National Service - British Army of the Rhine 1946-48

Call-up for National Service

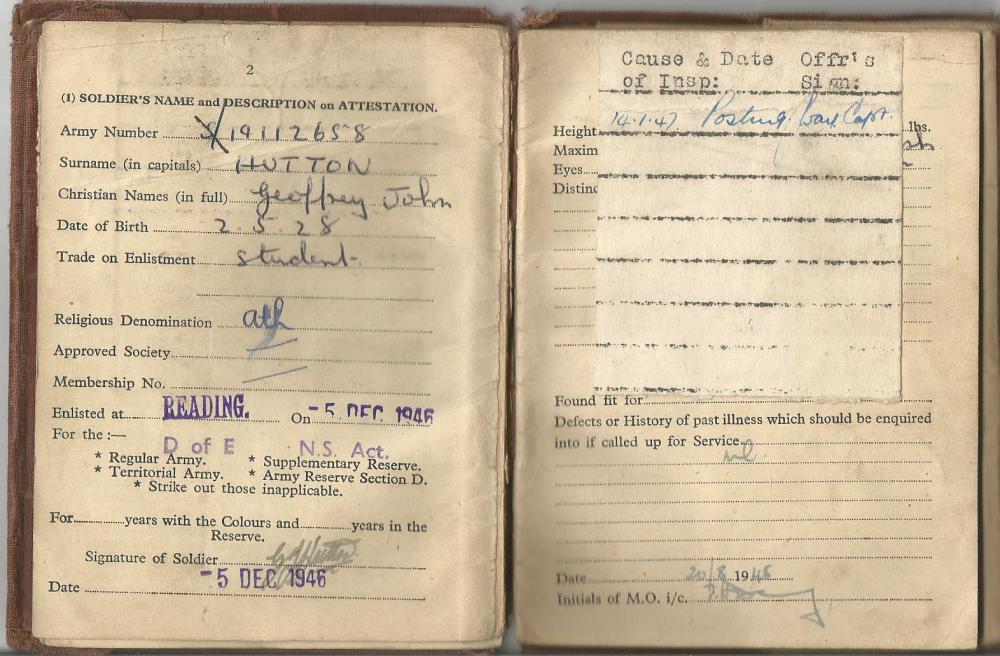

Was on the 5th of December 1946, at Reading. The actual joining took place in a big town hall, with tables down one side, at one of which details were taken down. "Religion?" " I don't have one" "Atheist then?". And that is how it came to say atheist on my dog-tag, the brown fibre disc inscribed with name, number and religion which we all had to wear on a string round out necks. The number was used so much it's difficult to forget. When asked 'name, rank and serial number,' we usually gave just the last three numbers. We were also given age and service numbers. This was the number of the batch we would be in when demobbed. There was no fixed period for national service men. We were enlisted for the D and E- duration of the emergency. We were still formally at war. Each week or month a batch of people were released and there was a lot of guessing of how quickly it was when your number might come up.

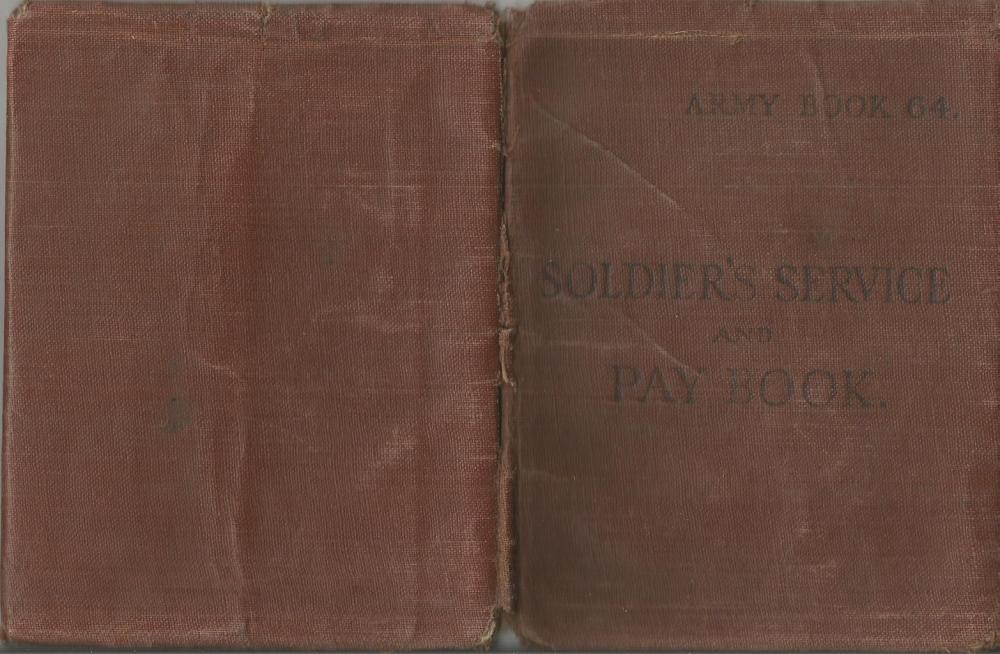

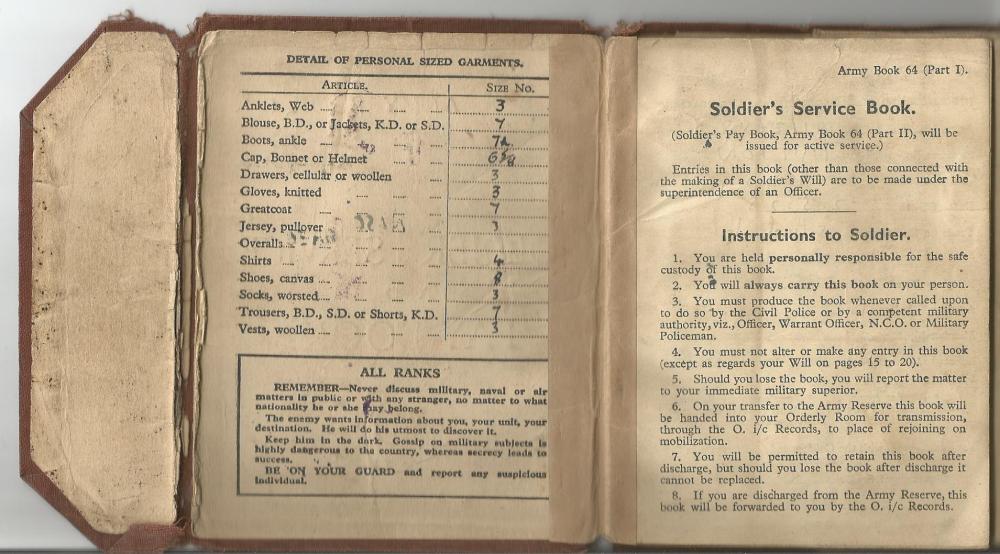

We were fixed up with a pay book, and then to the stores for kitting out. Uniform, underwear, socks, webbing. I expect they give them pyjamas now, but not then.

The barracks room held about 30, with a corporal in charge. We soon got to learn about the bigger formations, and higher ranks, but I get a bit muddled about them now. Serjeants didn't live in the barracks, they had a building to themselves. So did the officers.

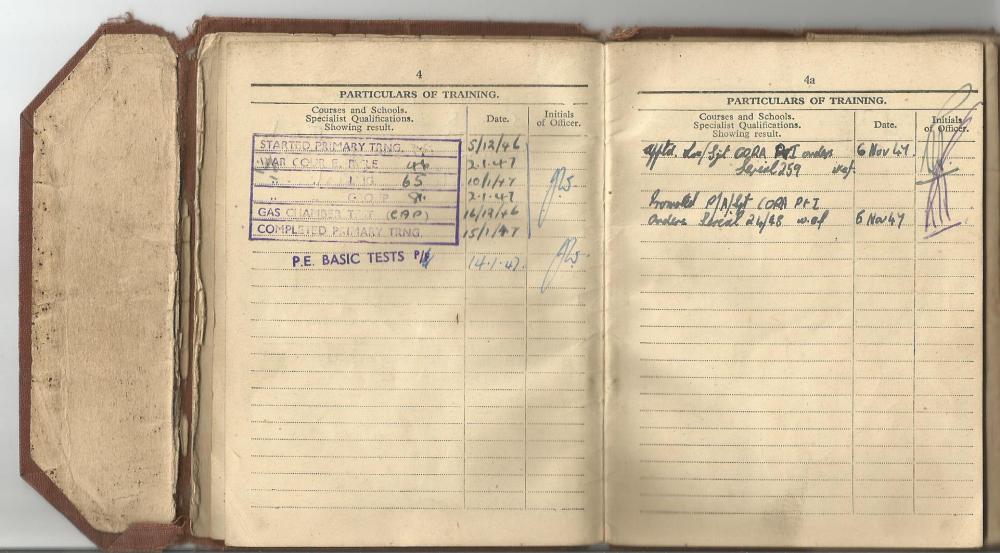

The early weeks were as much indoctrination as training. Ranks, saluting, the regiment, battle honours and all that. Although the barracks were the base of the Berkshires, we were not in the Berkshires, but something called the general service corps. I think we were there about 6 weeks, and we weren't let out for a couple of weeks. When we could march to their satisfaction, they took us out for a route march, across the streets. That felt most odd, seeing civilians and feeling very conspicuous. When later we got leave and could go out on our own but in uniform, I hardly knew how to behave in public. What was the regimental way to do it? The indoctrination was pretty powerful.

The rifles arrived after a few days, and our first job was to clean the damn things. They were in packing cases in solid grease. There weren't such things as Swarfega available. Mine was made in 1917. We had already attacked our boots, which we were instructed to make like patent leather on the toe caps. Spit and polish does it. And the brasses on the webbing, and the blanco on the webbing, Khaki-green, number 3. Those who couldn't iron learned how, as all our clothing had to be ironed in the specific manner for kit inspection. Everything was set out on the bed in precisely the specified layout. This was one of the times we saw the officers.

There was some military training- I don't remember if we actually got to firing the rifles, but we took them to bits, and learned how to load them. Most of it was drill.

It seemed most of the day was taken up with changing clothes, from fatigues, (overalls) which we wore most of the time, to battle dress for drill, to physical training kit, to fatigues to battle dress, with small packs of ammunition pouches, to FSMO (field service marching order - full webbing, big packs on the back, small packs on the top, ammunition pouches, gas masks.) I wasn't very good at physical 'education' and had a couple of goes before I got through the test. If I hadn't I would have gone to a PE unit for toughening up.

There were fatigues too- housekeeping jobs, essentially, sweeping, cleaning, peeling potatoes. I got to clean in the officer's mess. Much nicer there, own rooms, coal fires in the grate.

Posting

From that unit, we were posted to our various regiments, or corps. There was an interview with an officer who recorded what one had done. I was posted to RASC - service corps- to train as a clerk. It was the education, I suppose, and a brother in the corps. Some got the intelligence corps which sounded good. That could have been languages. I expect I could have got the medical corps. One chap was posted to the army fire service. He was a smallish red haired chap, and I remember his baffled fury, jumping up and down saying "I'm a bloody engine fireman. I'm on the railway".

Officer Training

I was posted first to an RASC supply depot near Taunton, at Norton Fitzwarren, but I didn't stay long as I was soon sent to Aldershot to a junior leaders course. The idea was to prepare people for an officer selection board. I didn't go on to that, as I failed the course.

It consisted of infantry training, though it was the service corps. Lots more drill, weapon training, tactical exercises. This time we did get to fire the rifles, and the Bren and Sten guns. We took them to pieces and put them together again. It was all done as a drill. Naming the Parts (of the Bren gun, one of which was the Ladies Delight, the body locking pin). "You'll remember that, won't you?" Apparently so. The Bren guns, (Brno-Enfield) were my favourite, as they were so beautifully made. The Sten guns were tinny and inaccurate, just for short range spraying.

