whitstable. It was brick and square and sat well back on its own piece of land. Mr West was a formal sort of chap, usually to be seen in his business suit with waistcoat and gold watch chain. Almost pompous, but he taught me a lot, and gave me things, including the guitar. Mrs West was short, round and I don't think got on very well with him.

Joyce's sister Joan was another matter. She became the main reason for going, and we had quite a thing. She was about two years older than I was, and I'm not sure why she bothered. Anyway for a couple of years or so we wrote regularly, and made much of our time together, especially walking home late at night from Canterbury up St Thomas's Hill. It was only snogging, but had I been a bit further on, things might well have been different. That affair dropped away by the time I was sixteen or so, and she had joined the Wrens. I was getting a bit more interested in local prospects.

Joan never married and lived at the family house all of her life. I stayed once as a child in the 1970's. The bedrooms were decorated with beautiful wallpaper, unchanged since their childhoods. Blue with gold stars. I'd never seen anything like it. (When I got married, I did our bedroom in a similar paper). There was stained glass in many of the little windows. Of ships and things. Joan was a lecturer at the University, in Canterbury. She bred tiny dogs. It was one of the most memorable holidays of my life. I had no idea until I found this story today and typed it in here that she and Dad were involved in their teens!

The Blitz

Later in the year, the air raids changed to night-time, and went on through 1941 and later. We slept in the Anderson shelter dug out inside the shed. This had a concrete floor, and electric light, with bunks on either side. We didn't use it for the whole of the bombing, because I can remember getting up from bed when there was a raid. I reckon we went back to sleeping in the house. There was a while when at least Mum and I went to the Anderson shelter in the garden of a neighbour- the Arnolds. I think it may have been, during the flying bomb raids of 1944. I suppose we must have demolished our shelter by then. It was odd, getting ready for bed, and then going for a walk round the back pathway to next door but three.

F.W. Turner

He was the headmaster who joined when I did, and left a little before I did. In the early years, Turner was a remote figure. It was only during the first six months that we were in the same place, in Brighton. Until the school recombined, he was at Bideford, and the only visibility was that he signed some termly reports. After we were all back at Croydon, he took assembly each day. He wore a gown with a pale blue border, an M.A., from somewhere, but it was a bit of variety from the plain black of all the others except the gym master, even though he had two PhD's.

My first impression, at the inaugural meeting in the Hove Grammar School for Girls had been very favourable. He said he wanted the school to be without the cane, which was very early for that sort of idea in a state school. He had, I think, ideals of proper, tolerant, considerate behaviour, and was good at relating to pupils in that way. I don't think he enjoyed at all being disciplinarian, although he couldn't keep to his no-cane idea. I suspect he was disappointed at behaviour which was more bloody-minded or wicked than he thought proper.

I remember one event when I was in fifth form. That was 1943-4, the first year the school recombined. It was a time when I, with some friends, were talking a lot about religion and arguing in religious knowledge lessons, and forming a distincly atheistic position, which I have maintained since. One of the consequences was that we weren't going to pray in assembly. As we were in the back row we were visible, and were seen not praying by one master, Nixon, not a favourable person.

As the assembly filed out, he came to the back and pointed at me, saying "You come here". He was vehemently angry and demanded a written apology and some sort of punishment. I said I refused to apologise for not praying and would go to the Headmaster, which I did. He listened and said "You realise that I will have to hear Mr Nixon's side," and said he would see me again. Later, he said something like "the important thing here is to protect personality. I must see that your personality is protected, and it wouldn't help that for you to stand out. I must also see that Mr Nixon's personality is protected." In the end, I had to apologise for offending Mr Nixon, but not for not praying.

When we were in the sixth form, he took a special session each week, called Headmaster's class, where we talked about all sorts of things, philosophy, logic, morals, language. We all enjoyed them, and thought well of him, at least, I did.

He also set up a sixth form council, a sort of mock parliament. Some of us didn't think it should be mock, and I proposed, with prearranged support, that the sixth form shouldn't wear school caps. The outcome was that we should wear hats when out, but it could be a trilby. So several of us did- Norman Benbow, Maurice Isaac, Den Peach, John McIntosh, at least.

I was well-disposed towards him throughout, and was stunned by the event of his departure. As far as I can make out, this was in the summer of 1945, when I was in the lower sixth. He signed the report in the spring, but Wheeler did in the summer. One morning during the morning assembly, which included everyone, when it came to the bit for announcements and such, he said that hardly anyone had turned up to support the rugby match on Saturday, and that since this seemed important, and meant that the school didn't care, he was not prepared to tolerate that. So he walked out and never came back.

Well, there was plenty of speculation at the time, and side-talking. I was stunned as it appeared completely out of character, and I couldn't imagine that the spectators at a rugby match mattered a damn. We never found out what it was about.

Getting on the wrong side- or otherwise

The incident with Nixon wasn't the only one. In the second form, I must have been a pain in the neck, as I got 'put on report'. That meant you took a report form around with you to all your classes and in each lesson the master or mistress had to enter a comment on your behaviour. This happened if you got a lot of conduct marks- they were marked in the register and initialled by the teacher. The terminal reports mentioned if you had been on report. I have one which does. The comments from the teachers are not consistently critical of my conduct; so I think it was specific to one or two whom I must have played up or got on the wrong side of. I don't remember antecedant indicents clearly at all, but I can recall this business of producing the report form. Some teachers were surprised and considerate, some cold.

We also got impositions. Sometimes writing lines, sometimes writing an essay (bloody silly idea to make writing an imposition). There was very little official corporal punishment. Some people got the cane. It always seemed to be the same ones; so it clearly didn't dissuade them from whatever it was that instigated it. I and my immediate friends never got it. That didn't mean that there were no actual physical assaults. They were treated as jokes- afterwards anyway. Some teachers were prone to cuff pupils, and that happened to a lot of us including me.

One chap, Swift, then a woodwork master, was a bit physical. I don't mean he made sexual advances, but if a boy said his sandpaper was smooth and no good, Swifty would try it on your cheek, and say 'Is it smooth, then? Get on with it'. He was also the games master for Rugby. Ah, I hear you say, are you sure he had no homosexual tendencies? I didn't say he didn't, I said he made no advances.

He was an economist, and somehow we got to talking about economics and money, I think in the sixth form. He lent me a couple of books, which I kept, not because I neglected to return them, but because he died. It was on a school camp of some sort which I didn't go on. It may have been a harvest camp, in Devon, alternative to the one at Farnham I went on. He was drowned in a lake they used for swimming. I'm puzzled when this was, as his name appears on the 1945 calendar, and I hadn't marked it out. Yet it couldn't have been 1946, after we left. I asked Wheeler, the headmaster, what I should to about the books, and he said he was sure Mr Swift would want me to keep them. I still have them.

Katz was the maths master in the fourth and fifth forms, whom I discovered in the sixth form after finishing maths, to be civilised, knowledgeable and nice. It was he who explained to us what atomic explosions were about, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He was troubled by us in the fourth form. We played him up. We had rude words linked with numbers and used to mutter them when he turned away to the blackboard and said a number. Two (up). Four (skin). Very much 'fourth form humour'. He got annoyed and sometimes threw the blackboard rubber. Must have been awful for him.

Bosustow was quite a nice chap and not given much to free use of his hands. He gave me an imposition once, quite late on, perhaps in an odd lesson in the sixth form. When he asked me what I had written on and I replied 'paper'. I think it was more the laughter in class than the reply itself which made him angry, so he slapped me. I was more offended than hurt, as though the interchange had suddenly switched to a more primitive or childish level. We didn't go in for impositions and slapping in the sixth. I expected he might say something like 'behave as adults and you'll be treated as adults'. Difficult, adolescents must be to teach, though some masters, and mistresses had no trouble.

One lady who took English, we must have had dealings with in the sixth form through the library or a society perhaps. She was sort of unpromising as a handler of late adolescent boys, a bit diffident. But she had no trouble. I first read 'The Grapes of Wrath' on her recommendation. She was slightly embarrassed to warn that it was a 'bit stong meat, you know'. Heterosexuality works too.

