University College London 1948-51 | Tavistock Clinic and Insitutute 1951-9

Release

After being released from National Service, Geoff arrived back in the UK to study psychology at University College London in October 1948. His diary counts down the weeks to release, from '10' weeks on 9th July, to '1' in thick bold on 10th September. His diaries were lists of appointments, reminders and money calculations, not even noting major events like his father's death. But Saturday 11th September has 'Released' underlined twice. Sunday 26th September says 'Date of demand for Registration fee' and Sunday 2nd October 'Registration fee payable', with a tick. Monday 4th October, 'Term begins'.

Early Twenties- life after the army

This is the time of my early twenties. My father died soon after I returned home from the army and began College. A year later I married Jean. So for me, College was a daily journey up to London while I lived at home, first with both my parents, then my mother, then with Jean up in the front bedroom, which had been my parents', and the back room which was fixed up with sink and cooker by my brother.

Death of his father

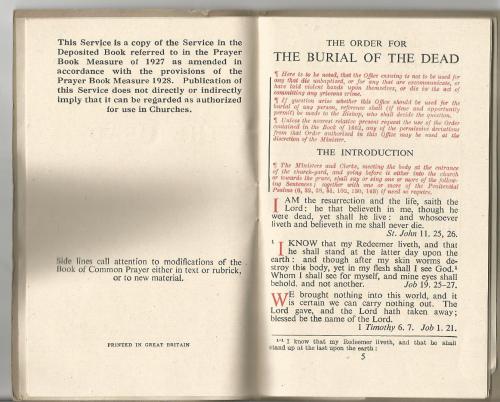

The order of service for my grandfather's funeral in October 1948. It goes on for over 20 pages.

Having just organized a completely tailor made funeral for Geoffrey, I was surprised to see how standardized this burial service was. And how long. No room for anything personal in those days.

I was able to go to university because I had my ex-serviceman's grant, called F.E.T.S. Further Education and Training Scheme. It had paid my fees and gave a living allowance, which was tight, but enough. When I got married, it went up, as there was a married allowance, paid even though Jean was earning. [Was she? ed]. I think the grant was £230. Bearing in mind that the average male wage couldn't have been more than about that, it wasn't bad. By today's standards, it was generous.

University College London

Why UCL? Probably because of meeting Raymond Winch. I had thought of Cambridge, though I fancied Oxford more, but when it came to the push I wasn't prepared to take up Latin again for the entrance requirements. There were Exhibition examinations which we could take, but I'm not sure if it was possible to get in on the Higher School results. Anyway UCL didn't require Latin for sciences, and I was very much taken with the idea of a secular college, founded albeit only in the 1840's, expressly for that reason. It was the first University College without a religious test of entry "that Godless College in Gower Street". It was strange, too, to see Jeremy Bentham himself, in his chair, in bis box. This is what he called his self-ikon- his mummified body, although the head was wax as the original went wrong.

The main building in Gower Street dates from the 1840's and is in the classical style, with a large columned portico approached by flight of steps. It faces the road across a large courtyard surrounded by connected buildings. The main gate has two little gatehouses, one of which was occupied by the Beadles on duty and the other by the college newspaper people. The main steps were a centre of activity and inactivity- a favourite loitering place and meeting place, used also for plays and singing.

The psychology department was in the main building, up a couple of floors, and consisted of one corridor, with a big lecture room-cum-lab, and a lot of other rooms for staff and meetings on either side. At the end it widened a bit, leaving a sort of common space, from which led the students' common room. This was used for some lectures too. It had a vast old table the size of a billiard table, with some old battered chairs and sofas around, some leather. There were notice boards, along the main corridor, or round the corner in the wide bit. The first notice which impressed me was the results of the intermediate exams at the end of my first year. I not only got a first, but came first. A performance never to be repeated, but at least it showed I liked the subject matter and at that stage it was not excessively demanding.

Pre-Asperger's Society

As for subject interest, I had by the time I left school, got to the point between physiology and philosophy. The choice of psychology wasn't a combination or compromise, but a refinement of the physiology interest. The thought that there was a subject which could explain about behaviour and feelings was appealing. I needed explanations about me, about my mother, about getting on with people, about what people felt about me, why I could and couldn't do different things, who I was and why. But I didn't make those connections at the time.

Many years later, it turned out that we have Asperger's syndrome in the family. Geoffrey clearly displayed the classic symptoms, but of course was completely unaware of this throughout his life. His interest in neurology and behaviour and differences, in a time when the knowledge of how mild autism sets us apart from the neurotypicals, was fascinating for its precision. He knew what, but not why. He was also an exceptional achiever for someone with Asperger's, although life was never easy for him.

UCL staff- The old stagers

Among the staff of the department were people whose names were in the literature, and had been around for a while. Cyril Burt was the professor, and head of department, Jack Flugel was a psycho-analyst and historian, and Philpott was an experimental and statistics man.