There was a lot of drilling, taken by the Regimental Serjeant Major sometimes. We were in Buller Barracks. We could sometimes hear, from the next barracks, Mons, a high pitched cry. This was Tivvy Britten, a famous R.S.M., taking parade at the officer cadet training unit, where we expected to be going.

Aldershot Barracks in January 1947. The junior leaders course. It is the only photo I have ever seen of Dad with this expression, looking really relaxed, in mid smirk and cheeky. He is standing on the left holding his hat.

It was very cold that winter of 1946-7. As the snow fell, and the roads got icy, marching and drilling became hazardous. "Dig yer 'eels in- if yer fall over I'll tread on yer face" said the serjeant. We dug out heels in and didn't fall over. It still works. It got so snowed and frozen that with the coal strike, things got rather difficult. Much of industry shut down, transport was chaotic, most of the army at Aldershot went home. We didn't. Stayed right through. They gave us extra blankets when the fuel ran out. It wasn't just that the water for washing was cold. We had to break the ice to get any water to shave. I can quite precisely date to this time the change from not feeling the cold, like most young people, to feeling it. I have ever since been miserable to be cold.

I was ill at one point, with flu, and spent some time in an army hospital. The Victoria I think. That was quite a pleasant interlude.[We have some old Penguin classics with 'Aldershot 1947' in them; lots of George Bernard Shaw was read!] I recall the ward sister, a small white haired woman, very efficient, and pleasant to be with. She was interested to chat.

I had taken up smoking a pipe some time before, and I remember snapping the stem of my favourite little black pipe which I had in the battledress pocket on the front of the right thigh. When I was getting ready to leave hospital, I put my foot up to tie my shoe lace and 'snap'. Can see now where it was mended.

The people on the course were interesting. One was, surprisingly to both of us, Maurice from school. He passed. I can remember a chap from Haileybury school, Heron, and another I was quite friendly with, Fellows. He was sexually experienced and we discussed ways and means.

I think it was two minor disasters that finally scuppered my chances- those and a general unmilitary uselessness. We had exercises in the country, small operations, with roles assigned to various of the group. I was in command of one, where there was a scrubby field alongside a road, with a wood ahead. Paratroops in the wood. I not only got us all killed, but lost my temper with some of the others. My tactics were good, they said, some to dodge from bush to bush in the field while others crept up the hedge- but my execution wasn't. Perhaps they had already formed their doubts and this was make or break. A few days later there was another, with Maurice in command. He did all right, until we got caught in a wood when the gas came. I can quote from a letter to Jean, 11 February 1947-

'We had to cross a river and capture a hill. The surrounds of the pond were all wooded. It was normal and satisfactory till we got to (a point on a diagram). By the way, the river was about 2ft wide. At X there were smoke canisters. White smoke is a bit smoky and choky when you're near the canister but there was a canister of yellow smoke. Many of us got lost in it and got caught in the trees. "Run and get the smoke out of your lungs" they said. By the time I got out I was in a terrible state, eyes, nose and mouth streaming, chest burning, stomach blown out. From my eyes to my stomach was one burning fire and I couldn't breath. My God, I was in a state. Fellows were collapsed all over the place. We were egged on to the end, but I was nearly dead. I couldn't be sick, but some lucky fellows were. Two went out, and more were laid on a lorry. One was quite delirious, the other looked ghastly. When we got in the lorries to go to a pub for our haversack rations, I was laid on my back with my head supported. After forcing down some dinner, I felt a little better, but I laid on my back on the floor again. Icsy got it bad too, so did half a dozen others. By dinner time most had recovered except Icsy, me, Eric Vogel and these two corpses. All the hot water's been off everywhere including the officer's mess and the only fires allowed are in the cookhouses. C.S.M. says the Paratroops and the Guards have gone home.'

Anyway, at the end of the course, I was RTU- returned to unit. I was hurt, and felt it unfair, and went to see the commandant to say so. But it made no difference. I could always try again when I was more ready, he said.

Cirencester

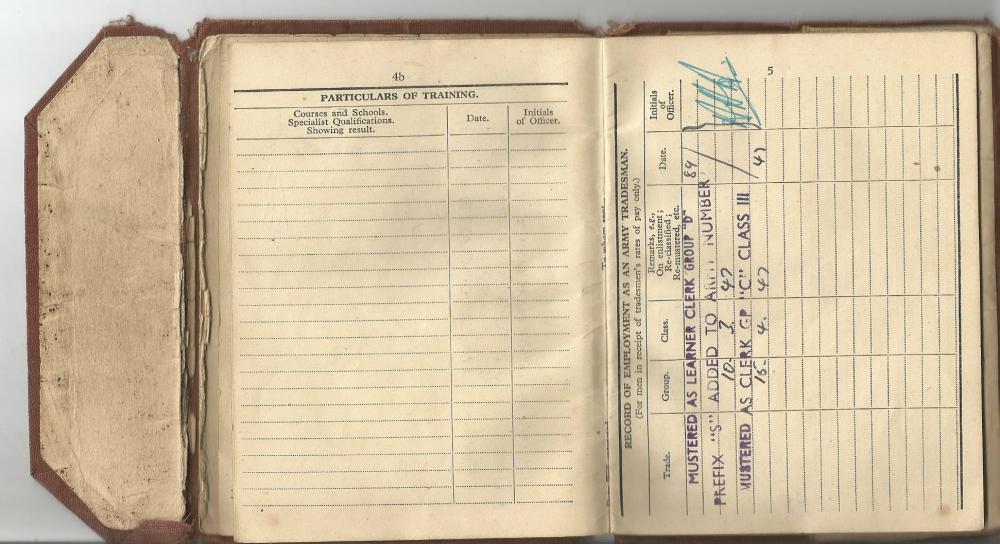

After a few days leave I soon went to a camp outside Cirencester to train as a clerk. On arrival in March 1947, I was 'mustered as a trainee clerk'. It was all more amenable. No drilling, except for finger practice on the typewriter. Mine had the keys in two semi-circles on either side. I passed out at 19.2 words a minute. When I took typing lessons in 1988, I passed out with 25 words a minute. Some improvement for forty years. There were all sorts of useful things on the course, about filing, and types of letters and their layout, and such, which have remained useful. I still habitually write abbreviated dates in the army way, e.g. 20 Jun 89.

Life in general was easier, and it was good to go into town, which I liked. Our corporal was quite friendly. There was a song about at the time, "Open the door Richard, open the door and let me in" which was chanted on suitable occasions. The camp wasn't a barracks, but consisted of Nissen huts, with sort of bitumen floors. The only bit of bull was keeping those floors polished. They came up a beautiful shiny black.

There were ATS on the camp, and we had dances, and a sort of informal contact. One of the pretty ones who sang had a certain reputation. It was an attractive prospect, but not tried, in spite of a sort of generalized invitation to two or three of us who escorted her to her hut after the show.

I went home for some weekend leaves too and the journey became familiar. Paddington to Kemble junction, then wait on the little, very rural-seeming station for the branch line puffer to Cirencester. I don't know how we got from the station to the camp. There may have been buses, or maybe lifts, or even army transport.

When I passed out in April, and was recorded in my pay book as 'mustered Clerk Grade 3,' I was posted to a supply depot at Exeter. There were more favoured postings. One notice posted up was for someone at the British Embassy in Helsinki. It wasn't me.

I don't remember much of the work or camp at Exeter, in Topsham Barracks, but I do remember the walks on the river bank, and the pubs where we bought rough cider. That was a revelation. We didn't call it scrumpy though. The weekend journeys to Exeter were still from Paddington by Great Western. Not to the main station St David's though, as that was Southern Railways, from Waterloo.

I became friendly with one of the only two army acquaintances that I met again after the army. He later sent me a photo from Japan, which I still have. His name was Tony.

I looked at some old letters, and found things I had quite forgotten.[Letters which sadly for me, he must have destroyed, so that my mother would not come across letters relating to his life with Jean, after his death]. There was talk of possible promotion in this little unit, which was a small supply depot at the top of the Topsham Barracks site. These barracks were apparently the Devonshire Regiment's preliminary training unit, and we saw the new recruits arriving. "Bewildered and miserable looking civilians". We of course, were soldiers.

It was a matter of weeks until the posting came, to a holding depot in Thetford, of which I remember nothing. Tony and I both went. It is clear from letters that not until a day or so before sailing did we know where we were going. I was making inferences from the length of embarkation leave, which was supposed to be longer if postings were to the middle and far east, but it didn't seem to work like that. I had about 18 days embarkation leave, during which Jean and I got engaged. At Liverpool Street Station, to which my brother took me in his van, I met up with Tony and his girl Chic. After the army, he, Chic, Jean and I went on a skip up the Thames from somewhere like Windsor. She was a dainty little thing, Chic and worked at painting numbers on watch faces. With luminous radio-active paint. Can you believe it? None of us thought anything of it.

Geoff and Jean, engaged at eighteen; the picture he had on his desk in Germany.

British Army of the Rhine Bielefeld

'It was a bit of an adventure, as I had not been overseas, though I was not keen on separation from Jean by then. The journey was through Harwich, by passenger boat to Hook of Holland. The journey was repeated on leaves. No state rooms, white painted metal, lots of pipes and smelling of oil. But in the morning there was Holland. We were put straight on a train, across Holland to the German border at Venlo. It felt like being packaged, rather than travel.

The destination was Bielefeld in Westphalen. Bielefeld was a medium sized town, not damaged, but which had the convenience of a large barracks. It was a holding unit. I got into swimming there and won something at a gala, probably for the plunge.

The nearest I ever got to being on a charge, was here. At least I think it was. It was when I hopped back through the hedge from the house of the lady who did the washing next door. I didn't look first, and a Regimental Police corporal nabbed me with glee and marched me before the Camp Commandant, who said something to the effect that wasn't I in the swimming gala and that I should be more careful next time.

Hilden

When it came my posting was to the headquarters of the Second Infantry Division in a barracks at Hilden, a few miles outside Dusselforf. I was there for some time, and began to go out into the city. A couple of us tried to buy a beer in a bar. We managed the language. The essential phrase one learned was 'Was kostet?' The beer was awful, watery, tasteless and fizzy. It came out of a stainless steel tap. Just like now.

The other phrase one learned was 'jig-a-jig?', which might be expected from prostitutes, and could be tried with 'bints'. I didn't realize that it was Arabic for sister. In fact I was accosted more than once, but didn't indulge. At camp in Bielefeld, the essential acculturation emphasized the availability of P.A.C.'s, prophylactic action centres, which we were strongly advised to visit after any sexual encounter. The airlines in Bangkok do the same now.

I worked in the office of the Director of Supplies and Transport, who was a sort of staff officer, a colonel, who fixed things up which were effected by the Commander (C.R.A.S.C.) who seemed to be in actual charge of the various units and depots. I don't think I was too clear about it then and I'm certainly not now. I know there was a rifle competition coming up, and I was supposed to arrange for the entries of the R.A.S.C. units. Something got ommitted, I think. One day I had a phone call from someone who was a bit annoyed about not hearing about something or other. He was getting a bit shirty, and I was objecting in some way. "Anyway" he said " do you know who you are speaking to?" "No". "I'm C.R.A.S.C" "Do you know who you are speaking to?" "No". So I rang off saying "Thank God for that."

We occasionally had contact with the government, which was AMGOT, Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories. Before I left Germany there were elections, and posters were to be seen 'Wahlt KPD' 'Wahlt FDP' but at this stage it was still very much occupied.

We used to take turns on night duty. On one occasion the colonel gave me a contract to type up. It was in French, and of course full of accents. There may have been a typewriter which did it, but I made so many mistakes I knew I would never get it good enough, and phoned the bloke up at home to say so. He didn't insist, I was glad to hear.