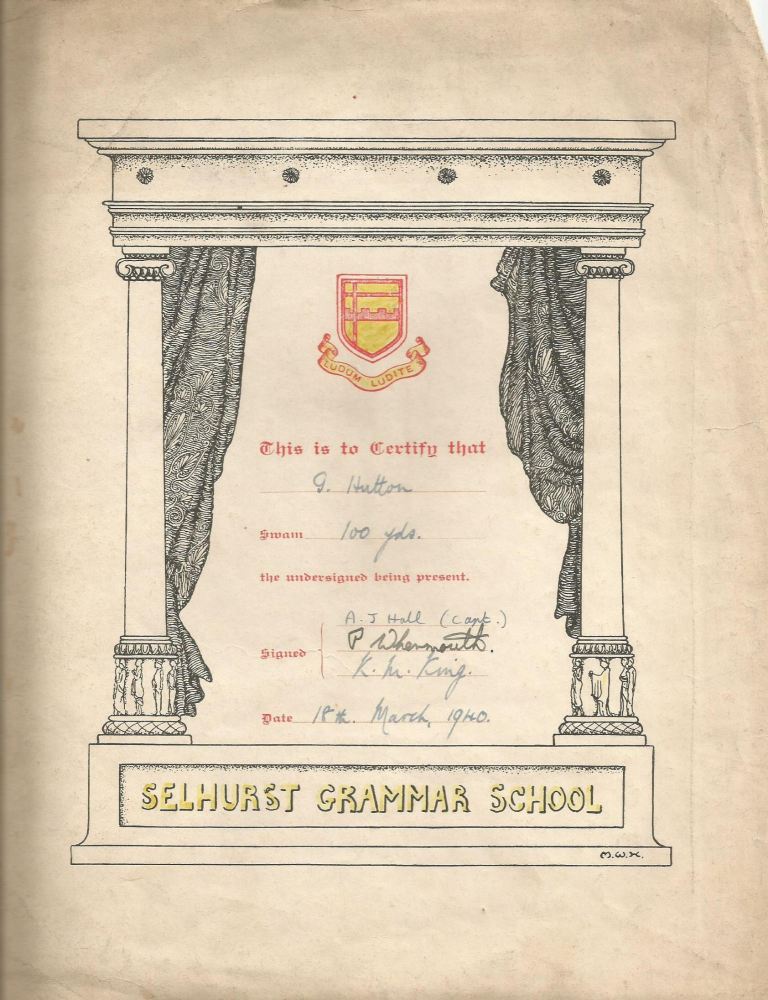

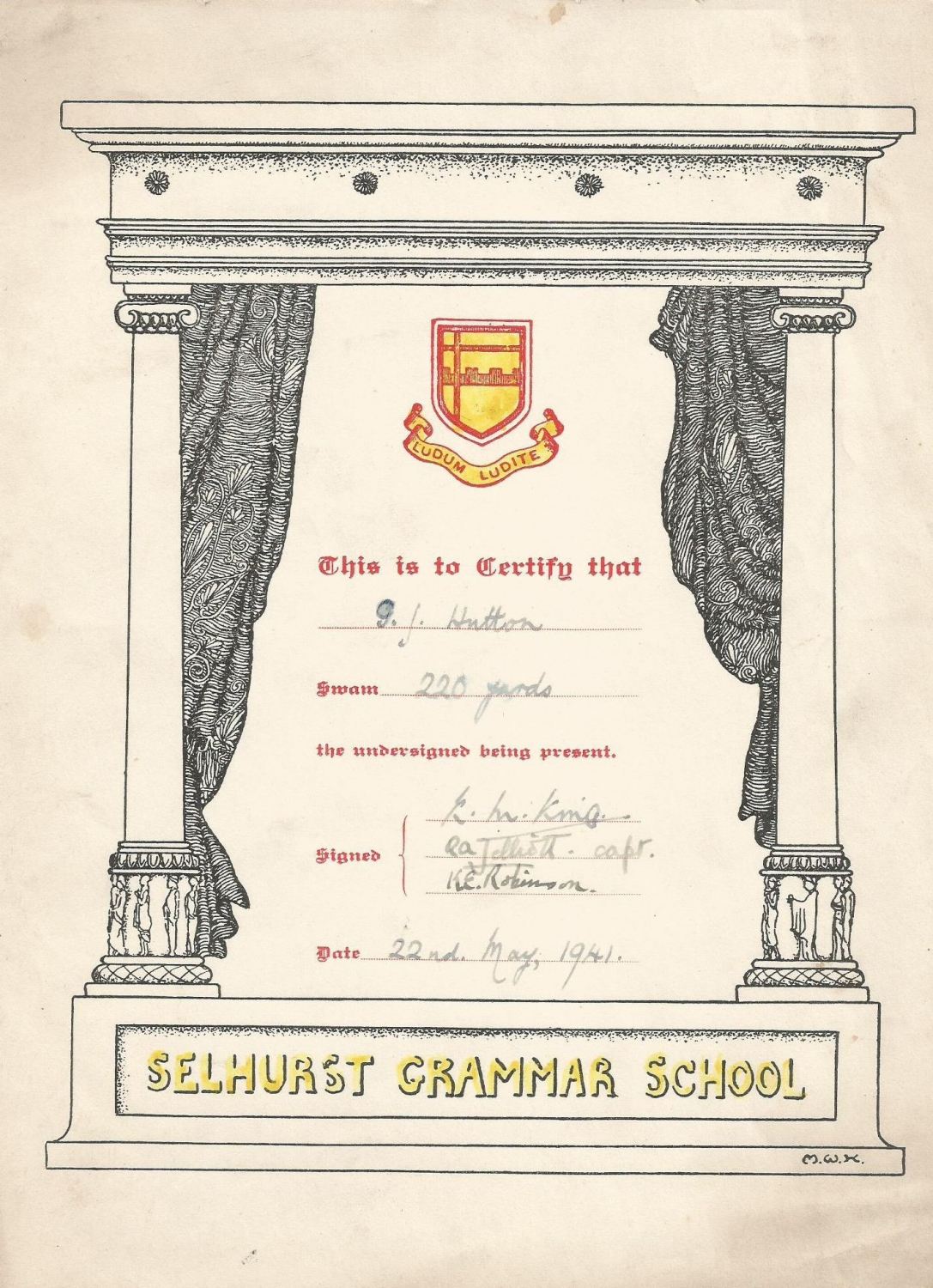

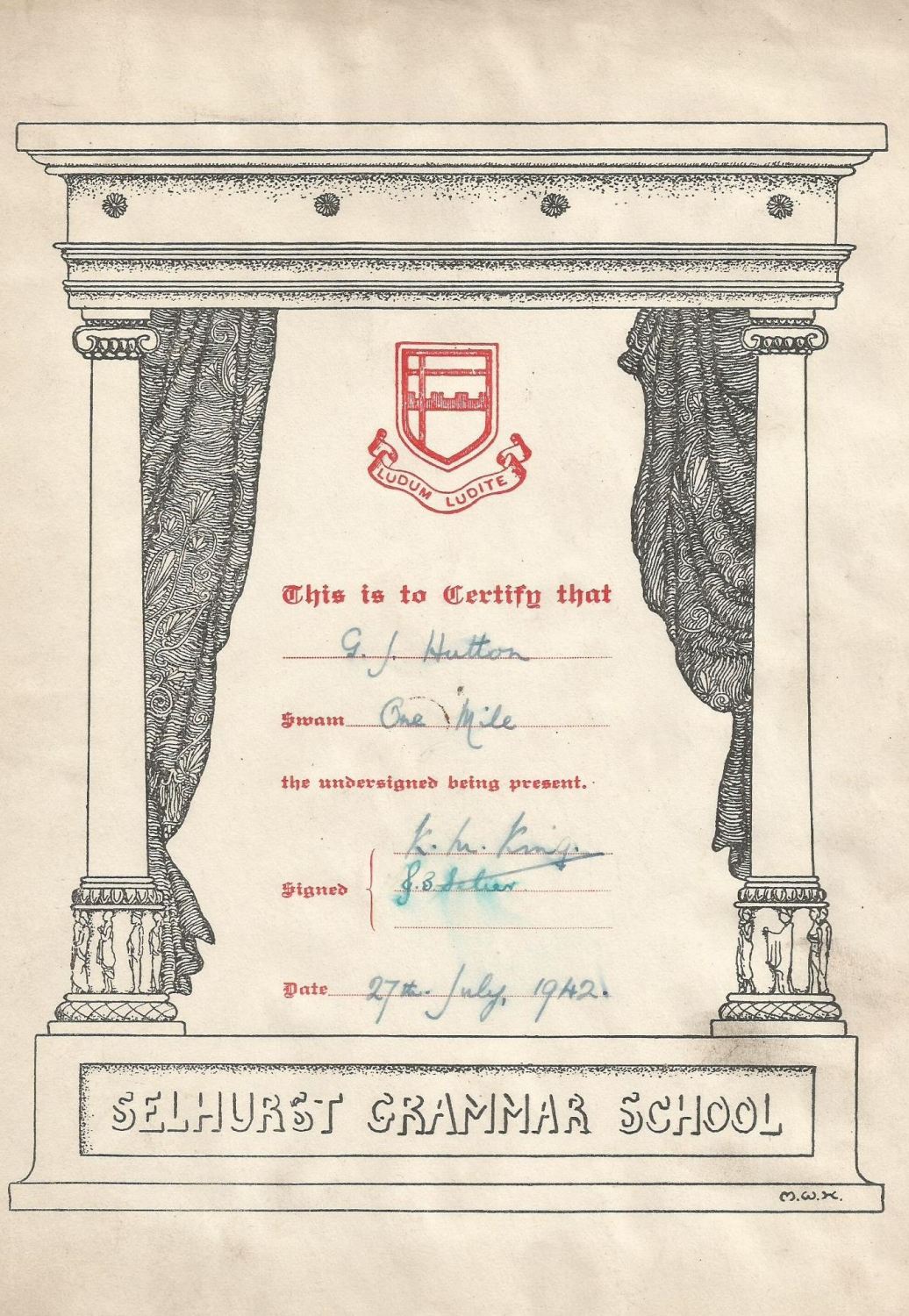

Sport at Selhurst Grammar

Swimming was the great thing for me, but I didn't think of it as 'Sport'. I could swim quite early. I learned at elementary school. My time at Selhurst gave me plenty of swimming and some good coaching. This was from a chap called Ross Eagle, with whom we had training sessions at Thornton Heath baths, after school. He was keen on the crawl, and when we had learnt a good crawl, we were allowed to sport an eagle on our shorts. I got to be swimming captain of the house, though not of the school.