Cyril Burt

Near the end of my second year, when the Committee of the Psychological Society were fixing up his retirement dinner and presentation, he met me in the corridor. "Ah, you want to study psychology?" " Well, I've been here two years". He must have seen me around perhaps? Apart from such a lapse of memory, he seemed on the ball, and was a most entertaining lecturer. I was impressed with his work, which after all was founding father stuff as far as psychology and psychological services in this country were concerned. Professor Sir Cyril Burt. He discussed the 'body-mind problem' and the question of the genetic component in intelligence.

It was on the latter question that he was accused after his death of falsifying data, invented imaginary research assistants, and generally being a fraud and a liar. I, with other past students, was approached some years later by one Gillies of the Sunday Times, who was compiling the case against Burt. Had I ever known of two lady research assistants around the department? Well, I wasn't sure. I seem to remember a couple of women around, but I had forgotten who they were, and what they were doing. It's possible Burt did too. Hearnshaw published a biography which was clearly taken by press reviewers as cooking Burt's goose as a fraud and a charlatan. Another book was published by Joynson which repeatedly vindicates most of what he did. Recently, Arthur Summerfield and another, reviewed the evidence and concluded that some of the accusations were not proven, but much of Burt's evidence on twin studies was unreliable. Arthur was at college when I was, and eventually became Burt's successor in the chair of psychology.

Some of us at the time thought well enough of Burt. I was one of the group who arranged his retirement dinner and presentation. We collected enough to buy him a little calculating machine. In those days, there were half a dozen manual machines in the department, and a couple of electrical calculators, an American Marchant and a nice Swiss machine, Facit, or Ohdtner I think- I can remember its look and sound. Such machines were pricey, and we just managed a manual one. Handle on the right and lots of cogs. We had consulted Burt about it and he was very pleased to have it. I think it cost £120, the equivalent of half of my grant.

S.J.F. Philpott

Most people were known, as, for instance 'Cyril Burt' or 'Freddie Ayer'. Philpott was 'Philpott'. He taught elementary cognitive psychology, experimental psychology and statistics. Experimental psychology was then about perceptual thresholds discrimination, reaction times and PGR- psychogalvanic response. We did the little experiments in class. Quite fun, not vital stuff, perhaps. In the final examinations there was a laboratory session. My task was to determine if titles on a book spine were quicker to read downwards or upwards. Done with a tachistoscope- a primitve shutter arrangement like a guillotine which exposed the object briefy. Can't remember how I controlled for the effect of the shutter moving down, which would favour something written downwards, but I passed. The answer is downwards. Which also makes it possible to read the spine when the book is lying on its back.

Philpott taught stats too. Not very mathematically, though. The formula for rank order correlation had a 6 in it. Why? Well, he said, it makes the answer come out better. That is the Spearman correlation. He knew Spearman, who was dead by then. Spearman was head of department from 1907-1931. He invented factor analysis, and the idea of the general and special factors in intelligence.

J.C. Flugel

Jack Flugel's Hundred Years of Psychology was a popular and informative book. He knew Spearman when he was at UCL, of course. Mind you, there was a fifteen year gap. That gap was highly productive in psychology, pushed along, of course, by the war.

The introductory teaching of psychology still used the older distinction, now never heard, between cognitive and orectic. Cognitive pshcyology is going strong now. Perception, knowledge, thinking, remembering. Orectic is feeling, emotions, intentions and willing, otherwise known as affective (feeling) and cognitive (will). It's the term rather than the interest which has changed. There's plenty of interest in assertion, stress and suchlike fashions.

Jack Flugel taught orectic psychology, and later more specifically paycho-analytic theory. I wasn't that grabbed by it at the time, as it was taught as a history of ideas, and it was through other and later experiences that the connection with practice and experience was made. Still, to have a psycho-analyst in post and in a senior position was rare. Not that the others were ingenues. They were a mixed lot, but I think in retrospect that it was a good department, and a good degree. The whole place then was widely based, although a centre line as it were, was statistical and cognitive.

Roger Russell

In my last year, Roger Russell took over from Cyril Burt, and I had some contact with him in the immediately following years in postgraduate research seminars. Although I can't now recall the content, I remember them as interesting. He was a friendly man, though I don't know that he was very eminent as a theorist or researcher. He had been at Philadelphia University, and I think went on after a few years to be general secretary of the American Psychological Society.

We used to meet with him as the committee of the departmental society, talking about departmental affairs of some kind. I remember I invited him home one evening. He came all the way to Croydon, and I think a few other students were there too, Liz Palmer (became Newson) among others. I was living upstairs in the back room of Mum's house. Russell was introduced to Mum. After courtesies he commented on her television, which was in a big floor-standing cabinet. "Gee, that's the biggest TV I've ever seen".

There was one occasion in my last year when I was looking at the notice board for jobs. He passed and chatted. I recall I said it looked as if I would have to go either to the Maudsley and calculate or to the Tavi and intuit. He said it really was not as bad as all that. In the end I went to the Tavi where one of the first things I did was to calculate.