There were about three soldiers and a couple of German civilians in the office. One girl was, I think, called Elsa, and the other Hildegard? She was blond and slightly plump, almost the archetypal fraulein, though very pretty. I got on with both of them quite well. Hildegard was a little worried one day, as her father was attending his de-nazification hearing. "Why?" "He was a colonel in the Waffen SS". He got through. "He was only Waffen SS, not a Nazi, you know". Funny thing, there weren't any Nazi's anywhere.

I managed to develop a painful thumb and reported sick- went to see a doctor. He said that it was a whitlow and he had better lance it straight away; so he froze it and lanced it. It healed well, but I can still see where the little scar was.

Polio

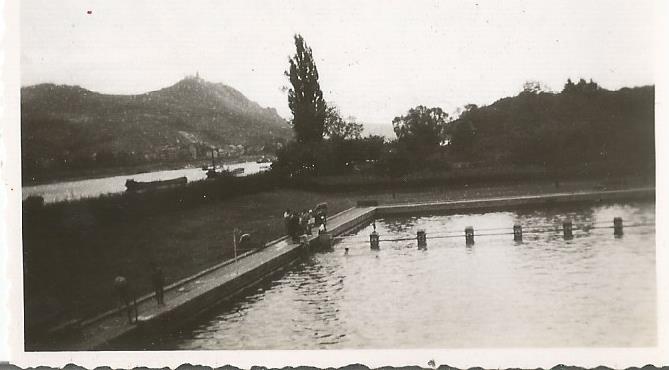

From the camp, I went swimming in the Rhine at a bathing station near Bad Gotesberg. It was most likely there that I caught polio. There was an epidemic in that year, 1947, thought to be contracted from swimming in the Rhine.

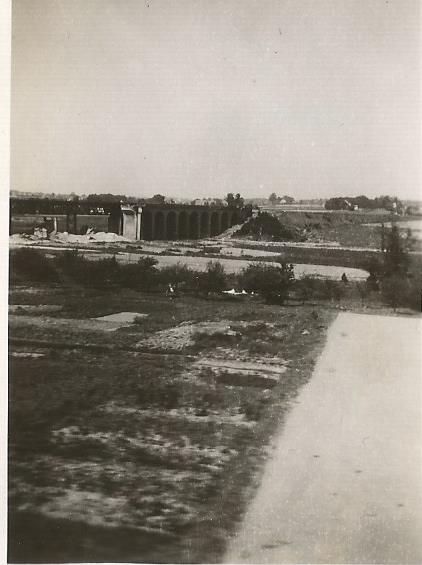

Bathing station at Bad Gotesburg, Sunday 21st September 1947, after recovery from polio. The back of this set of photo's says 94 Club day trip to Bad Godesburg from Dusseldorf. The 94 Club was the NAAFI base at Dusseldorf.

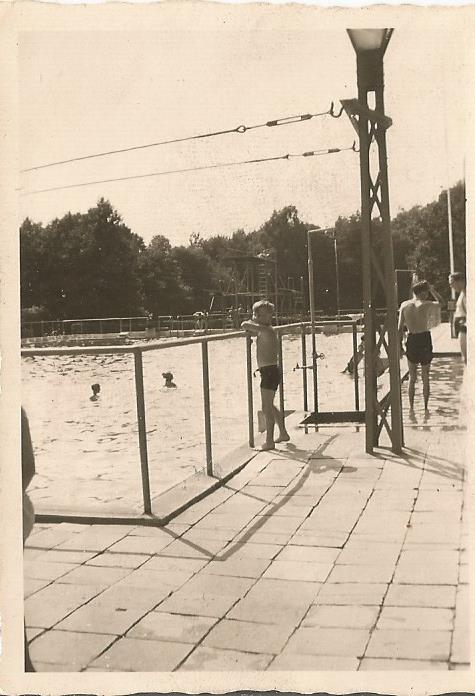

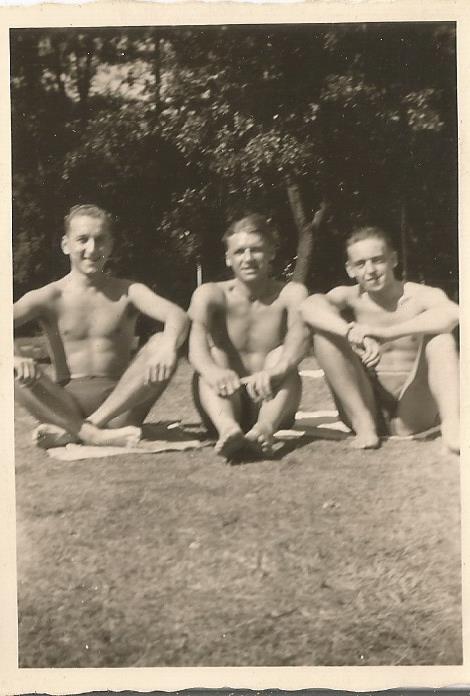

Swimming at Hilden with civilian Germans, after recovery and return to the unit, August 1947.

The same day

Polio began with what I thought was probably flu, and I was sent to the casualty clearing station in Dusseldorf. It was one of the great 19th Century merchant houses along the river front. I remember the view out of the window, but I wasn't recovering, as it happened. I was soon on my way in an ambulance which I remember in a dazed sort of way. It took me to hospital in Wuppertal, as I later learned.

I came to in a hospital room by myself. When someone came in I asked where I was and learned I had been delirious on arrival, and then in a coma for ten days with a very high temperature of 110 or something. I said you die if your temperature is 108, and the nurse said "we were a little worried about you"....they soon put someone else in with me and we talked a lot. I wrote my autobiography. If I had kept it, it would have saved me from some memory lapses now.

When it came to convalescence, I was sent to a centre at Travemunde on the Baltic Coast. There was one amusing encounter with a porter on Hamm station when I was on my way to Travemunde. I asked in halting German which platform for Hamburg and he replied, in an excellent Welsh accent 'Well, it goes from platform 7, look you'. He had been a prisoner of war near Cardiff. By 1947 they were coming back.

Incredibly, Geoff was not paralysed by polio.

There was one incident at Travemunde, when four or five of us had gone out for a drive in a 15cwt truck. We got a bit lost, and going down a forest road we wondered what the barrier ahead was, with soldiers who didn't seem to be wearing the same uniforms? We stopped and turned round smartly, as we didn't actually want to be arrested by the Russians, or shot at. It was already getting a bit cautious, though the Cold War was not yet in full stride yet.

When I went back to the Div HQ, I was supposed to be fit. There was an education centre there, and I went to find out what was going on. I struck up an acquaintance with an education serjeant, who seemed by his own admission to be on to a good number. So I applied for a transfer. It wasn't long before it came through, November 1947, and I joined the RAEC.

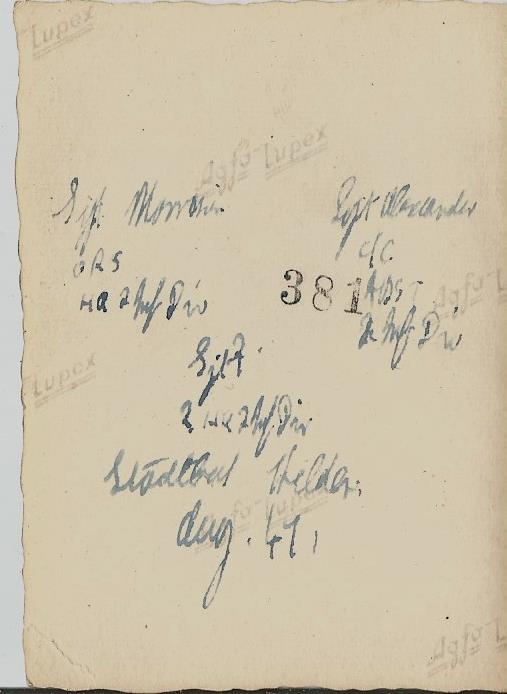

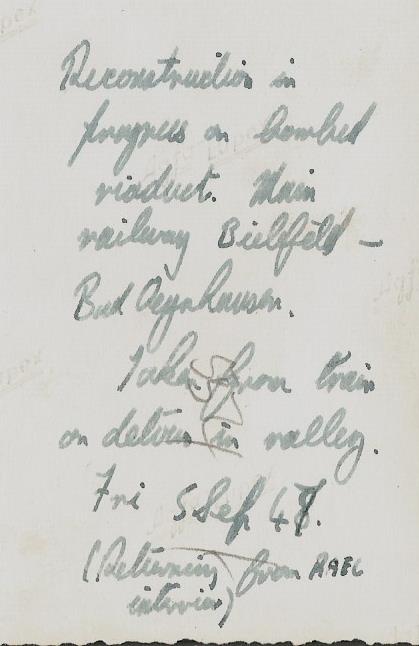

From this, we see that he went by train for an interview for the Royal Army Education Corps on the 5th of September, 1947. He must have got these films developed in 1948, as he wrote 8 first, then overwrote it with 7.

Royal Army Education Corps Training at Gottingen

The training for education took three months, at the College of the Rhine Army, Gottingen. Gottingen is an old German university town in Westphalen. It was a beautiful town, full of character, though like all German towns at the time, shabby and very much down at heel. The 'college' was simply a large army barracks some way out of town.

What with one thing and another I was beginning to see quite a few German towns, if only from the railway. The devastation in the Ruhr and in Hamburg was not like anything I had seen. Hamm, Essen, Wuppertal, Hamburg, Solingen, were all names I knew from news in the war of air raids. The centre of Hamm was all shells of buildings. The centre of Essen was mounds not of rubble but of earth. Hamburg seemed to be large flat areas of roads cut through a sea of rubble. Not all of any of the towns were as bad as near the railway, but the damage was immense.

At the camp, as soon as I and the rest of the batch arrived, we were made up to serjeant, acting unpaid. As everybody to do with the course was at least a serjeant, it made no difference, though there were other units around with privates. It certainly made no difference to the Regimental Police.

By and large there was little contact with the German population. Fraternization was forbidden, and the army stayed pretty self contained, like modern tourists on a package holiday. Gottingen was a strong Nazi place, and I was told the Horst Wessel song could be heard from houses or bars at night, but I never heard it.

There was an occasion I remember well in feeling, but not accurately enough to locate properly. I think it was in Gottingen. For some reason, I went out on night patrol with the provost serjeant. That took us round the night spots in town, routing out the squaddies who weren't supposed to be there after hours. It was about the first time I sensed real resentment in a crowd. We were, after all, an occupying army in a defeated country. We weren't popular with the squaddies either. In the morning we had to march them up on a charge.

The teacher training was good. It was all done by officers, who were clearly teachers by profession. We learned about different teaching methods, lectures, discussions, lecture-discussion, lessons and so on. We had to practice them on each other.

My lecture was a bit of a good one. We had to choose and prepare our own topic, and I took up the business of languages, and peoples, and did a piece on the peoples of Europe. There must have been some reference books, because I'm sure I got some new information on Huns and Slavs and Celts and all. I must have got quite excited, as I broke the blackboard pointer. I got a very high rating, and the officer was most complimentary, holding it to be an example to be emulated. This pleased me, as so far, nothing had gone really well in the army, and I had clocked up some hurtful failures.

I guess he used this!

There were church parades every Sunday. Except for a padre saying prayers in the Aldershot hospital, this was the first compulsory prospect I recall. All of the C of E and non-conformists had to go, but not the Catholics, the Jews and me. So one chap who was a Catholic, a Jew called Greenspan and I had little discussions while the others were praying. They were fun- on why have confession, Jewish jokes and so on. Greenspan was a butcher. I noticed later a butcher named Greenspan in the Finchley Road, but I didn't go in and ask.