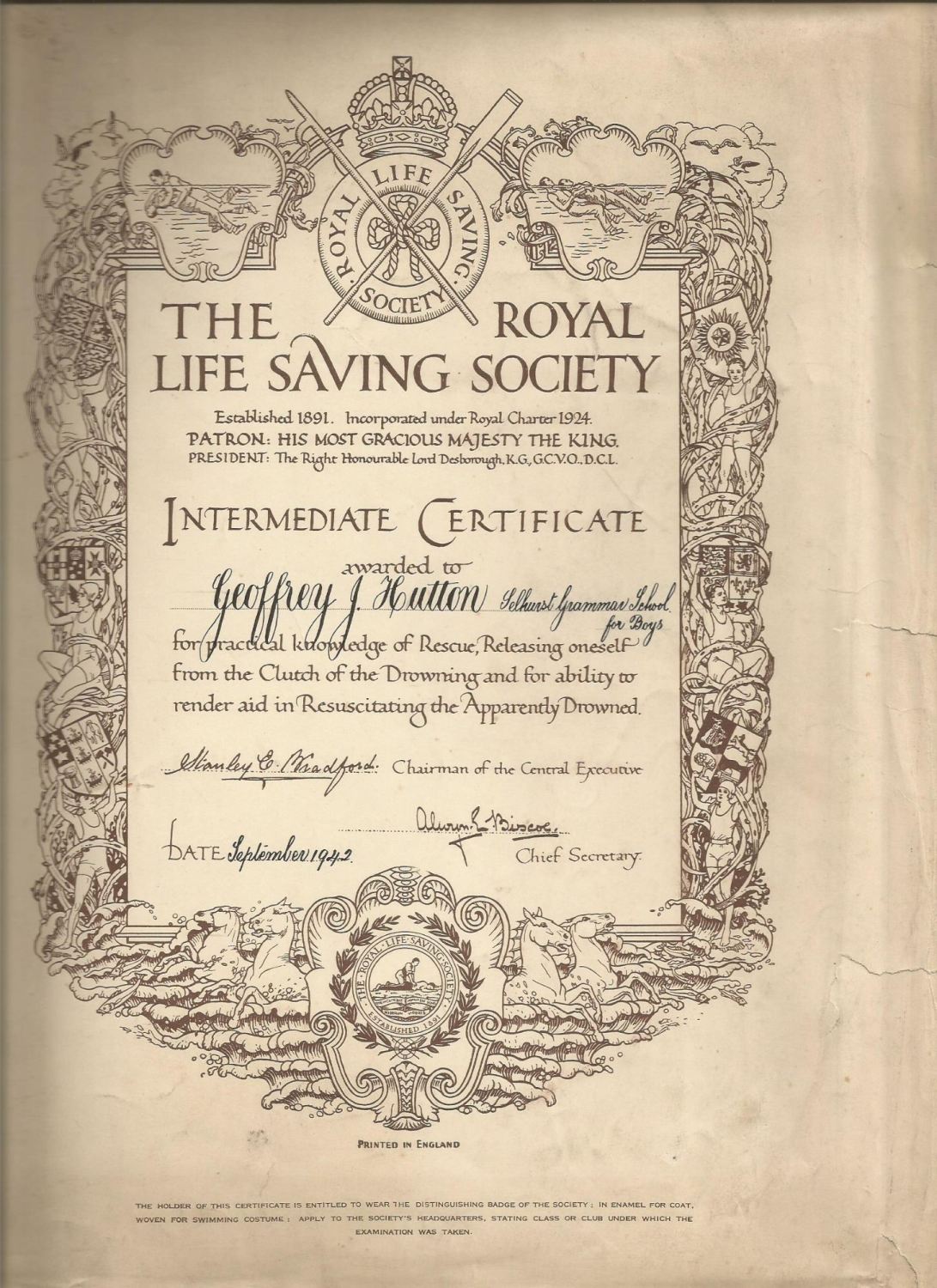

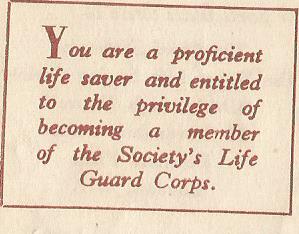

He also took the life savers certificate

I particularly like the wording, 'Releasing oneself from the Clutch of the Drowning...' although not sure how they simulated that. We have his woven badge and this medal.

Here is the card from inside the medal box

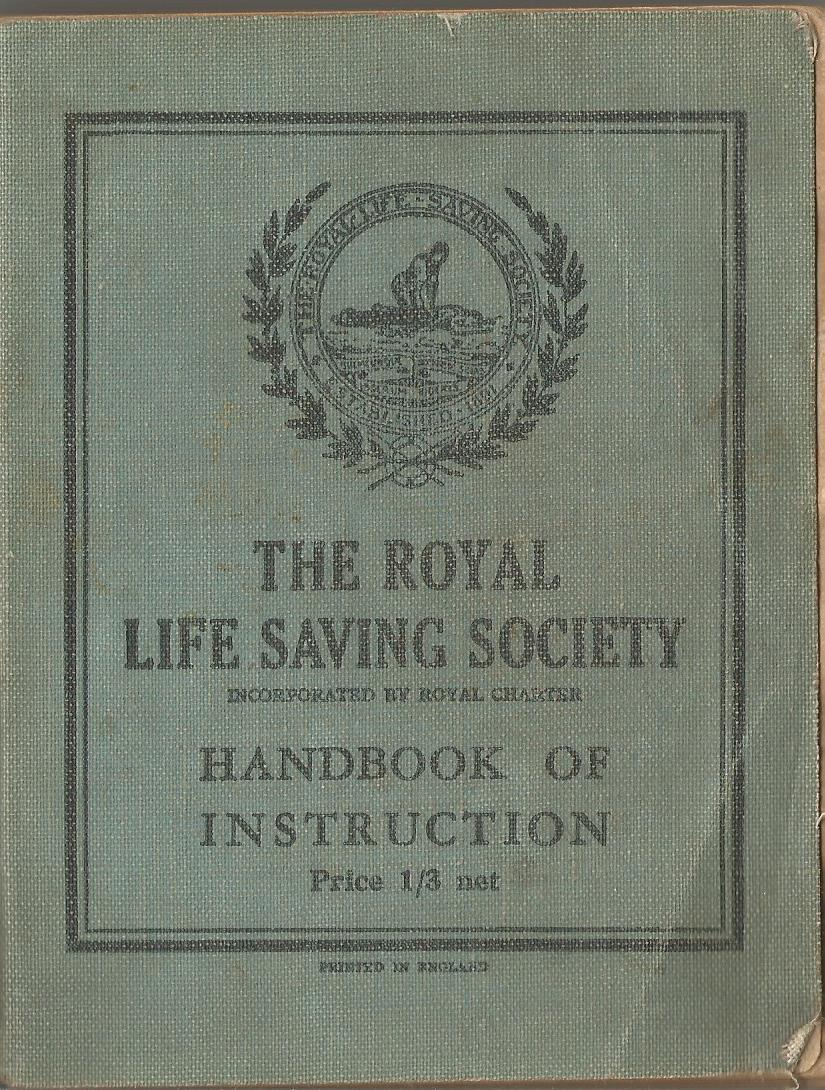

and here is his Life Saving Handbook, published in 1937.

Rugby

I didn't know that he had ever played rugby; he kept that quiet, but below you can see him in the 2nd XV 1945-6.