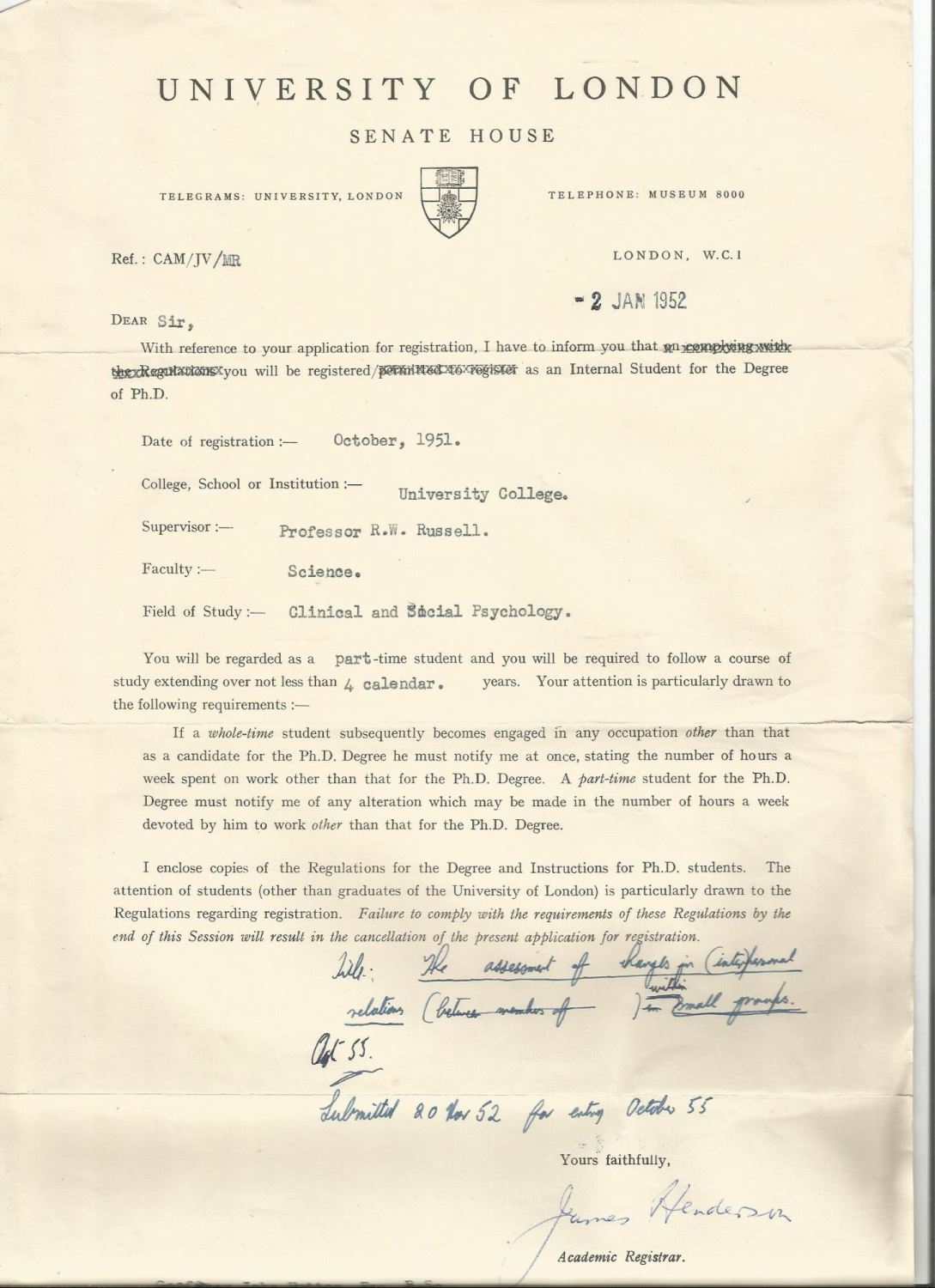

Cecily de Monchaux

Cecliy de Monchaux became my supervisor for Ph.D., which I never finished. Social psychology was her field, and she became an analyst, too. I had a lot of time for her. My topic was about groups. I think the title was something like 'the assessment of interpersonal relations in small groups.' I never got around to much on the topic for my Ph.D. When I was at the Tavi Institute and working on research at Acton Technical College, I set out to do things about that instead, and got something written. The Ph.D. finally faded when the course of the project I was working on and using for my subject, changed direction in some planning meeting we had with the Acton and Middlesex County people.

Freddie Ayer and C.E.M Joad

Freddie Ayer was in the philosophy department while I was there, at least at the beginning. I think he moved to Oxford while I was still there, but I can't remember the exact date. Anyway I met him, and he took some lectures. The first philosophy lectures that I'd taken were inter-collegiate, that is to say they were held in one of the other colleges of London University. They were taken by C.E.M. Joad at Birkbeck College.

It had so happened that in my time before the army when I was reading philosophy, I had read a lot from two of Joad's books, so I was interested to see him in action. In a big introductory lecture you can't expect much interaction, but he tried. After all he had been on the radio Brains Trust for years, with Julian Huxley and Commander Campbell. He was a clear lecturer on what is anyway pretty boring stuff. David Hume, Locke, Berkeley and so on. He would seek to use people in the audience as 'straight men' to offer the laymen's feed points. I got involved by not playing the role properly. It was something about intrinsic essences and qualities- Hume or Berkeley. The point was to think of an orange and remove the colour, then the taste, then the shape, the size and so on and see what was left as the essence. But I wouldn't take away the colour. I offered to substutute another colour, but it wouldn't then be an orange, but I refused to remove any qualities as it was meaningless. Philosophically it may have been right, but it rather spoilt the act.