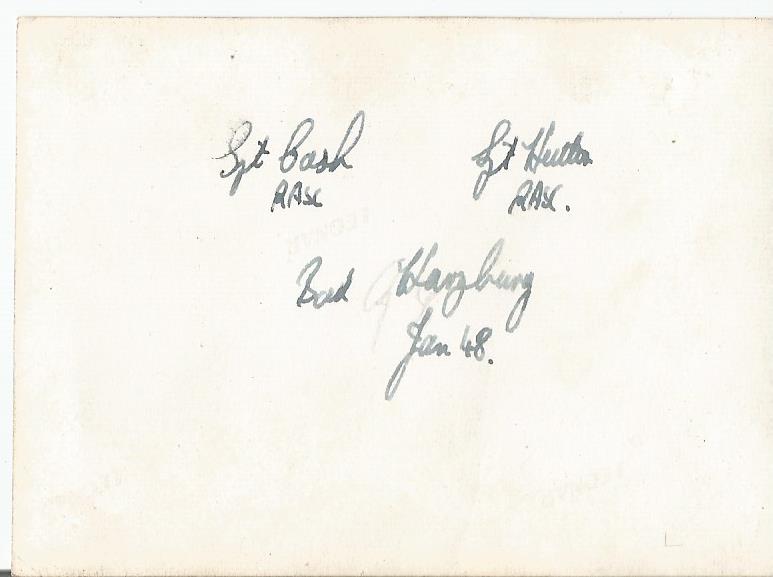

We went on a short holiday trip to Bad Harzberg in the Harz mountains for the winter sports. But the snow had melted. Bad Harzberg was a different Germany again. Solid stone, steep roofed, nineteenth century hotels. Slight air of faded gentility, like Buxton in the fifties.

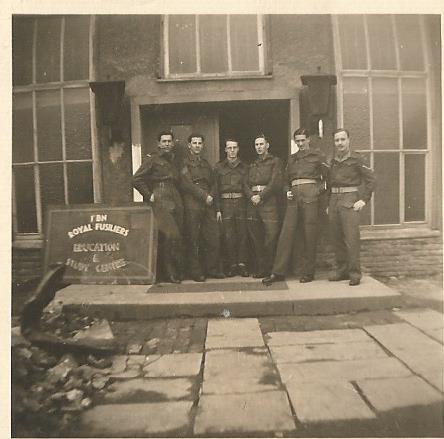

One of our treats was to be taken to a Rhine Army or Divisional tattoo somewhere. It had most of the usual stuff, bands, marching and so on. One event was remarkable. It was drill without commands, by a company dressed in eighteenth century uniform, and pretending to be toy soldiers. I had never seen anything as precise. 'A' Company, 1st Battalion Royal Fusiliers. They had the Guards knocked into a cocked hat, or Shako.

When our postings came through, I was posted to the 1st Battalion, Royal Fusiliers. I learned later from 'A' Company that there was someone with a torch hidden under the grand stand.

1st Battalion Royal Fusiliers at Iserlohn

According to the website 'British Army at Iserlohn 1945-1994', a new unit the 5th Infantry Brigade had been formed and the HQ moved to Aldershot Barracks Iserlohn on the 1st of September, 1947.

This badge was in Geoffrey's old badge box and I had no idea what it symbolised. It's the 5th Infantry Brigade, which was formed out of several regiments it seems.

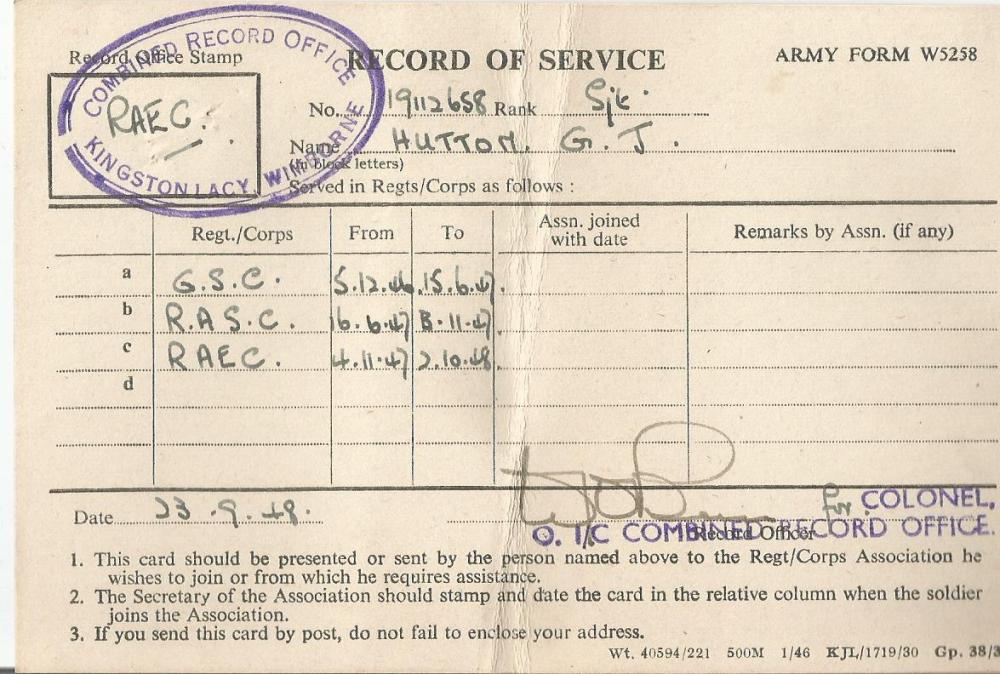

According to his diary, he had a passing out parade on 28th January 1948. He was posted to HQ28in att. 1st Btn R.F. Iserlohn on 29th January. He arrived at 'HQ 5 Bde' on the 30th, and arrived I.R.F. on the 31st. His job was to

'teach the less well educated squadies basic Science and Maths.'

He was only 19 himself.

He went home to London on leave on the 11th of February, arriving on the 12th and went to a dance on the Saturday, which was St Valentine's day. He went to a concert at the Royal Albert Hall on Wednseday the 18th, Rachmaninov, Delius and Sibelius. I can't read all of the entries, but on the 27th it says Mr Wood UCL, so was applying to university. He went back to Germany on the 3rd of March, so quite a long holiday.

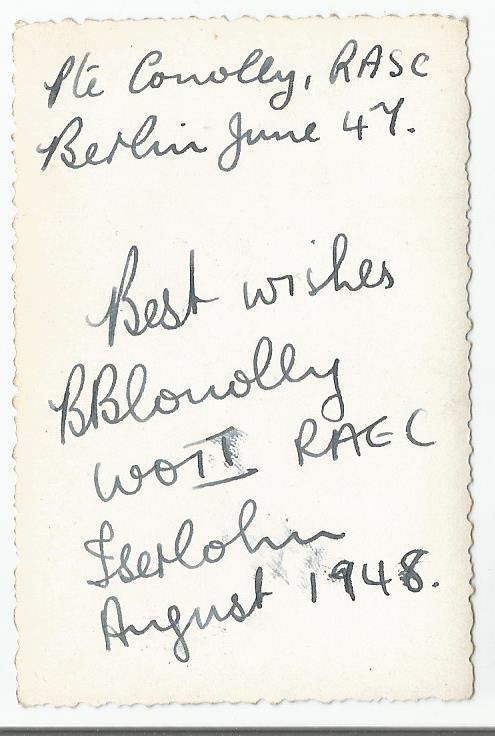

Here they are at Aldershot Barracks, Iserlohn, April 1948. Left to right, they are L Cpl P Horn, Sgt D P Honey, Sgt B B Conolly, Sgt G J Hutton, L Cpl Chandler, L Cpl Keene.

I spent the last eight months in the army with the 1st Battalion Royal Fusiliers, and it was a better time then anything before. They were a nice lot, and I made good friends, though not surviving discharge. I did, though, send them a telegram on Albuhera day the following year.

The regiment was stationed at ex-German army barracks just outside Iserlohn in the Ruhr. When I arrived, I reported to the office and a C.S.M. took details. He was the only person who ever commented on my religious denomination. He said that wouldn't do me any good, and I said it wasn't supposed to, and nothing more was ever said. He also made me take off the little coloured felt disc we wore behind our cap badges on the course. He said we didn't do that here. I got on fine with him from then on, both he and his wife. They lived in married quarters, and took quite an interest in me, and what I was going to do. When he was the quiz master for a quiz in the mess, he was egging me on when I missed one question which was the name of a BBC political correspondent- surely I knew that!

I didn't belong to the Fusiliers. I was attached, like the medical corps, and the REME. Nevertheless, I was made very welcome in the Mess, and was treated as a member. I missed out on some regimental duties, like parades, and exercises, and manoeuvres on Luneburg Heath. I wasn't involved in one very secret duty some were assigned to, which turned out to be the guarding and transport of the new currency when Germany had a currency reform. Overnight, the Reichmark was replaced by a new Deutshmark, a thousand times or so its value. Adenauer's new Bundesrepublik was getting into its stride.

There was a lot of feeling for the regiment, even if joked about and dismissed, and I picked some of this up. I no longer felt the army as a hostile and alien agent doing things to me. I belonged, if on rather odd terms. I had come to terms with it, and no longer saw so much indoctrination. The indoctrination was working.

I shared a room, for a while at least, with the band serjenat, Robinson. He told me a lot of the history and background. He was a regular, as were a good many of the serjeants and WO's. He joined as a bandsman, before the war and went to Kneller Hall, the military music academy.

The Royal Fusiliers, City of London Regiment, 7th of Foot. The only regiment allowed to march through the City of London with fixed bayonets, flags flying and bands playing. Full dress for the band, a bearskin, with a white flash up the side. The regimental march, was, I think, a music hall song from the Boer war or earlier. 110 beats per minute, which is slow. The regiment had battle honours from half the places in the Napoleonic wars, and since, if not before. Minden Day was celebrated. The big day was Albuhera Day, when there were parades and junketings. Their blanco was different too, khaki-yellow.

Although I never really became a soldier, I got used to being a serjeant, even to the point of saying 'thank you, corporal' to the Regimental Police at the gate who spotted a button undone.

Serjeants' Mess, Iserlohn

When I first went to the Serjeants' Mess, the R.S.M came in and welcomed me and offered a pint. I thanked him and said "no thank you". I shouldn't have done that. Others pointed it out that I should have accepted and returned the compliment later. I did make amends. There weren't any problems with him. Only once there was a slight crossed line. It was much later on, but one day there was some silly business with some others, and one fellow serjeant pushed my armchair over backwards. Just as I was lying on my back on an overturned armchair, the R.S.M. walked in. "Not the proper position for the Mess, is it Serjeant?"

There was a lot of rather adolescent fun in the Mess. The Fusiliers were in the Second Infantry Division, in a Fusilier Brigade with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and Royal Scots Fusiliers. They visited sometimes, as did other local regiments. One of the fascinating ones was a cavalry, not infantry, the 10th Hussars, from Hameln. Their serjeants wern't. They were Corporals of Horse. Not that they had horses, of course.

We played housy-housy on Saturdays, otherwise known as Tombola. Nowadays it's bingo. Two little ducks, 22. Top of the house, 99 and so on, some not so innocent. On these Saturday nights, the wives came in, as many of the WO's and Joes (Warrent Officers and Serjeants) lived in married quarters. That didn't stop the sermon. Neither did the presence of the Padre on those nights when we entertained the officers. One of the serjeants, whose name I forget, but whom I can visualize clearly, dressed up in a sheet.

"The Salvation Army will march past in fours. Sister Ada will lead the parade. Sister Tucker, the other fucker

Sister Hannah will carry the banner"

"But I'm in the family way" "You're in everybody's way" and so on

"The Lord said unto Moses 'Come forth' but he came fifth and lost his beer money"... and so on.

"To the woods"

"I'll tell the vicar"

" I am the vicar" and so on.