Nothing much good about sport. Cricket was boring, I couldn't catch the ball and couldn't hit it very often. They used to put me in at long stop or deep field or some position well out of the way of the action, such as it was.

Rugby was a little better. I used to play in the school second fifteen, as a foreward, front row left. Forewards are big beefy blokes, especially front row. I wasn't, but I couldn't run very fast, or catch balls very well, so I was more out of the way where I was, in the 'pack'. When we had scrums I was 'loose head'. The front row consisted of three players so one player- the one on the left- went on the left of the opposing right hand player, while the others had their heads between the opposite ones. It was more comfortable being loose head. The middle one was supposed to kick the ball with his heel - 'heel' heel' was the cry. This all worked well, except one school which insisted on doing it the other way around, so there was always a tussle to see which lot would get their way. Sometimes I got my ears squeezed.

There was something nice about wearing the boots, which were made of soft leather with big leather cones or spikes attached. They gave a good feeling of being able to fun fast, especially on slippery or frozen ground. It wasn't much fun tackling and falling over and all that.

and the back...

Selhurst Grammar School Calendar for the school year 1940-41

Selhurst Grammar School Calendar for the school year 1942-3

Languages

During this period of my life, I developed an interest in language, and language differences. Most of the language interest came, I think, from school, but somehow by the side of the formal teaching. We learned Latin, and I was good at that, but gave it up after the third form, as I opted for science alternatives. I can remember laboured attempts to translate. The same experience with French continued for a couple of years more. These are not the basis of my continuing fascination with words and meaning, changes in meaning, differences between langauges, and similarities between them, pronounciation and dialect.

Music

Musical interest didn't start in this period, but school gave me some useful and enjoyable additions to what I took from piano lessons, and above all structure, as in sonata form, and what symphonies and tone poems are. Mr Scott was the main music teacher, as well as Latin. He had written the school song- in Latin, of course. Io Selhurst, silva felix. Get it? Sel (A.S. silly=fortunate) hurst (wood), thus silva (wood) felix (fortunate).

We had a musical society where we listened to records and such. I think it was through that I was encouraged to try the clarinet. I liked Dvorak 9th, though in those days it was the 5th, and in particular the cor anglais solo in the slow movement. A clarinet was the nearest I thought I could get.

I managed to buy one with my saved up pocket money. I think it was about the fourth or fifth form. I remember it cost £3, from a second hand shop near the school. The shop had all sorts of things in it, including odd musical instruments, like fifes and concertinas. The shop owner seemed unaccommodating, or intimidating, but perhaps he didn't like adolescent schoolboys. Anyway, he let me take the instrument to get an opinion from Scott.

I phoned him up and went to his house, one Saturday, probably. He was a neat gentle sort of man. His house was neat- one of the 1930's semi's locally in Norbury. In the living room was a clothes horse with neatly ironed shirts. I remember that, I suppose, as it was another personal side of the teacher in role. He said the clarinet was alright but did I realize it was in C, not in A or B flat and was probably, therefore, a military band instrument. It had the Albert system of keys- very simple and out of date.

I tried to learn it, but it didn't get on too well. Scott suggested I played in the School concert that year. So I learned the cor anglais solo from Dvorak's 5th/9th. The problem was that I had to transpose it from D flat to D, and forgot to tell Scott, who was accompanying on the piano. I came in a semitone sharp. He was unperturbed, and shifted key immediately. I have seldom felt so embarrassed.

In the later years of school, some of us got interested in singing part songs. This was again encouraged by Scott, and coached by him. Swift, the rugby master, told us about a very good choir indeed, called the Fleet Street Choir. I thought that one day I might like to get into it. By the time I did get interested in joining a chorus, in my mid-twenties, the Fleet Street Choir was no more and I had forgotten about it anyway. It was the Dorians I joined. Two of the tenors had been in the Fleet Street Choir. At school, Maurice, Norman and I, with one or two others, possibly John, learned some part songs, and when we went on our walking tour of the lakes, we entertained others in the youth hostels with considerable effect. 'Drink to me only with thine eyes' in four parts was our piece de resistance. Barber shop quartets? They had nothing on us.

Harvest Camp

The war and school came together in the harvest camps. There was a labour shortage on farms, and much attempt to increase food production. So we went on harvest camps for a few weeks at harvest time. I must have gone on at least three, one at Down in Kent, at least two at Farnham in Surrey.

Anyway, they were great experiences, and we went back again in spite of the hard work and some nasty farmers. The Down camp was quite small and wasn't a camp, as we slept in the little school hall. The Farnham camps were proper, with bell tents and ridge tents, and camp beds for all. The work was allocated daily to squads made up for the numbers required. Sometimes a lorry would pick us up, but usually we rode our bikes there.

Geoff took these two pictures at Down Harvest Camp, 1943.

I preferred the corn harvesting, like most of my friends. What we mostly did was stacking or stooking- picking up the sheaves cast by the reaping machine, tying them with a twist of straw, and piling them into stacks or stooks. They were stooks in Down and stacks in Farnham, or the other way round. Sometimes we got to work on the thresher, throwing the sheaves up to the top hopper. Heavy and dusty, that. And we thought, with the tractor-drawn reaper, or fancier, a reaper-binder, and with the mechanical thresher, that we were highly mechanised. Not like the old days the old workers remembered well, hand reaping and threshing. Never thought of combine harvesters doing the lot.

We also did quite a bit of other cropping, digging potatoes, turnips and such. That was back breaking work, especially when it was hot, as it was, especially 1945. Tough market gardening work, and a farmer with a reputation as a slave driver, made for very unpopular postings.

We didn't work in the same way as farm workers. There were still a few older men around. Either, they or the farmer showed us what to do. We could see, especially with the digging up, that the older men worked very slowly, but they kept on, and on, and on. We worked in bursts with all sorts of stops for singing or resting. There was still a lot of work done, in spite of complaints from some farmers that we wasted time, and it wasn't worth having us. Others were friendly, and showed us what to do, and encouraged us. Guess who we worked best for.

A whole field of potatoes or turnips is an intimidating prospect, and several days at it was boring and tiring. Apple harvesting was a joy. There was one big orchard we went to, where we were supervised by one old chap who let us eat apples. Worcester Pearmains, they were, and put up with a bit of larking about. On the last day he let us take some apples, which we put into our saddle bags. The foreman saw what was happening and made trouble. He made us unload, and he weighed the apples, laying off about the cost and laying into the old man. We were furious, but there was nothing we could see to do, except what we were told to do. We tried to say it was all our idea, and not the old man's fault, but I don't think it had much effect.

The camp experiences were enjoyable; the open air and being in camp, and also because of the changed relations with the masters and their wives, if they came. The catering at Farnham was done by Mrs Barlow, and helpers. There weren't many staff there, and I can't remember what they did. They didn't come out with us working, so I suppose that apart from the planning, official contacts and work scheduling, they must have been helping around camp.

Of my set of friends, Maurice, John and Norman came to these camps. Den Peach didn't I think. We determined to hold a midnight feast, which went slightly wrong in the cooking, as someone had picked up soap instead of margarine. Great giggles. Not that there was a lot of difference in those days. We composed a camp song, as well as singing the Red Flag, frequently. Something on the lines of 'We all came down to Farnham, for to get the harvest in'...On Mrs Barlow's cooking, we're getting rather fat'...and so on.

The Farnham camps were set up in Farnham Castle park. It was very near the town, and we had plenty of chance to go into town. A nice little town it was then. The people in the big house visited and must have helped in the setting up. On the way from the park to the town there was a newsagent where I used to pick up a Sunday paper. I discovered one I had never heard of, and tried it. All newspapers were six pages, and this one had so much more information, and such sensible comments, especially on politics, that I determined to take it. The Observer. Pity it's a proprietor's rag now. Geoffrey took this paper weekly until his eighties. Reading the Observer Magazine on Sunday at breakfast was part of our youth!

Selhurst Grammar School Calendar for the school year 1943-44

Scouts

Before the war, I was in the Cubs, the 42nd Croydon, run by Miss King, who was the sister of 'Smiler' King, a history master at the school. After I came back from Brighton, I was of Scout age, but I think the 42nd Croydon was defunct, because I went to the 1st South Norwood. This met in a hut which I am sure I couldn't find now. It was down some lane, on waste land, or most likely railway land the other side of the big Selhurst sidings and junctions.

I got to be a patrol l leader, and took it quite seriously, although I never read Baden-Powell's Scouting for Boys. I think I was a squirrel, and we had grey and maroon colours, very pretty. I took all sorts of badges, [which we still have] including, of course, swimming and first aid, music and cycling. We went on short camps and hikes. I think the old small back pack I have dates from that time. I had a nice pole, or staff, carved with symbols denoting badges, rank and nothing in particular.