Our later lectures in philosophy were taken by Stewart Hampshire. All very much more advanced and difficult thinking- Kant and his essences.

John Whitfield was the Reader in the department. He didn't do much if any lecturing and had overview of the calculators. He was interesting to talk to, and involved us from time to time in bits of experiments. It was from him that I got the idea that a Reader was the thing to be. It was sixteen years before I got a Readership, at Bath, but it wasn't the same by then.

The course

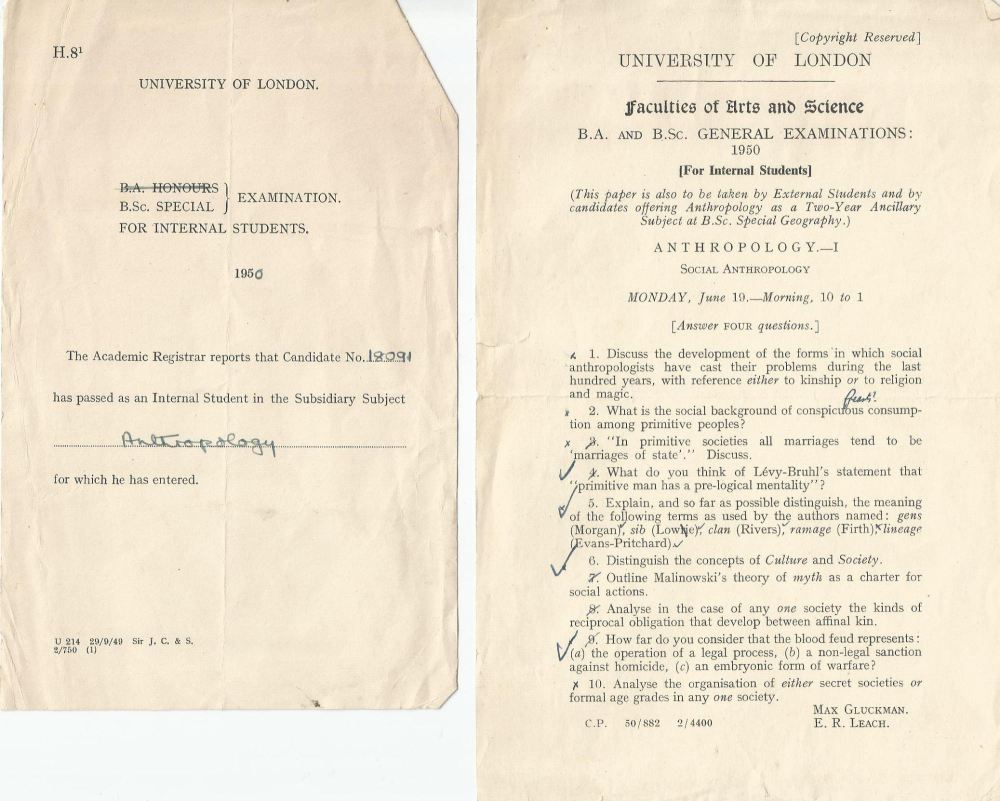

The degree as I and my contemporaries took it was widely based. The psychology itself included some physiology and philosophy, statistics and a bit of language- one question in finals was a passage in German and French, one of which you had to translate and comment upon. My subsidiary anthropology was itself pretty wide ranging.

Here is his Anthropology exam, part 1 of 3, from 1950. We have many exam papers, both in anthropology and psychology.

I had the choice of social anthropology (about societies, structure and culture) and either more ethnology (African mostly) or physical anthropology (evolution and racial differences- blood groups and Swanscombe man- "appears to be a simian jaw and a human skull" which of course it later proved to be.) I also took prehistoric archaeology and comparative linguistics. Marvellous general knowledge, and a very good basis for specialist psychology and particularly for the organizational work I later took up. One of my first year essays in social anthropology was on the relations between environment, technology, and social structure. I've been writing on it ever since.

One of the advantages of some of the subsidiaries was that class numbers were uneconomically small, so that we had to go to other colleges. The linguistics was in the School of Oriental and African Studies. That was fun, about phonetics and differences in accent and dialect, which interested me anyway. The archaeology was in the Institute of Archaeology in Regent's Park and was taken by Wiener, and Gordon Childe, both pretty distinguished. Wiener was younger and very clear and explanatory. Childe was an old stager who had been around since the early days of British archaeology. His lectures on paleolithic hand axes were a bit dry and dull. Fortunately he lectured in the dark and he showed slides. "This is, ah, a flake from an early Acheulian hand axe factory. Notice the impact plane." Thump of stick on floor "Next slide please".

One of the advanced physical anthropology seminars with Barnicott, had only about six of us. It was one of the most interesting events of my time there. One of the other students was Davida, an American lady, who later married Gurth Higgin. Another 'occasional' student taking this seminar out of interest was Constance Cummings, an American actress, who had played the wife in the film 'Constant Nymph' with Rex Harrison and Margaret Rutherford. On one of our trips to the zoo to see strange mammals and marsupials, we were taken behind the scenes to see a Tarsia. He was kept in the warm because he was a bit delicate. About the size of a hand, with very tiny hands, he was very important in evolutionary terms. As he was nocturnal he had great big eyes, which were fixed.