The point about these recitals, which were much longer than I can remember, is that we all knew them by heart, and the ritual was still funny, though the level of humour is reminiscent of the fourth form.

Japanese Cruelty in Burma witnessed by members of the Mess

There was, of course, a more serious side. Many of the members had fought in Burma, along the Irrawaddi, alongside the Indian Division. The stories of the Jap behaviour were appalling. They captured one Indian Subadhar (R.S.M.) and crucified him within sight of his troops. He ordered them to shoot him. The Japs also killed prisoners, by bending down two saplings and tying the prisoner to them, so that he was torn apart when the trees were released. These were the clever, gentle beauty-loving people whom we were supposed to emulate.

Some of the members, including the preacher, had been later in Calcutta when there were riots, and had been ordered to fire on the crowds. He said it was the worst thing he ever experienced. No-one was triumphant or gung-ho, but scarred and saddened by their experiences.

Teaching

The work in the Education Centre was quite amenable. There were four or five of us. Con was a Warrant Officer, WO2. His name was Conelly, from Cockermouth in Cumberland. He had been a cub reporter on the Cockermough local paper. There was another serjeant, Colin Honey, and a corporal Horn, as far as I remember. Con and I were very friendly, and I regret not seeking him out after demob. He sent me a Christmas card after I was demobbed, with a picture of Gottingen. I still have it. Horn was the other one I ran into afterwards. By chance in a coffee shop in London. He updated me on news. One of the corporals I knew had shot himself, which was surprising and a bit shocking as I never would have thought it of him. I've forgotten now who it was.

Con

I taught general science, maths (maths?) and BWP- British Way and Purpose, which might have been traditional, constitutional, conservative and imperial. It wasn't. It was said of the R.A.E.C. that its only battle honour was the 1945 election. It said on my effusively complimentary demob testimonial that I was in charge of equipment and syllabuses, but I don't remember that.

The classes were for soldiers and some youngsters we had, boy soldiers. They must have been in the band, I think. The only person I ever put on a charge was one of them. Once some horseplay stopped when I said if it didn't I'd put the next to play up on a charge. Except for one who couldn't resist. He was shocked when I did. I charged him with disobeying an order. Section 19, but Company Commander, a Captain, said he thought I ought not to use that as it was really for mutiny. How about Section 42. That was the usual catch-all, conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline. He got three days CB- confined to barracks, with extra parades and things. It wasn't long since I was playing up the teachers at school.

I got to go on a course too. Once to a training centre in the country, at Ludenschied, to learn about basic education (illiteracy). That was interesting, and we got to see something of the countryside, too.

Some of the group of postcards he bought of the area, taken pre-war-

Once a group of us went to the Mohne See, the lake above the Mohne dam. Three of us went out in a little aluminium boat, which was fine until a sudden thunderstorm blew up, with a strong wind. The water got very choppy, we got very wet, and found that we couldn't make headway back to the shore. We were drifting quite fast towards the dam. We became a little apprehensive. It seemed like a big rough sea and our little boat seemed like an insignificant toy. We were rescued by a big fast launch like a torpedo boat which came out from the opposite bank. That was fine, except that we were the wrong side of the lake to get our transport back. We cadged a lift round and the boat people, who were German's, said they would see that the boat hirer got his boat back.

It wasn't only the courses I went on. One time, during 1948, a whole lot of NCO's from the Division were assembled in a cinema for some important event. It turned out to be a lecture on the Soviet threat. There was a map of the world with Moscow at the centre, which showed how the Soviet Union was the centre from which the Soviets planned to expand, and could reach all major Western centres easily. Thus we had to be surrounded with a protective ring of steel. We were part of that ring. In Germany, not occupying it.

I was furious. As far as I was concerned, the Russians and we had just defeated the Germans and that is why we were there. And I didn't believe the Soviets were planning military expansion. Surrounding them with steel was hostile, not defensive. Nothing since has made me think otherwise. Of course I was out of date. The game was now cold war, though there was no Berlin wall yet. The Germans were suddenly allies. AMGOT had given way to CCG, the Control Commission for Germany.

Service Club, Iserlohn town, and socialising.

Iserlohn was an ordinary sort of town, light industry rather than medieval university like Gottingen. In the town was a very good services club. I think it was only for WO's and serjeants. They had a good resturant, and I can remember one occasion when Con and I had dined and wined very nicely on devilled kidneys amongst other dishes. When we got up to go I had a distinct impression of my feet lifting about a yard off the ground and of not quite going in the intended direction. It was the first time, I think, I ever felt that. I hadn't thought we'd drunk that much, but we got back all right without being apprehended, which would have been distinctly embarrassing.

There was a piano and string quartet which played there, and Con and I got to making requests. Once we asked for the overture to Coriolan, and they played it, I think the next day. After that, one asked me home. It must still have been forbidden, but it was the first time I had been to a house other than the washer lady's. We went in a tram, and I felt very conspicuous amongst the homegoing crowd. People were none too well dressed. The violinist, for such was he, was living in a flat, as most people do in German towns, although I was only just seeing that. He and his wife made me very welcome and we chatted. This was the paradox, the other side of the movement from occupation of enemy territory to more normal relations. The sense of conspicuousness, was not only the occupation thing. It was also rather like the feeling when I first went out in uniform in Reading.

It wasn't always like that though. I remember going twice at least to the opera. Once I saw the 'Bartered Bride'. It was, of course, in German. The performance was good, and exuberant. The tumblers did proper tumbling, and I noticed, rather to my surprise, how thin they looked. It still wasn't that long after the war and the German economic miracle was years away. In the kitchen of the Mess, I was chatting to the German waiter, when he tipped out the coffee pots and put the grounds in a bag. When I asked him about it, he explained that coffee was very expensive. "Does it taste alright?" "Ach ja! Better than ersatz". I can't remember where I saw the opera. It might have been Essen, if the theatre was still there.

The other opera was Strauss 'Daphne'. I have the programme for it; so I know it was in July 1948, at the Stadttheater in Bielefeld. I was bowled over by it. It had its first performance only nine years before, so it was quite modern. I was just another member of the audience, amongst people who were lovers of opera. It was a German bourgois event. Who knows what these well dressed, but shabby burghers were doing two or three years before? I did notice that when we were filing out, and there were two sets of doors, everyone was using one, so I tried the other, and as it was open I went out that way. Many years later, an Austrian friend, Ber Pesendorfer, making fun of the Germans, said they would file through the side door, whereas Austrians would go straight through the main door. Yes the Germans are publicly compliant, but the charming Austrians were more anti-Semitic and Nazi. They have a strong authoritarian underlay to their charm.

My German was by then getting better by then. I had regular lessons with a tutor who came up to the barracks. I thought I couldn't remember his name, and I have no note, although I do have my German work book. I think now (Feb 1993) that his name was Pohl. He was from Silesia, now in Poland, which is perhaps why I was later told my German was with a Silesian accent. It's quite gone now.

This gentleman had been a prisoner of war, and had formed a very favourable impression of the British, which is presumably why he was collaborating. This was something the French and others took a dim view about in their people. Still, the German defeat was final, and there was no exiled government, or overseas forces. Which is not to say there were no Nazis. Apart from underground SS, there was the US rocket programme and lots of South American hideaways.

He told me that when he was captured, which must have been quite early, he and the others were put into a train at Dover, in the soft seats, whereas he might have expected a goods truck or at best hard seats. He was a little disappointed when I said all British trains had soft seats. He asked me when I got back to Britain to see if I could find him a copy of Thorndike's English Dictionary of Historical Principles. I couldn't, but I never did write to say so.

Shopping

There were some shops in town from which I wanted to make purchases. This got caught up in the change from immediate post-war occupation to more formal arrangements. Our pay was in funny money, baffs, (British Armed Forces Vouchers) which were of course not legal tender in the town. You could change for marks, I think, at least later on, but there wasn't any point. The currency was cigarettes, and as we got rations which I didn't smoke, all I had to do was sell them.

I wanted a stop-watch in one clockmakers, in which the gentlemen were black suited. Obviously a high class establishment, although they were selling a second hand Stopuhr. I asked for it, and assured them I wanted it even though it was for arbeits-something (work study). When it came to paying, I asked if they took cigarettes. They were quite embarrassed, and so was I, but eventually, "Ja oder nein?" they reluctantly agreed.

When it came to buying some very nice wine glasses [which we still have in 2016] I saw in a shop on the hill leading up to the barracks, I got marks first. I bought some silver spoons and sugar tongs too, [which we also still have in 2016] but I don't know if it was the same shop.

Leave

I saved money quite fast, as there was little to spend it on and I was getting 10/6 a day by then, (28/- a week as a private). Each week there was a pay parade, and you asked for what you wanted. Any surplus accumulated as credit, without interest of course. I can remember the pay officer's surprise when I was going on leave and asked for £75. "Have you got the credit?" he said but the pay clerk said "oh yes, plenty". "Going on leave, then?"

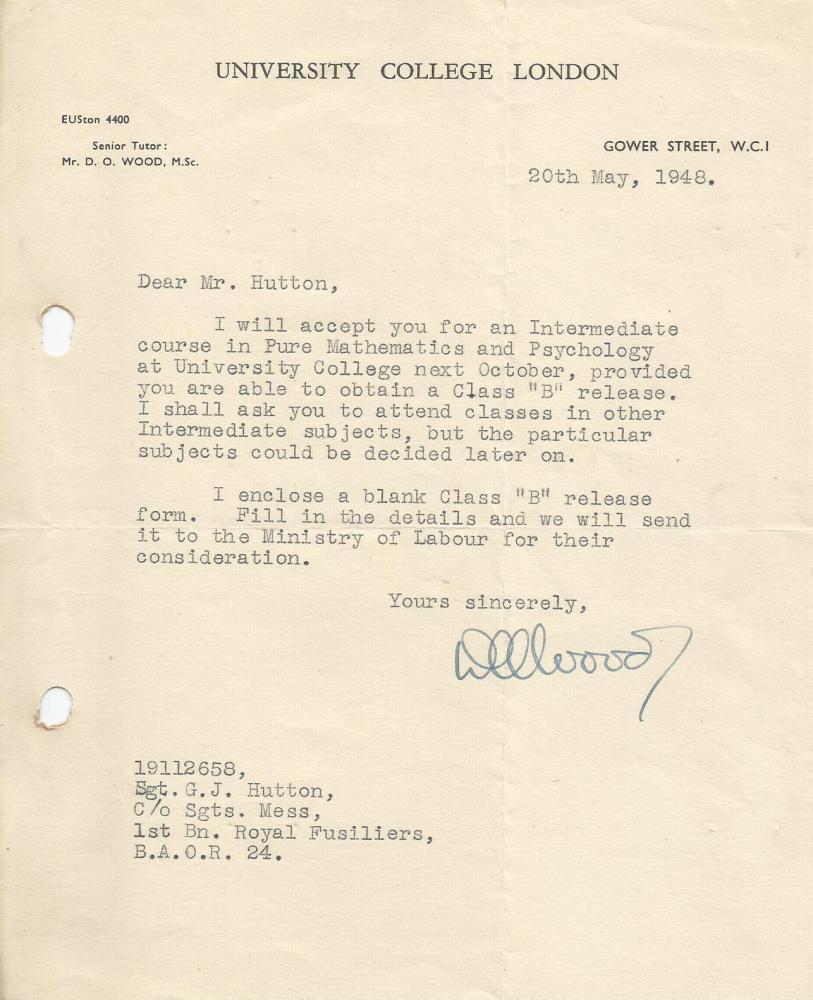

Whilst on leave in the February, he had gone to the interview for University College London and he got the reply in May.

According to his diary, on the 11th of April 1948, he put in his second Leave application. On 15th April, he went on an Admin and Accounting course at some long place beginning with G, that lasted until the 18th.