I think I enjoyed it, as I kept it up for some years, but I really can't remember just when it all was. Anyhow, I know why I left. King decided to start a troop at school, to balance the inevitable and popular cadet forces. He asked me if I was interested, and I agreed immediately. The chap who ran the 1st wasn't very pleased, but I tried to put it as a case of first loyalty. I remember very little of the school one, and I think I must have left as exams came nearer.

Smiler was a nice chap, not at all the althletic hearty type, more your cultivated, knowledgeable potterer. He looked more French than conventional English, with a little ginger goatee beard. He remained good company later. He lived in the Crescent with his sister, who apart from running cubs earlier, kept cats. Rather a lot of cats. Dad used to complain of the cats when he had jobs to do in the house. I don't know how Smiler stood it. But he was an amiable chap. The chap at South Norwood just liked getting out and about, I think. I can't recall why he was there, as I would have thought he was of military age.

There was only one encounter with a chap who had less innocent or less latent tendencies. He was some sort of assistant, and invited me round to his house. He had the room rather dim, with light curtains, and wanted to show me some pictures. I showed no interest, and he didn't push the point, if you see what I mean, but the atmosphere was what you might call steamy. Didn't have any more to do with him. That was early on, so probably when I was in the 1st South Norwood.

Girls

The shift from fantasy to curiosity to experiment was gradual and mixed. I still regret that the temporary bit of co-education in the first form didn't continue. For us boys, it was a matter of finding the girls out of school, even if the girls' school was next door.

Selhurst Grammar School for Boys and Selhurst Grammar School for Girls were mutually out of bounds, but there were ways. Of course some of us knew the Girls' building from 1940. The biology labs ran alongside the playing field which was used by both schools in turn. We could train the light mirror of our mircoscopes and readjust the focus so we got a close up view- at least I think we did once or twice, but the absence of any microscopy results would have been noticeable if repeated.

It seems now like two parallel developments- sexuality and girls. Not that the business of girls was not sexual, but the fantasies, the indulgence in dirty jokes, the joy in dirty songs, even if they referred to women, were about our being boys. That sharing of the puzzlements, the excitements, the curiosity, was easy in a boys' school.

The first girl I went out with lived in Thornton Heath. I think the word was around that she fancied me. We went to the pictures once or twice, but nothing came of it. Pearl, was her name.

The coterie I was mostly involved with, and which included both boys and girls, was around Addiscombe and the dances on Saturdays at Shirley Parish Church Hall. We had hops, not discos. The hop at the Church Hall was ostensibly organized by some sort of young peoples' guild, but you didn't have to join it. Then there were some bike rides at weekends.

At the dances, I came to fancy several. One responded, again through intermediaries. That was Jean Woolston. I gradually got to know her as we went out- pictures, of course, and bike rides at the weekend, with other couples- John MacIntosh and Shirley, who became his wife. Three years after leaving school I married Jean, after I was out of the army and she had left nursing.

By the upper sixth we were mostly paired off, though there were shifts. Sexual activity was extremely circumscribed, and there were no pregnancies that I can recall. We talked, and fondled and that was about it.

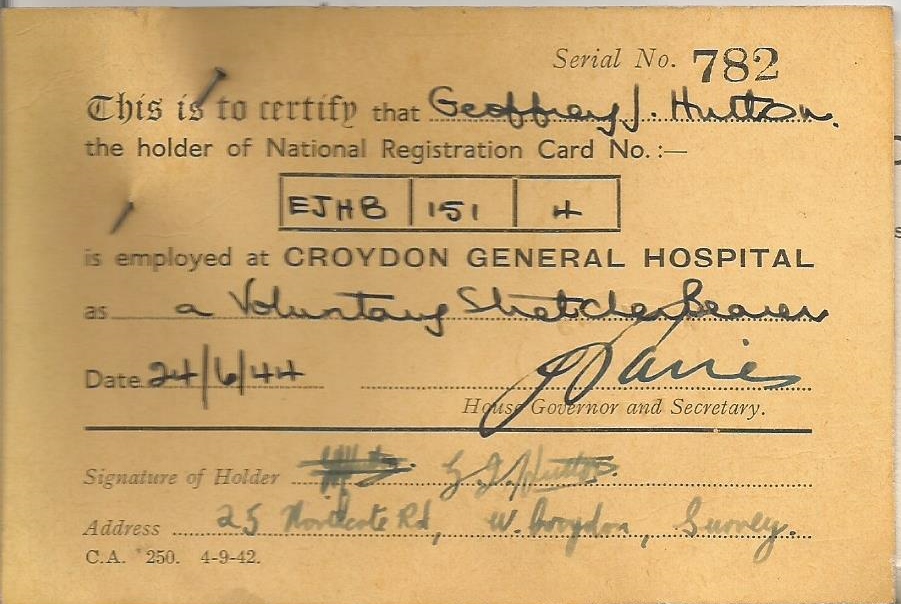

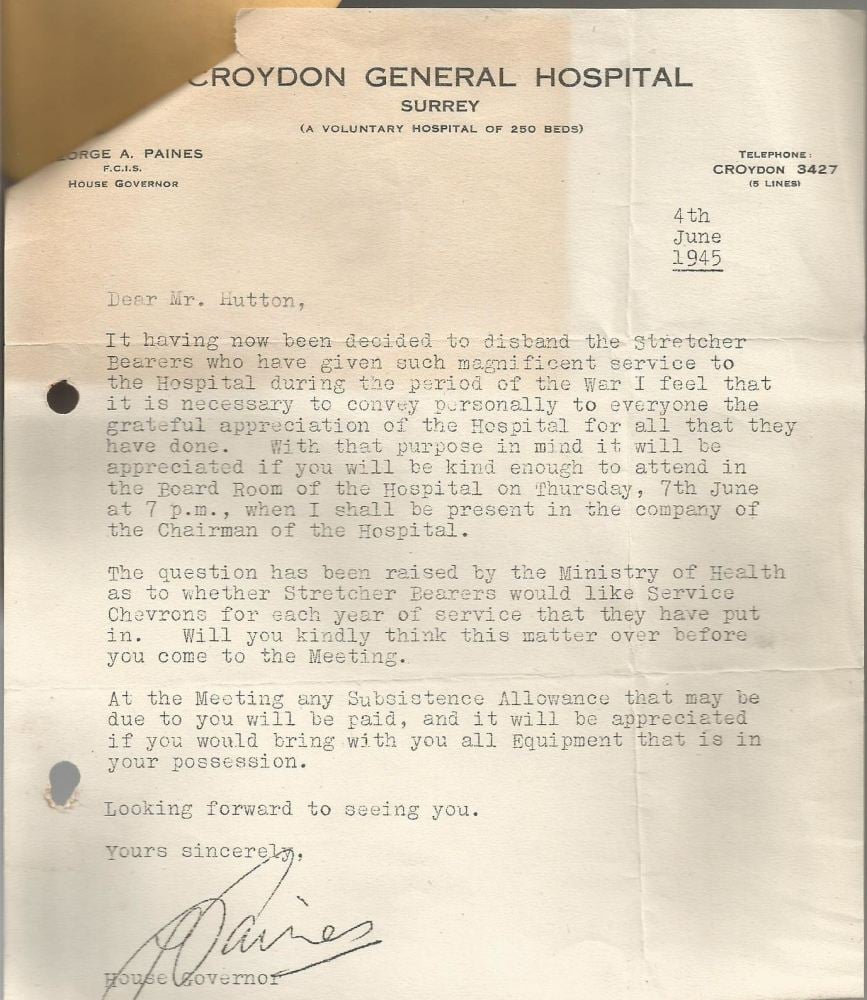

Stretcher Bearer during Croydon Air Raids 1944

1944 saw a new enemy action, just when we thought such a thing was past. V1's, or flying bombs. The sound was characteristic and unforgettable, like a sort of two-stroke engine, not too steady, and quite slow in its pop-pop. The unsteadiness added to the apprehension that it might stop, as it did that when it ran out of fuel. When one did, the silence was itnense, as if everyone was holding their breath, as many surely were. After a few seconds, perhaps as long as ten, which is an age, came the bang. The bombs were mounted on a small craft with a jet engine. Timing it with the fuel supply wasn't a very accurate form of aiming compared with a cruise missile, but it did a lot of damage.

They mostly came over during the day, but not all. This was the time when some of us at school were acting as stretcher bearers in Croydon General Hospital. I went on Fridays after school, with a couple of others. I'm not clear who they were, although John MacIntosh was one. Sometimes we got to sleep a bit, especially after the raids stopped, as we were often then used more like night porters to move patients between wards or take up emergency admissions. It was busier when the V1's and V2's were active.