The Tarsia, queer little beast

Can't swivel his eyes in the least

But when sitting at rest

With his tum facing west

He can turn his head round to the East.

He could, too. The Bush Baby was a favourite, and we got to handle one. It peed on Constance's expensively clad arm. "oh the dear little thing", with such a look of distainful suffering in the cause of learning. She was nice, and though it caused a little amusement from time to time, her naive questions did advance the discussion. Once on the question of essential human characteristics, she had asked something rather funny about ape behaviour. I wish I could remember the question, but the answer was to the effect that "if we were in the jungle, to come to a clearing in which an ape was sitting in front of his hut playing the violin, we might have some cause to suspect that it might not be an ape, but a man".

Some of the classes and lectures were intellectually or academically demanding. Some were less so, but interestingly relevant to everyday life. The lectures we had at Birkbeck with Professor Mace were such. He lectured on child development, and it all seemed to be based less on theory and more on experience and wisdom. I liked his phases of development, which included the 'primitive man stage' 8-11, very apt, but hardly sound theory, I thought.

Social life at UCL

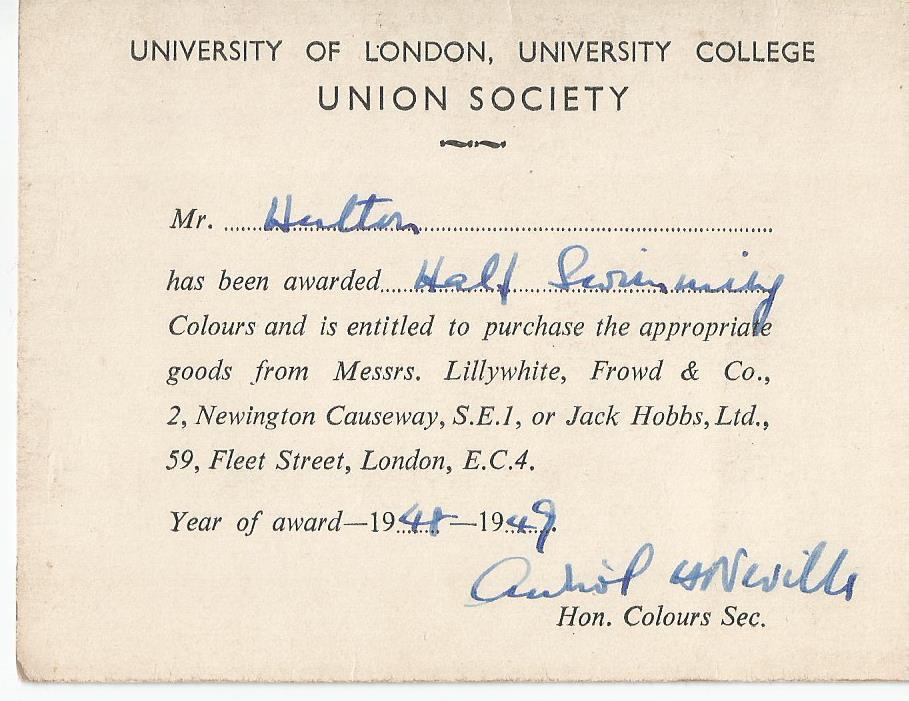

The extra-curricular activities at college were most important to me. I started off with swimming, following directly on from my army involvment with it. For the first winter I assiduously went at lunch times down Gower Street to the YWCA, yes W, where they had a swimming pool, and a canteen. I swam in a couple of matches, and was given a half blue. Then I stopped.

His diary shows that attended other swimming matches as a supporter, 'Women's swimming at King's', for example, on 2nd December and his own 'Swimming at King's' on 6th and 8th.

I joined the Labour Club almost atraight away, and was also active in Croydon. I don't remember the exact parallel of events, but in Croydon I got on the ward committee. The secretary was Reg Prentice, who was at LSE, I think. In the UCL Labour Party club I got to be chairman while Bernard Crick (who had been to Whitgift School in Croydon) was secretary. Reg became an M.P. but changed parties. Bernard became a professor of politics.

As a member of the Labour Party, Geoff was involved as a student in the campaign for the 1949 election. His diary says the Campaign began on Tuesday 19th February and polling day was the 12th of May, when he went around 'knocking -up' that is, reminding older people about the vote and escorting them if they needed help to the polling station.

Politics were an active and vital interest and generated a lot of excitiment at election time. Results came out on the wireless, and on frequent editions of the evening papers. Gathering outside lectures in the corridor, in passages and quads, passing on the latest, and cheering and sulking.

We used to have people to address meetings, and I had a lot of contacting to arrange the dates. Fenner Brockway, Hartley Shawcross, Ian Mikardo and such. Politics in Parliament was fierce then. Just recently (this was written in 1990) with the poll tax protests, the atmosphere has moved a little in the direction of what it was like in the late 1940's.