On Friday 4th June, he left Iserlohn, for Bielefeld and on Friday 11th June he left Bielefeld, going home on leave on Sunday 13th June, going back to Iserlohn by 5th of July, when he must have seen 'Daphne'.

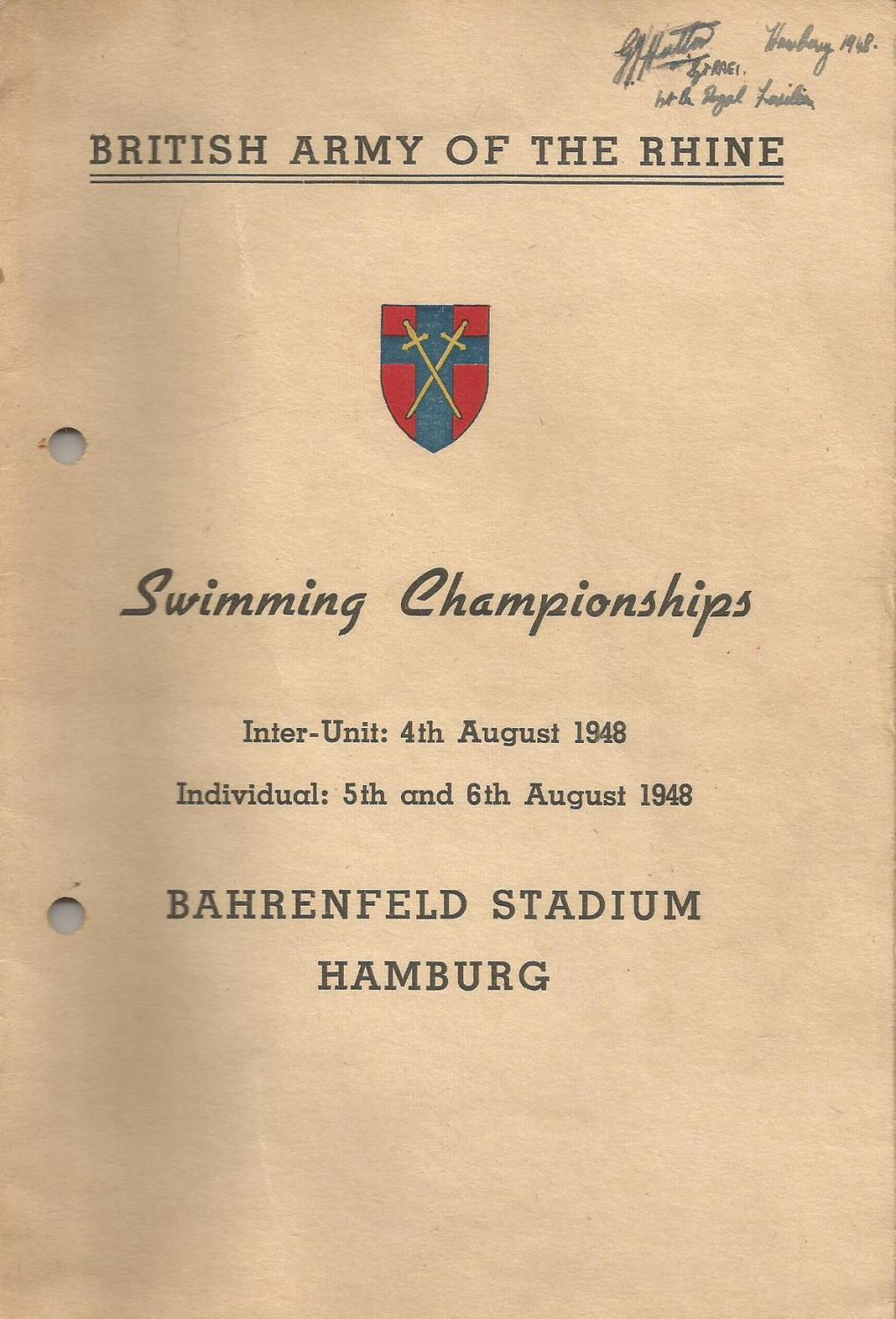

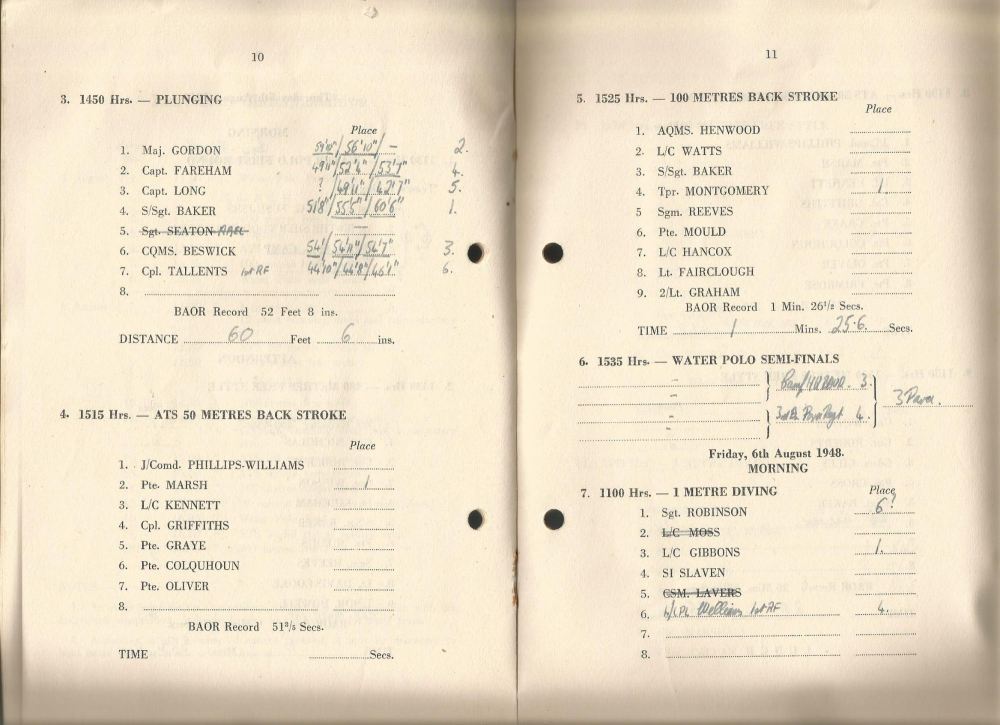

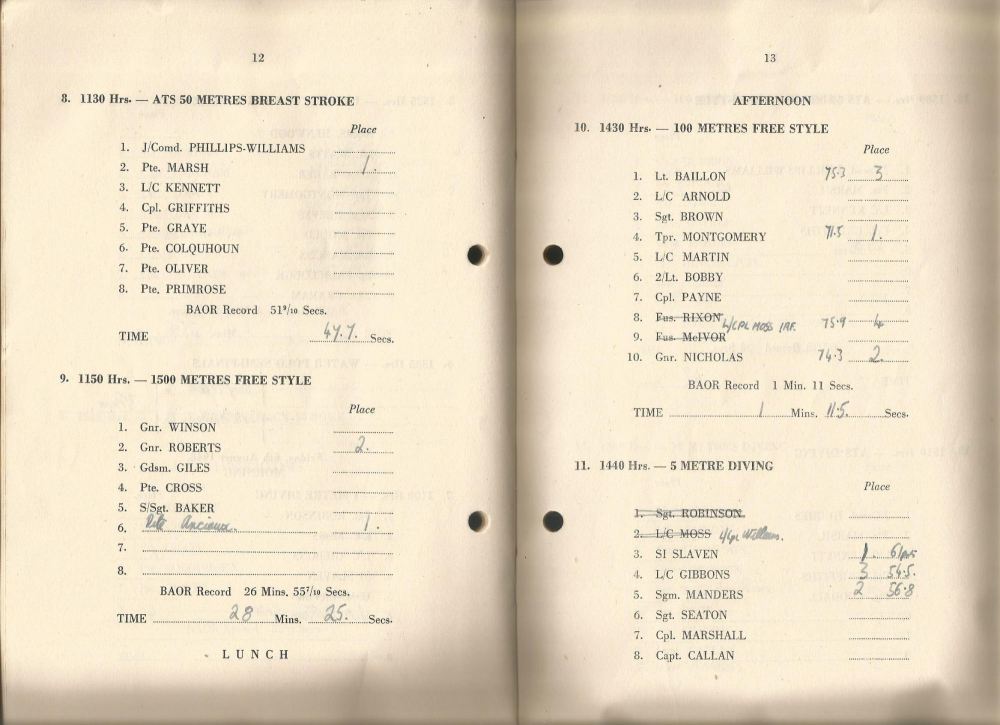

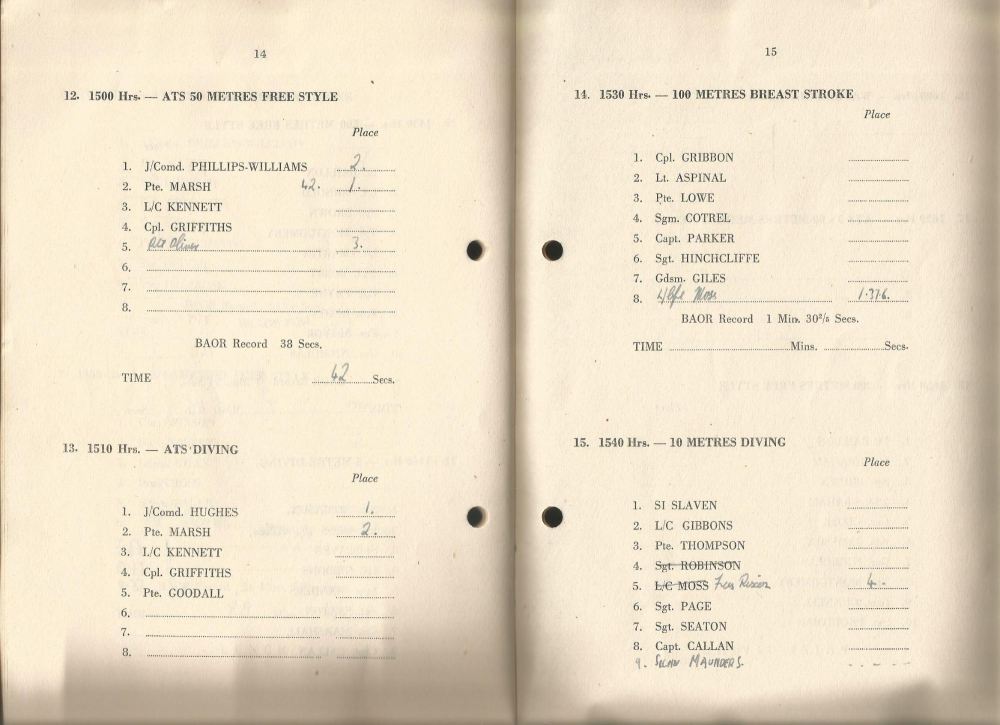

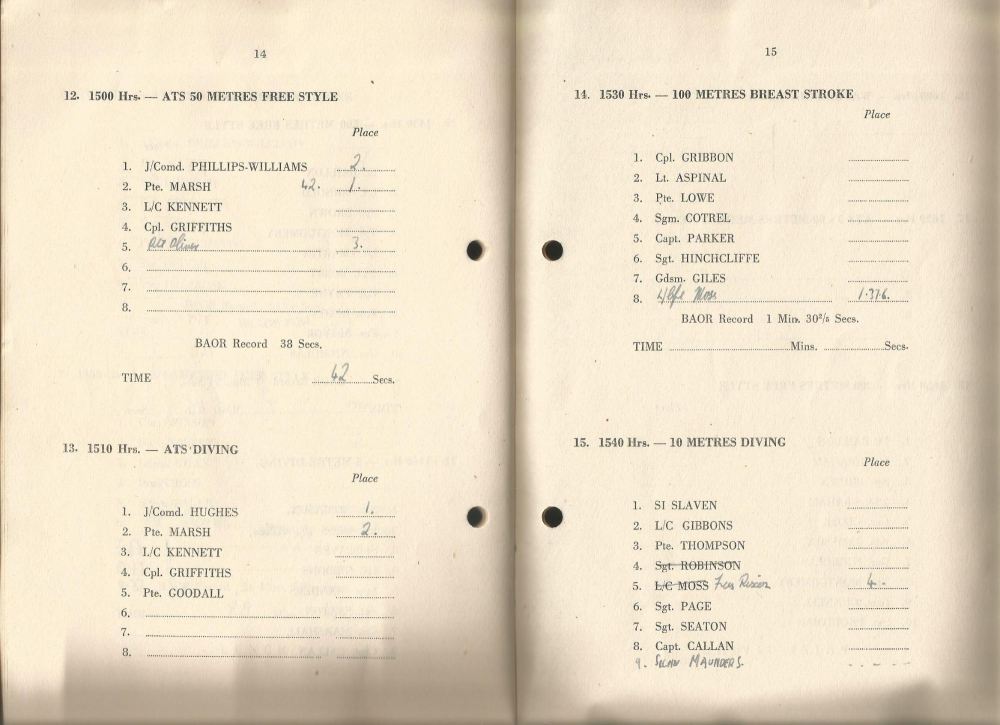

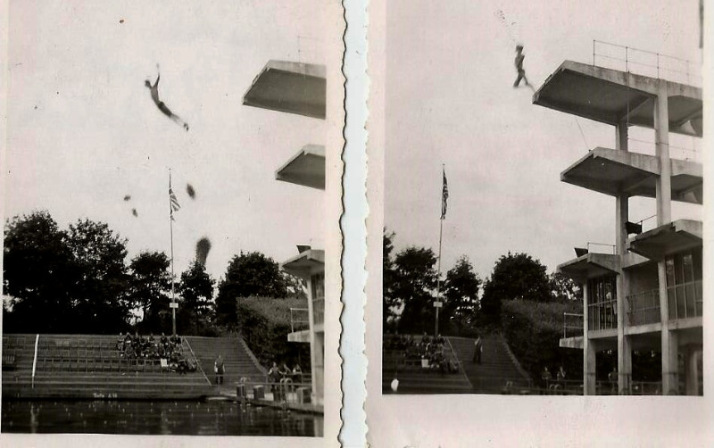

On 22nd July, his Immediate Class B Release came through, giving him special dispensation to go to University before the end of his National Service term. But there was a big swimming championship coming up, before he left...

Swimming

The main thing for me was the swimming. The Fusiliers took it seriously. There was a good pool in the barracks, a German Flak barracks. Newer than ours, as they were part of Hitler's rearmament. The buildings still had German signs. "Haben Sie das Licht ausgeschaltet?" (Have you put the light out?). "Tur zu!" (Shut the door!).

There was a German swimming coach, Willi (Schultz I think), who was very good. The swimming team competed with other units, not only in the Division. We went to swim against the Belgian Division in their zone across the Rhine. I remember that was damn cold, but the Belgians were nice.

On 27th of March 1948, his diary says that he was swimming for the 1st Battalion, Royal Fusiliers. On Belgian National Day, at the end of the week in May when he got his Immediate Release form, he was swimming for 2 Div against the French and Belgians, at Ludenschied.