Those events gave me my first direct experience of death and of severe physical damage. Some casualties were dead on arrival. Others looked as though they should be. One night a chap who held some official position in the hospital was brought in after a V2 rocket landed near his house. He looked peeled, and I think he was dead then or soon after. Unconscious and dead people are damned heavy.

When we slept, we sometimes had camp beds in the gyny clinic. The cockroaches were almost unbelievable. Switching on the light in the night produced a clearance of a practically black floor in a couple of seconds. I never worked out where they all went to.

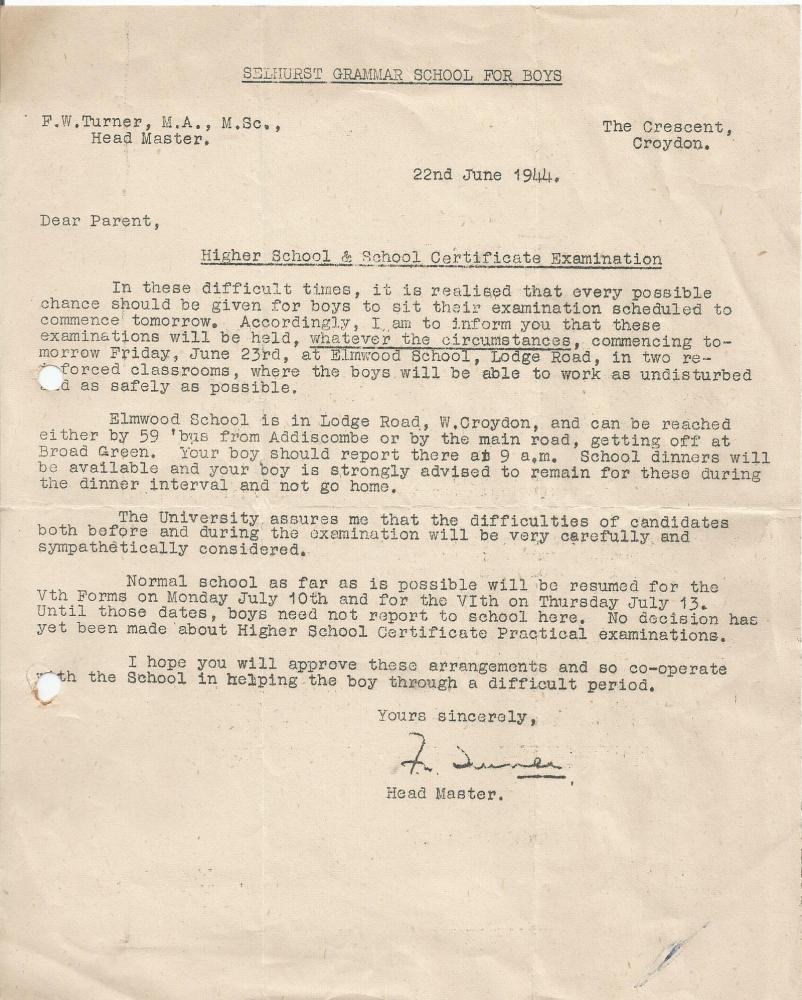

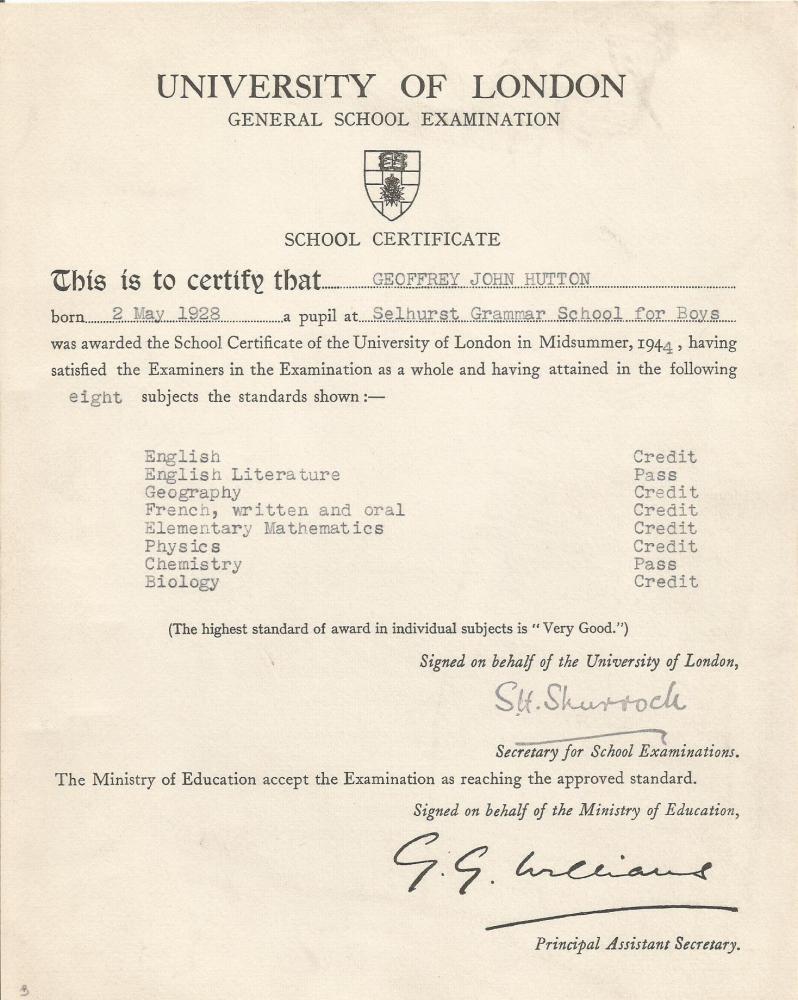

This was the summer we took General Schools, and the reason why we sat the exams in another school, Elmwood, in a reinforced classroom. With these bombs, there was no alert, and no all clear. Not until the armies moved up the coast of the Low Countries, and to the Baltic coast, and the launching sites of the bombs were taken, was the threat removed.

The sound of the all clear was a relief. The steady tone. The alert began the same, but after a second the tone dropped and then oscillated. The anxiety it generated was brought home to me in more recent years when various radio or television programmes have used the alert in a story. My heart still responds by tightening, although with repeats it is lessening.

General School Certificate from 1944

Letters

The war was never long out of mind. There was always the news in the papers and on the wireless. The news largely consisted of reports of it, and there was always something going on which was saddening, disgusting, hopeful or triumphant. In my own direct experience, signs of war were all around us, not only from the enemy action, but from the blackout, the shops, the people in uniform. Occasionally though, we got letters from my brother when he was in Africa and Italy. Although they were of course censored with blue pencil, so anything like war reporting was out, they gave a feeling of contact quite different from the news. Whatever the contact, the change in approximate place of origin was like a story, even if the official address stayed the same all the way- something line of supply, 8th Army. Long lost, but wouldn't they be interesting now nearly fifty years on.

VE and VJ

The end in Europe was expected, as the news told of the inevitable progress to the German collapse. The announcement of the surrender was almost dreamlike. The war was over. Celebrations started almost immediately, though muted for those who had people in the Japanese theatre of war. I didn't know anybody who did, but my friends and I were coming up to eighteen and expected to be there ourselves in a few months. We had no idea, of course, of the impending atomic bomb and Jap surrender by November. Meanwhile, it was May, the weather was lovely, and there was a big get-together in town, and at Fairfield, a field then. Everybody seemed to be out, everybody greeting everybody, singing, laughing, hugging. The only medal I have was issued by the County Borough of Croydon for the victory celebrations later on 8th June 1945.

VJ was a repeat, and had the quality of finality, though not the quality of initial spontaneity of VE. So we expected everybody back, and the new world to begin.

There had already been the 1945 election with the Labour landslide, and the widespread feeling of the need and the prospect of doing things better, with Beveridge, full employment and nationalization, which appeared like doing away with the failed, exploitative private ownership of steel, coal and transport. Above all, the National Health Service.

I had campaigned for Labour and I joined when I could. There was much debate at school about the election, and I and others wondered which party to join. There wern't many Conservatives, and one, Bishop, was so appalled by Churchill's speech when he warned that Labour could only govern with a gestapo, that he changed to Labour. I seriously thought about the Communist Party, and a new one called Commonwealth, but in the end settled for the main stream, as it were.

We knew we would still be called up, though not to fight, now. One of the masters, Hughes, who was the physics teacher and the form master for Upper VI Science, said to me that the army might be good for me if I wasn't too cynical. It wasn't good for me, as it happened, and I don't think it was cynicism, but that was one of the remarks one remembers of someone taking an interest in who you were.

There wasn't an end to war though. Already the Greek Civil war was on, and a lot of debate about what we were doing fighting for the monarchy against the Left. And there was Palestine. One of my friends, Heartfield, lost an eye in a bomb attack in Palestine.