The Labour programme was about the declared values of fair shares and equal opportunity, and its economic king pin was nationalization, which was fought tooth and nail by the Tories. The arguments were about the failure of private capital, (true), the need to own the 'commanding heights of the economy' as Nye Bevan put it; and on the other side about how the civil service bureaucracy can't run industry (true), and the dead hand of the state. The Tories then were as keen on private capital and 'free enterprise' as antagonistic to the unions as the Thatcherites now. But there was a respect for the constitution and an acceptance of the Beveridge kind of social justice and state action for welfare.

Jean

In his diary there was a 'Going Down Dance' for the end of term, at St Pancras Town Hall, on 23rd June 1949. I wonder if his fiancee Jean went. There is only one mention of meeting her in his diary, maybe because they met frequently and it wasn't an 'event'. I do wonder if she participated in the university social life, as she was not a part of that lifestyle. The one mention, was 'Jean to 25, parents away' on Wednedsay 10th of July 1949. '25' was his house, so was that was his parents away, her parents, or both? Anyway, she stayed with him until the 24th. In August, he went to Wales on holiday for two weeks. Not sure who with.

A brief mention in his diary of their wedding, after the end of term in December 1949. 'Wedding if can't get week away' it says, on 17th of December. Their wedding was the 16th! 'Leave Croydon', also on 17th. 'Arrive Scilly' 18th. We had no idea he had ever been to the Scilly Isles. We have no pictures of his wedding, and his life with Jean was never talked about after he met my mother, sadly.

Life must have been very difficult for Jean. She had been a nurse. She had a career, income, independence in the war and her own life. It is unclear whether she gave up work when she was married, as was the norm. The young couple lived in two rooms upstairs at his parents house, with his widowed mother. Geoff was out at University in the day and at society meetings at night, especially for the music, which continued long after he left university. Not much of a life for Jean, but Geoff thrived.

Music

One lunch time I heard a recital by the college madrigal group, and thought they were damn good. Liz Palmer (Newson), a fellow psychology student, encouraged me to in for an audition. That's how I first met Tony Addison, and got into College music. It picked up an interest from the time at school, and became a predominant interest for me for some years after I finished my degree, through the College, and subsequently through Tony Benskin, my singing teacher and the Dorian Singers.

There was an audition for the madrigal group. It was an Italian ballet 'Matona, mia cara". A ballet has verses and a nonsense refrain like fallala or in this case diridondon. I never have sight-read well, and I must have made a balls of it, but perhaps Anthony was short of people. (Dad modestly does not mention his excellent bass voice). Anyway it was fun singing and taking part in the odd recital at College, some outdoors and on the steps.

That was in my first year. I sang in the main choir too, which took part in college concerts- Britten's 'Ode to St Cecilia' was the first one I took part in. Jeff Taylor sang solos, so did Mary Illing. Jeff was studying geography, and also a footballer, centre-forward for Chelsea, and later Fulham, or vice versa, it was up not down, anyway. He became a profesional baritone, as Neilson Taylor.

It was in my third year, 1951, that we began the Opera Group and put on the first opera. It was the initiative of Tony Addison. The first performances were of Mozart "Bastien and Bastienne" and Purcell "Dido and Aeneas". I remember Roger Russell wondering if it could be managed as well as finals.

Talking of finals, I had revised quite hard with Len Jones and I recall stopping some time before the exams. The idea was to try and relax and go into the exam fresher. University examinations were held in South Kensington at the university examination halls. Thousands of students, lots of big halls, lots of desks. Very intimidating. I got an upper second, was fourth in psychology and eighth in the whole university. Len Jones went on to Bart's to study medicine, and then died.