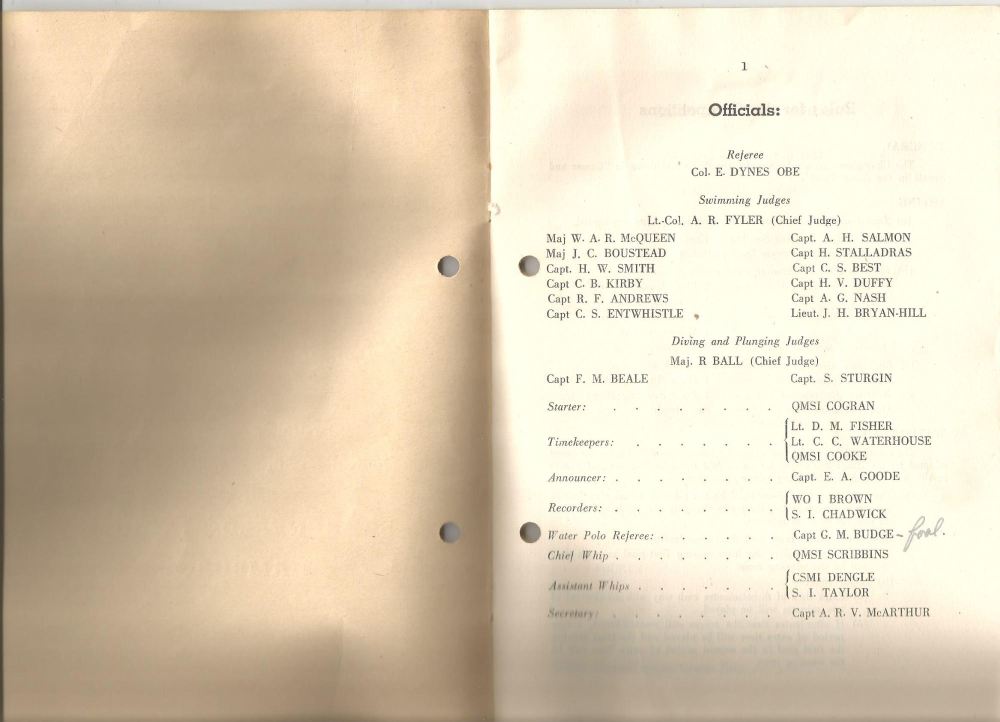

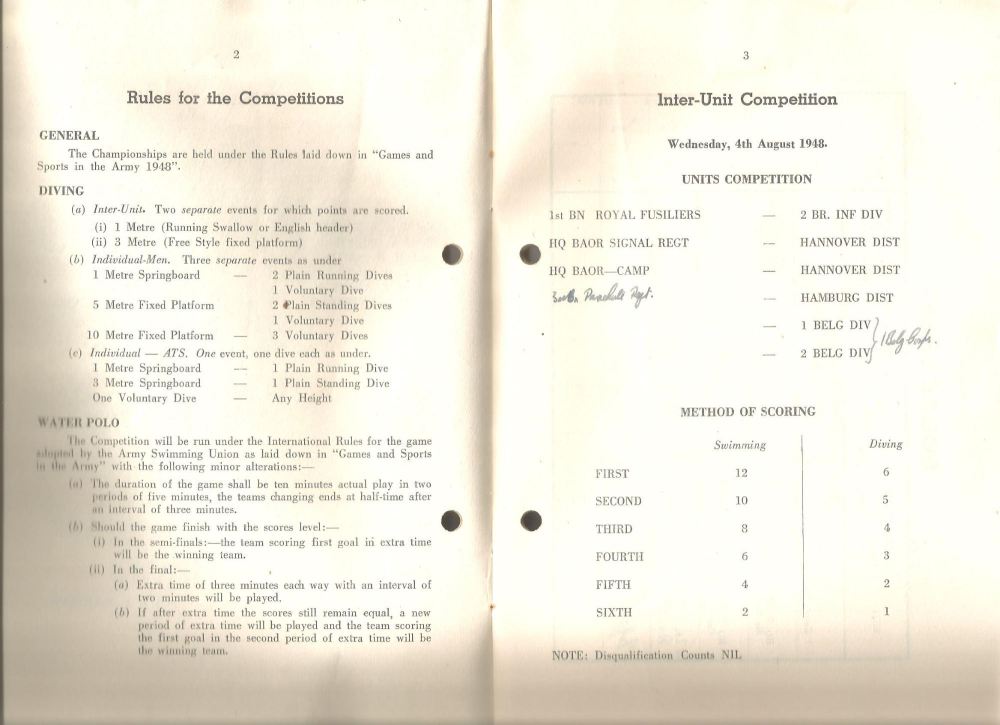

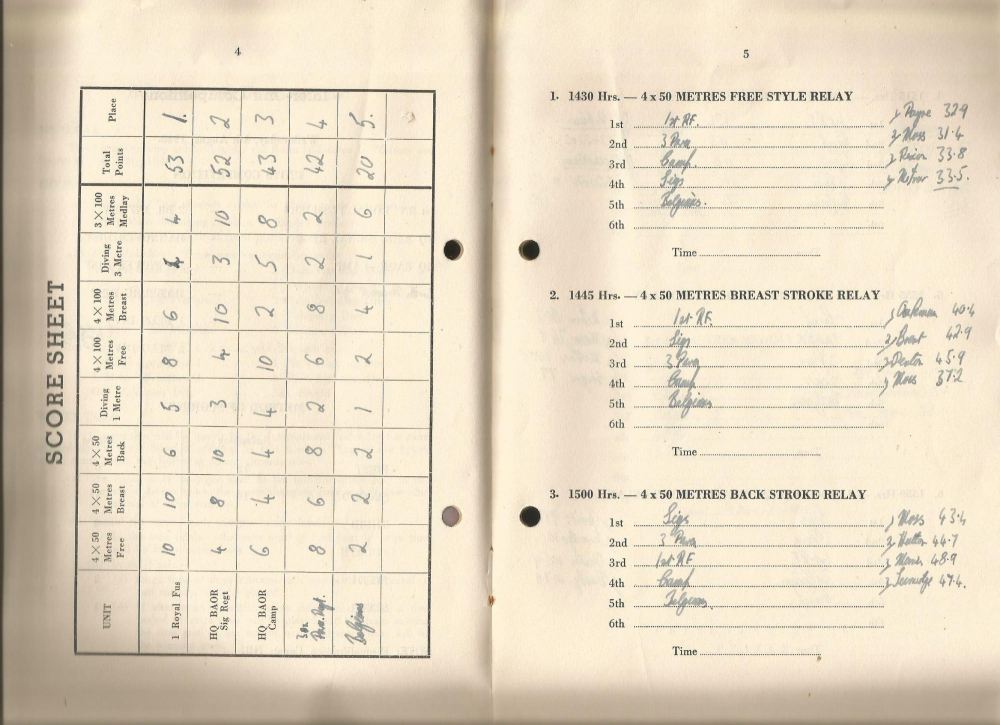

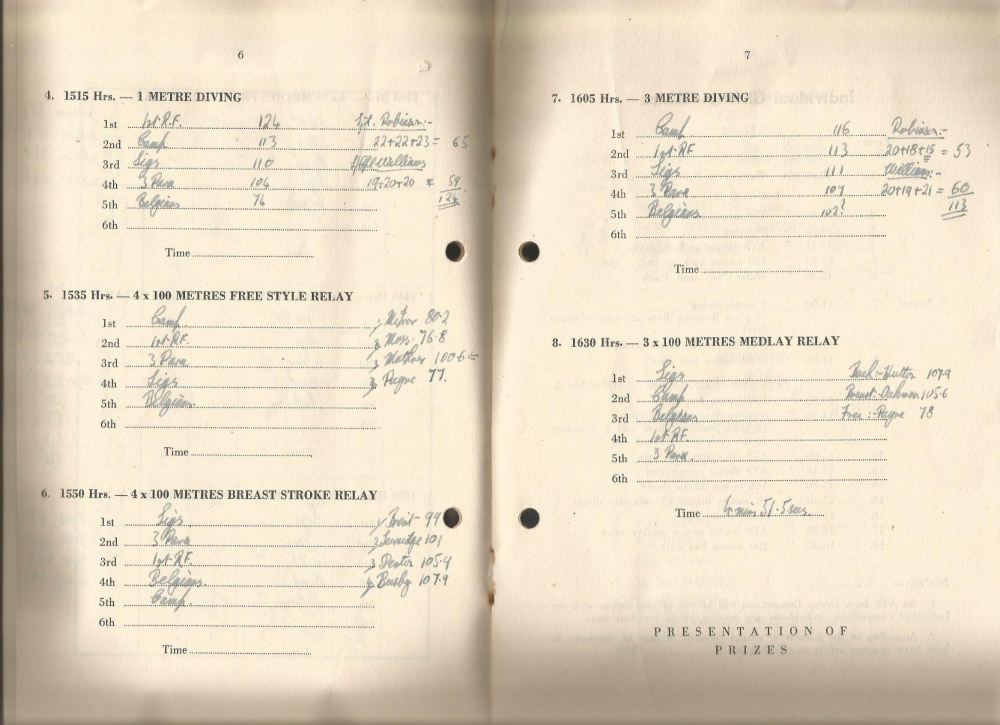

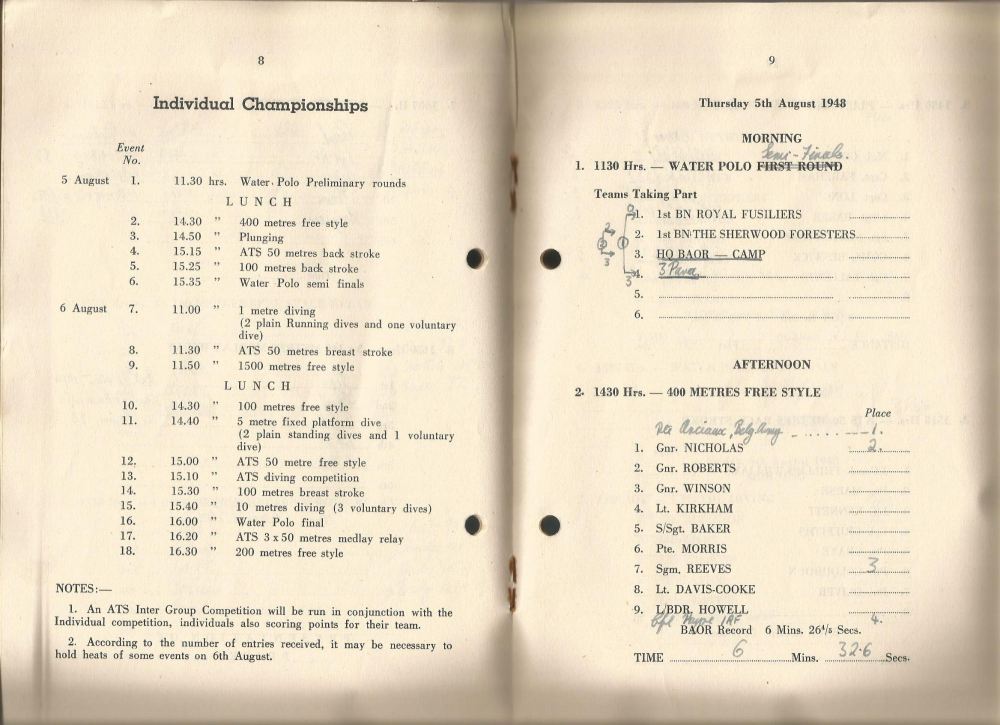

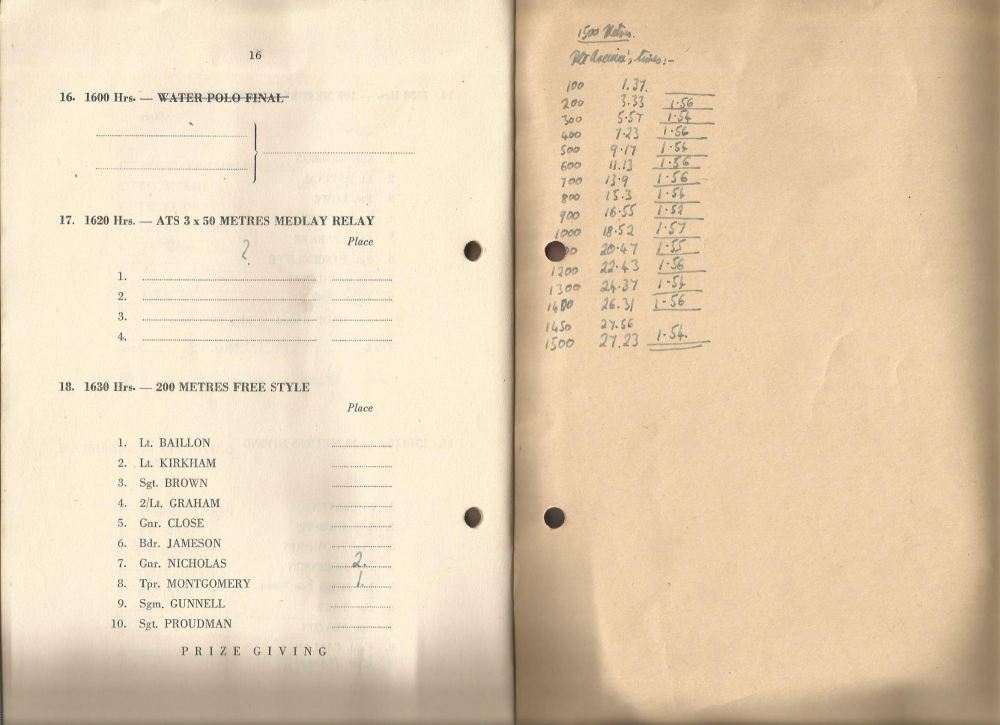

Rhine Army Inter-unit swimming championships

He left for Hamburg on the 3rd of August, for the four day long Inter-Unit Championships. Winners, he notes.

Eventually we got into the finals of the Rhine Army Championships, which was exciting for all of us in the team. Then my Class B release came through with orders to report somewhere. I decided I'd rather stay and swim than spend a couple of months in some holding camp. So I went to see the C.O. who agreed to see to a delay, and was highly congratulatory on my sense of duty to the regiment. "I wish some of my NCO's were like that". Well, it wasn't quite that. Still, I stayed and it was a great time. The finals were in the Olympic Pool at Hamburg on 4th, 5th and 6th August 1948. We only just won, from the Signals Regiment, from HQ BAOR, 53 to 52. They were a nice bunch, and I felt that morally they had won, as their team was about half the size of ours. I still have the little trophy.

Here below are some pictures of Fusileer Rixon, A Coy, Squad 2, First Bn Royal Fusileers, doing daring dives at Bahrenfeld Stadium, Hamburg, on the 5th of August 1948. These dives obviously impressed Geoff immensely. Note Union Jack flying. This was Allied Occupied Germany.

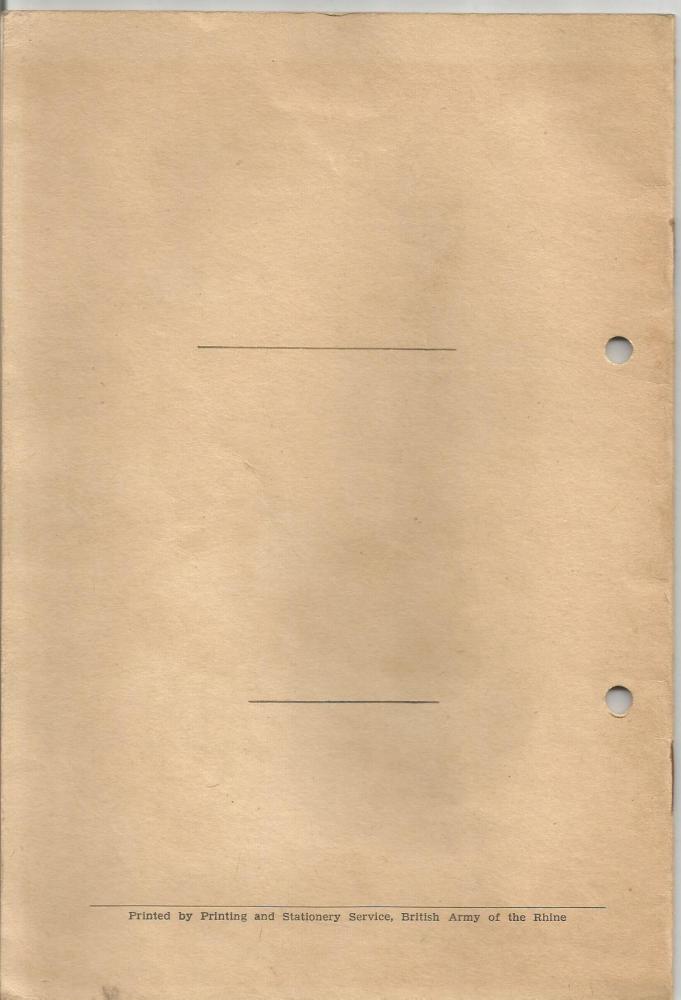