But that is another story, and it feels like another phase of my life, an interim phase before my twenties, of waiting for call-up during the latter part of 1946, and of time in the army.

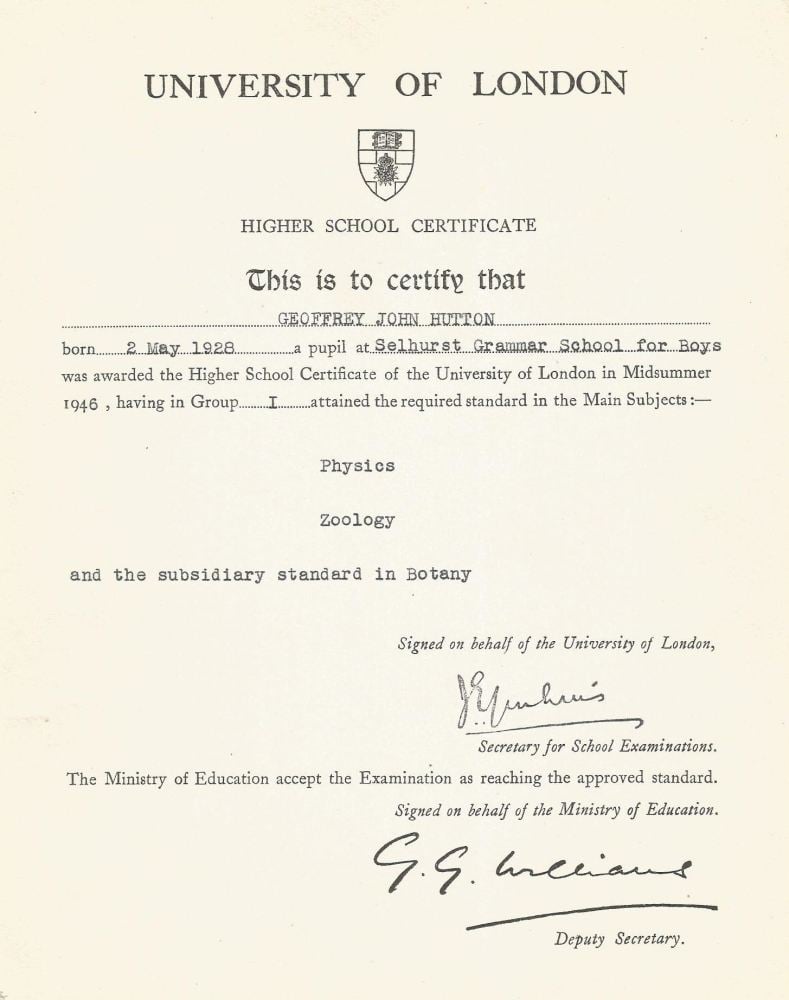

Higher School Certificate 1946

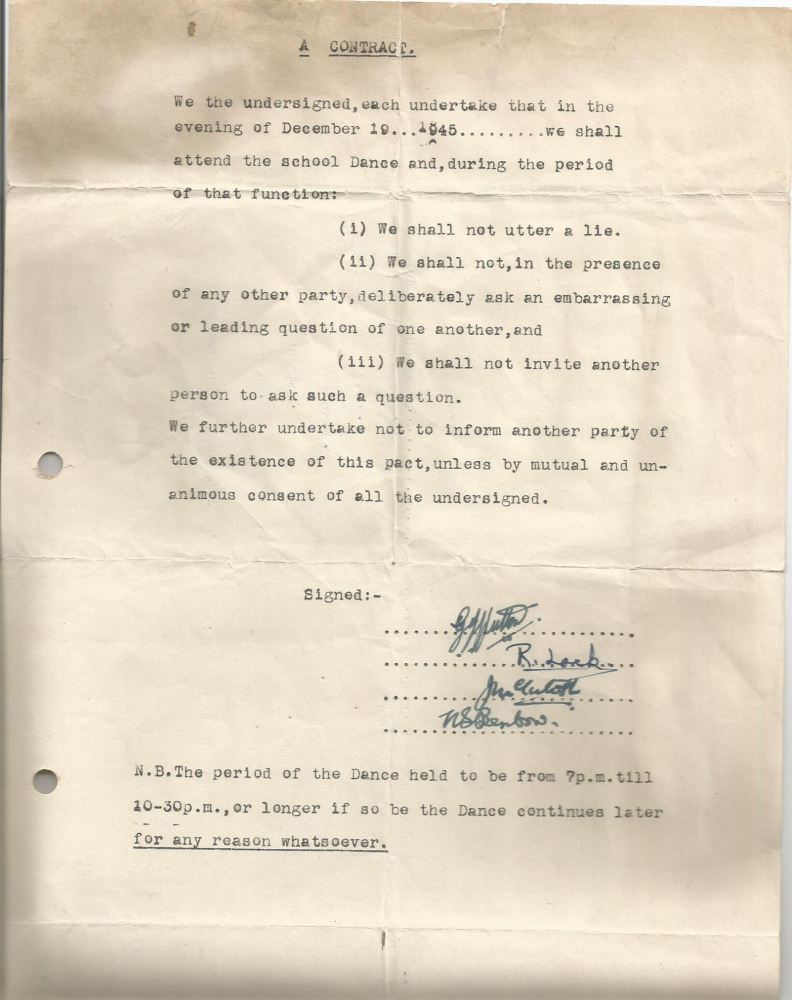

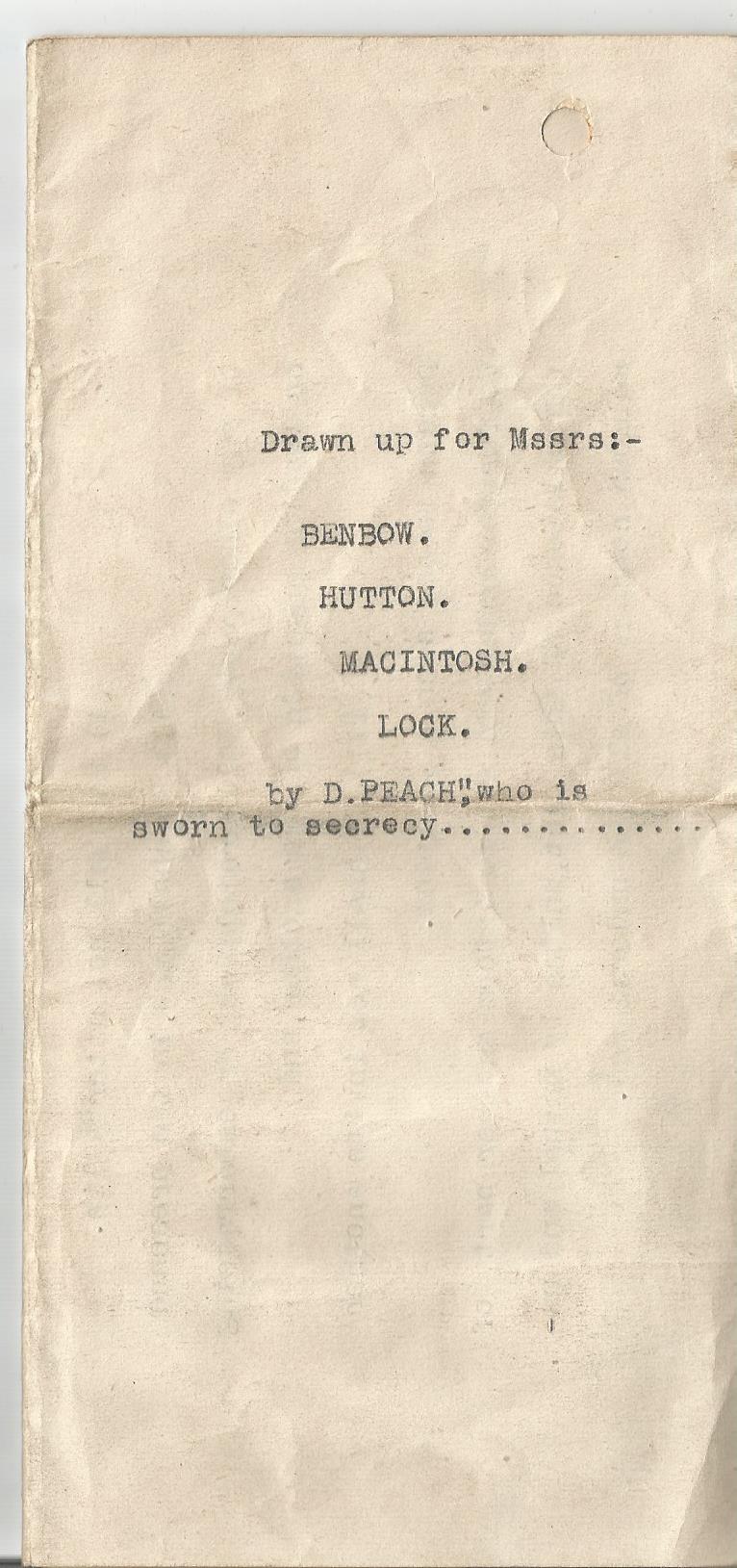

They did have some fun though, and here is a little peek into what they got up to.