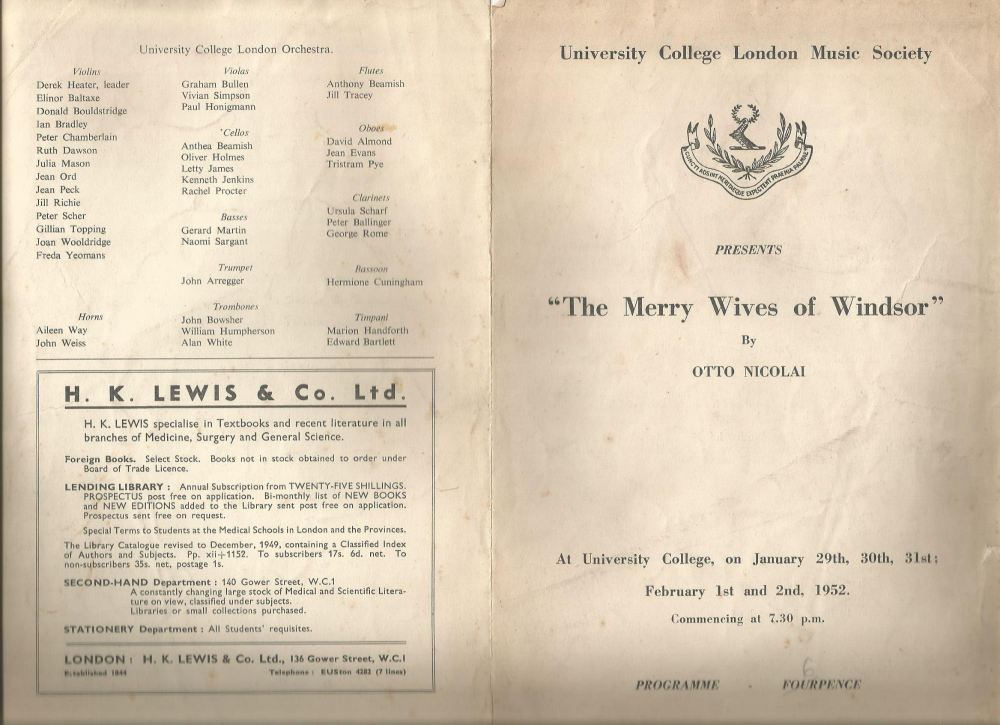

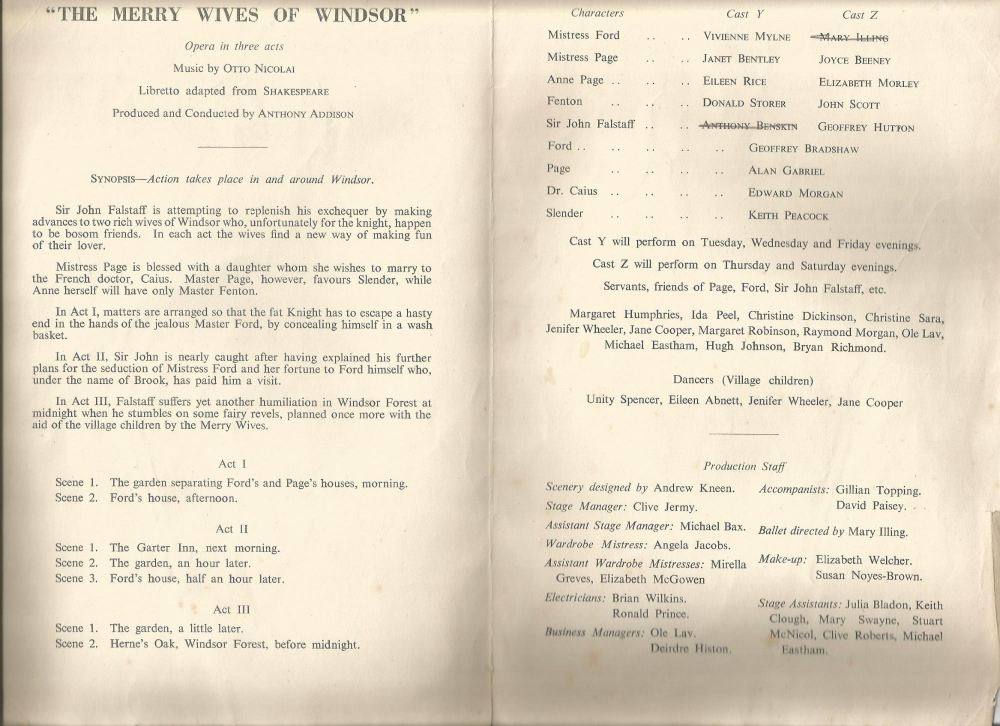

The opera was enormous fun. Mary Illing was Bastienne to my Colas, but I can't remember the name of the tenor who played Bastien. Dido was Vivienne Mylne and Aeneas was Ian Round. It was the beginning of a series in which I took part over the next four years- Falstaff in Nicholai's 'Merry Wives of Windsor' in 1952, then a gap of a year before Donizetti's 'l'Elizir d'Amore' in 1954 and finishing with Bizet's 'Don Procopio' in 1955.

Here is the programme for their 1952 performance of the 'Merry Wives of Windsor'. I have a fine picture by Denis de Marney of Geoff as Falstaff, but I think it is still copyright, so I am not showing it here. Some of the names on the programme were familiar as family friends throughout my life.

I met Gill Topping, both through the operatic activities in which she accompanied rehearsals, and in the psychology department which she had joined in my third year, I think, after leaving the Royal College of Music. I believe we met through Len Jones, with whom she had taken up.

Geoffrey and Gill remained lifelong good friends and saw each other annually with their families and later afterwards in older age. Geoffrey visited her in the last week of her life, in December 1992 at Sherborne.

...and meanwhile, on to the Tavistock Clinic

In 1951, after graduation, I joined the Tavistock Clinic for two years training in clinical psychology. The interview was with Herbert Phillipson, the chief Medical Director and Jock Sutherland. Jock said they had hardly any rooms, but perhaps they could find a cupboard.

The appointment, as an Assistant Clinical Psychologist, was for two years, the first to be spent in the department of Children and Parents and the second in the Adult department. In the children's department I joined the group which was training in educational psychology, and the group training in psychiatric social work. We all shared some series of talks from senior staff, although much of the work of the psychologists and social workers was separate. I got to take diagnostic cases- testing children's intelligence and taking projective testing, namely the Rorscharch and Object Relations Technique which had been developed by Herbert Phillipson. I also got to take a case of remedial teaching, and a social case as a social worker.