The Bahrenfeld Stadium, Hamburg the next day of the championship, 6th August 1948.

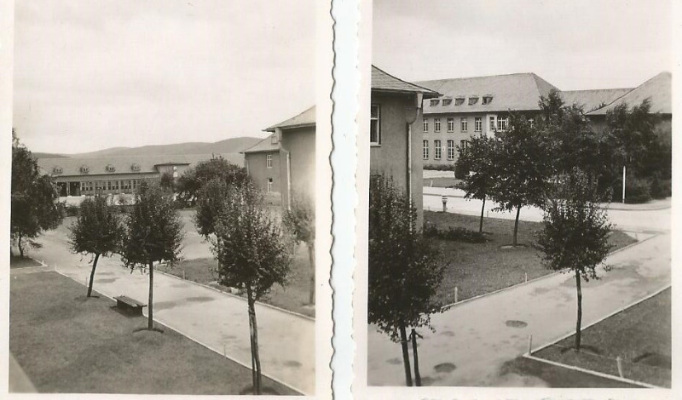

Aldershot Barracks, Iserlohn, 1948

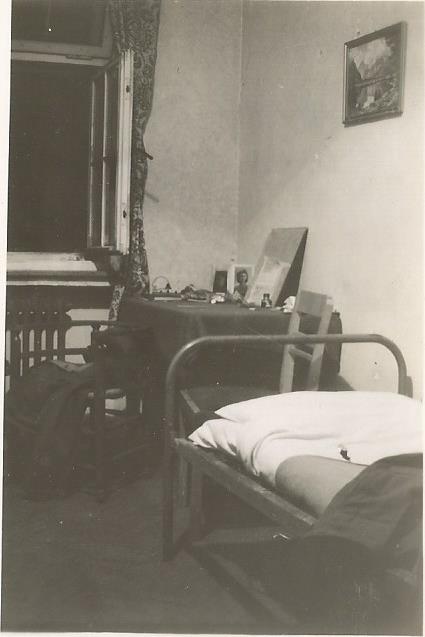

He took some pictures of the barracks, too. Here is the view, left and right, from his room at Aldershot Barracks, Iserlohn, 18th August 1948, just before he left.

and the inside of his room, n58, on the same day.

Demob

His diary has a count down, from '10' weeks on 9th July, to '1' in thick bold on 10th September.

When the time eventually came to leave, there was no transport available, cars or trucks. So I left in an AFV, armoured fighting vehicle, all the way to Hamm station. I had to make my way to Buchanan Castle, at Drymen, not far from Glasgow. There we were put up for a night, I think, then went through demob, a sort of reverse of signing on. Handing in the spare uniforms and equipment, and being fitted out with a demob suit. These were notorious for poor quality and bad fit. I chose the best I could, but I never wore it. I have an idea it went to one of Dad's workmen as a working suit.

He said that he was only accepted because he had been doing National Service and they made special dispensation for returning boys whose lives had been disrupted. His maths wasn't good enough and he had to take extra classes during the first year.

Civilian life, however, was not all good. His return and the start of university life were overshadowed by the death of his father from cancer almost as soon as he returned from Germany, in October 1948.