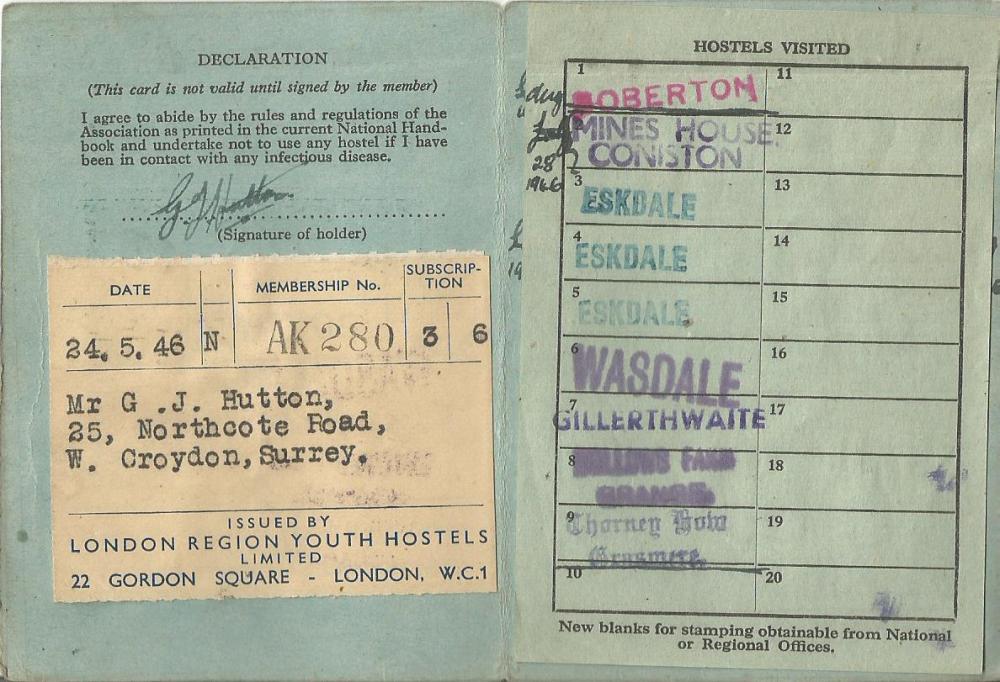

Prefects

Norman (Ben), Maurice (Icsy), John, Den, and Goldhawk formed my immediate group. The others in the group were more prominent in the school than I was. Maurice was school captain. John, Den and Ben were house captains. I was vice captain to John, and house swimming captain. But they were all senior prefects, and I was only a junior. Something was said about the second form 'on report' business. It's also true that I wasn't any good at games and athletics and that seemed to count. On the other hand, I had been form captain for a couple of years. Anyway, I felt a bit put out, that in some way or other I was an inferior. I'm not sure in retrospect that this was felt by the others.

The aforementioned boys are all amongst the prefects here who faced being called up to WW2 before they finished their schooling, as the students in the years above them had been. It must have been terrifying. They were lucky.

Geoff is in the back row, second from our left. George Bray, who wrote his own account of life as an evacuee in Brighton, stands beside him.

and here is the back...

Schooling ends

There was an important interlude from the time of leaving school until I was called up to the Army. I left school in July 1946, and was not called up until December 5th. During that 5 months, my male friends were called up one at a time, so the group shrank gradually. We used to meet each other and the girls frequently for one thing or another, including regular Saturday morning at Wilson's coffee house in Croydon High Street. This was a rambling shop, with corridors, little side rooms and bays. Somewhere or other everyone turned up during Saturday morning. It was a marvellous setting for talk, getting to know, talking about, flirting, dating. I began to cycle over to Addiscimbe to see Jean, until in September she went off to begin nursing training at King's College Hospital. By then we had become quite serious, and were talking of marriage.

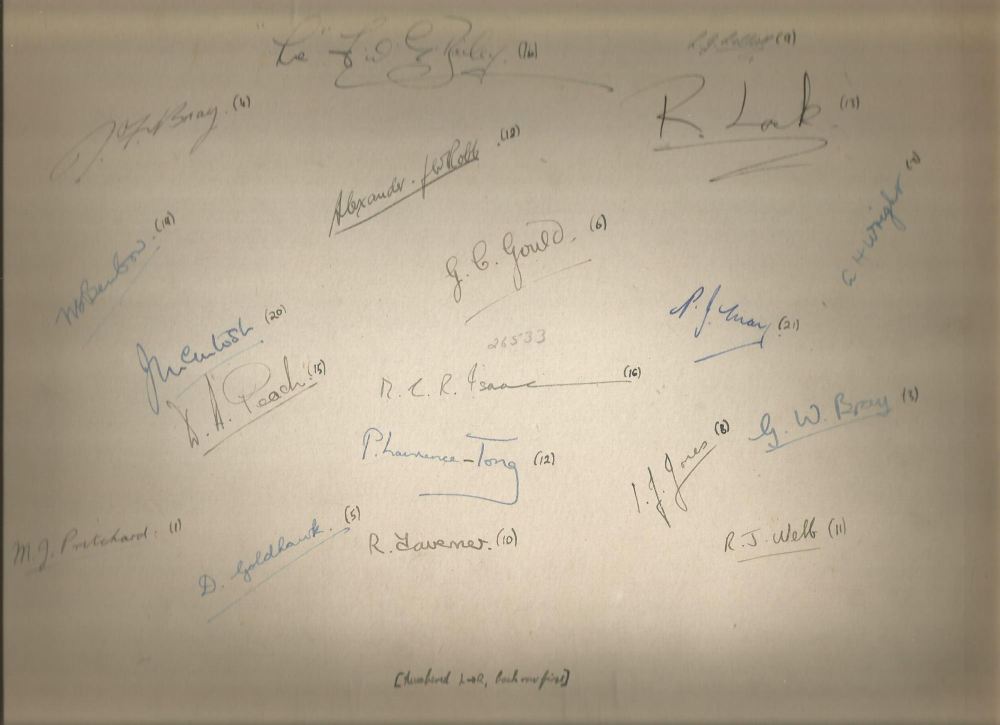

In September, Norman, Maurice, John and I went on a walking tour of the Lakes, with Goldhawk, who had joined the sixth form from John Ruskin School. We took the train to Coniston, and walked around the south west corner, Ennerdale, Wastwater and such. It was all enormously enjoyable, and the scenery captivating. Even the day taken off to allow blisters to heal, was delightfully spent by a little lake above Ennerdale. We stayed in youth hostels, which were really for walkers then. See picture on the homepage.

Some of the more remote farmhouse ones were on the rough and ready side, with earth privies and such. For two or three nights we had to split up because of accommodation shortages. I went with Goldhawk, who was a nice chap and even though split up, we all enjoyed ourselves.

During this spare time when I followed up some of my interests I had developed. In particular, I studied philosophy, quite a lot, through two books of C.E.M. Joad, whose lectures I later attended. Through this, I came to see that my position on religion was best described as sceptical atheism.

I met a chap called Raymond Winch, maybe at the library or something like that. He lived in South Norwood, and was already at University College London. There were some who got to go to college before they were called up, but I don't know if he was exempt on some grounds anyway. He was interested in philosophy. He was an exuberant, eccentric character, and I enjoyed his company for a while. He lived in a big Victorian house a couple of turnings beyond the Crescent, where he had a study chaotically piled with books and papers. I think he became a professor of philosophy.

It was he who introduced me to UCL, by taking me up one day, and inviting me to a Debating Society Foundation dinner. I see from the menu that it was March 1946, so this contact predated my taking Higher Schools, as it happens. The toast to the guests was replied to by one Hugh Gaitskell.

We also went on a weekend trip to Cambridge, to look around. We stayed in a youth hostel on the way, I think in Thetford, and visited a monastery nearby. Winch was a Catholic. It was the first time I had visited such a place since Buckfast Abbey when I was a little boy. Now, a sceptical atheist, I was both slightly shocked and delighted when one monk to whom we were chatting while he worked in the garden, said he " couldn't think what the Lord wanted with a wicked old bugger like me." But He did. I was quite impressed with the place and its atmosphere.

That was the end of this phase of Geoff's life.

On the next page, call-up and National Service in Germany awaits...