I learned very fast and liked it a lot of it. I really don't think I managed to teach little Jimmy to read very well, and I don't really know how much the lady I was trying to help got from it. She was the parent of a child in treatment and I got to see the father too, sometimes.

Much of what I learned stayed with me and became part of my whole professional approach. This applied not only to the year in the Children's department, but even more to the Adult, and of course my six yers following that at the Tavistock Institute. The events which impressed me most in the Children's were the talks by John Bowlby on child development, the group therapy sessions with Jock Sutherland, and the personal relations with a lot of people, especially the Poppers, Jana and Erwin. He was a psychiatrist, she the chief psychologist in the Children's department and thus my main mentor.

John Bowlby's approach was not only clear and well founded intellectually, but felt so sensible and right. He placed emphasis on the feelings of the parents rather than rules, books and theories. The Poppers were Czech, from Prague, and were interested in music. In the first year, I was still singing opera at UCL. It was the year of Falstaff, and they were interested. In lunchtime discussions on music, they told me they went to the first performance of Rosenkavalier, going from Prague to Dresden for the event, in 1911.

and Opera with UCL continued...

L'Elisir d' Amore, 1954. Geoff, raising his hat in the centre.

Tony Addison was around for most of the time I was singing at UCL, conducting and generally directing. For one of the operas, 'Don Procopio', we had coaching from Marcus Dodds, who was then a repetiteur at Sadler's Wells Opera, while it was still at Sadlers' Wells and not yet Royal Opera. I got to go to Sadlers' Wells Theatre for one or two coaching sessions.

Don Procopio, 1955, with Geoff in the title role. There is another lovely still of this production below.

Dad told me on his 85th birthday about how much he had enjoyed his many friendships in those days and how different it was to his life aged 85. He said that they once went on a music weekend and sang operas, at a country house in the Downs belonging to a man who went on to direct the San Fransisco or Chicago orchestra. Dad had dementia by this stage but he could remember all of the names. It is my memory of the details that is the vague part. He said he had many good friendships and was sad it was all so long ago. He clearly also went away on music camps as we have the pictures...

Music Camp, I know not when or where. Geoff is the one with a moustache, middle right, having grown it after his father died. Good friend Gill is in the spotty skirt front row. Jean is in the front row, in the dark twinset.

Although Jean sometimes went too, she was reportedly rather out of place in the musical, very 'single' student atmosphere. The book 'Lucky Jim' always makes me think of this sort of thing. For Geoff, I think this was the best time of his life. He had affairs, more than one, I think. He had just got back from 2 years in the male environment of the army, had married his first girlfriend very young, having had no other sexual experience beforehand and was now surrounded by attractive single, intellectual women in the relaxed environment of 1950's academia. Not much of a life for Jean, as I say.

Anthony Benskin was acting as singing coach and was going to take the odd part. He was due to split the Falstaff role with me, but in the end I did the whole week, with both casts. That was quite interesting, singing with a different set of principals, though the chorus was constant. There were two casts for Donizetti, but I did Don Procopio.

After Falstaff, I took a year off, thinking it was at an end, and started singing lessons with Tony Benskin. They were mostly in the Dynley studios, opposite the Royal Academy in Euston Road, and quite convenient for the Tavi. Jeff Taylor had gone into the Royal Academy of Music. I kept up with Tony Benskin for some years after going to Edinburgh, and in Bath. Jean and I had gone to his wedding in about 1957 or 1958. He was interested in high fidelity, and had all sorts of bits of equipment in his rambling house in Beckington.

There was a period when I was just having singing lessons, and Tony took my voice back to basics, as it were, almost rebuilding it more properly. I sang lieder and operatic arias and went to informal singings. I used to go to Gill's in the early evening in Primrose Hill, to sing and such. It was on the improved, enriched and freer voice that I got into the Dorian singers a few years later. Must have been about 1956 or 1957, as I left for a reserach post at Edinburgh University in 1959. [We still have some taped recordings from Radio 3 broadcasts of the Dorians with Geoff singing].

Before I left, Anthony Addison offered me a job in the chorus of the Carl Rosa, with occasional walk-on minor parts. I think it was at £400 a year, which was less than I was getting at the Tavi, even after paying for psycho-analysis at £300 odd a year. So I couldn't afford it without giving up the analysis, which I was not prepared to do then. Makes one wonder, though, looking back on such turning points what life would have been like if it had gone the other way. I wouldn't have met Eileen, and there would have been no Alice, Nicholas and Lucy- the people I love most in the world.

Postscripts

There was in 1972 a 21st birthday party of the opera society. We originals were invited, and Eileen and I met Mary Illing, Jeff Taylor and others. Gill was there of course. Jeff Taylor came to see us some time later when he was visiting Bristol for a BBC concert. He had by then separated from his wife, whom he had married while we were still meeting in informal music evenings- Biddy I think she was.

Last Christmas, (1989), on the card from Vivienne Mylne, she wrote that she had been to Texas to lecture and had come across Anthony Addison, still doing operatic things.

Postscript- Vivienne Mylne died in June 1992 and Gill in December 1992. I went to a centenary day of the Psychology department on 18th October 1997, met some of my fellow students and Roger Russell, then 82.